Secret agents “El Pintor” and “Oficial Renco” unmask “ideological falsity” and destablization plot, so they say

by Eric Jackson

The Panama News is generally not in the habit of publishing politicians’ allegations about eavesdropping conspiracies or plots to destabilize the country. Such accusations are almost always the cheap coin of petty demagogues, and filler for daily newspapers at times when there’s not a lot of real news to publish. They are the moral equivalent of kids in a large family whining “he’s making faces at me” during a long drive in the station wagon, an offense that’s likely to get both the accuser and the accused slapped. This stuff is, from the news judgment point of view, highly unreliable.

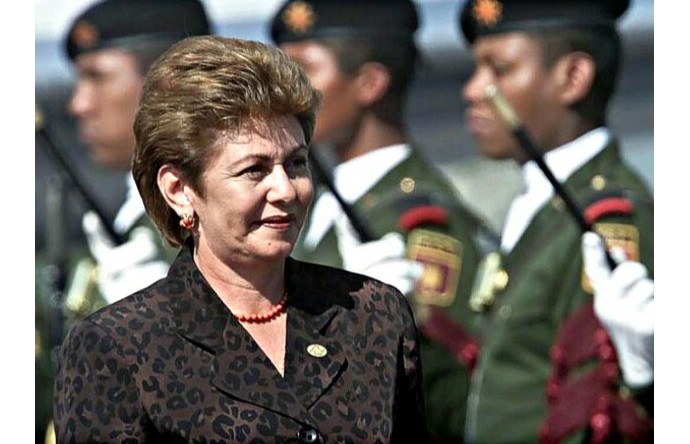

Ah, but Panama’s holiday season is upon us, the rains are at their annual height, kids of all ages who should be sent outdoors to play are staying inside and getting cranky, the legislators don’t have circuit funds to spread around, the president controls all three branches of the national government but is detested by the greater part of the country’s population — including an important part of her own party — and our economy may have bottomed out but we haven’t seen much of a rebound. And thus, against all odds and flying in the face of common sense, a weird little wiretapping allegation has captured the public imagination and provoked the Moscoso administration into inflicting substantial wounds upon itself.

It started out on November 11, with a fax arriving at Panama’s TV stations and the offices of various activists. This document, purporting to be on government stationery and bearing what looked like the signature of Minister of the Presidency Ivonne Young, included a list of 117 individuals whose phone calls were to be considered for interception. As received, the faxes contained a line indicating the phone number of origin, apparently that of an auto shop.

Of course, anyone with a computer with a scanner and an original or clean copy of one of the minister’s memos could have easily falsified the memo. Anyone with a semi-decent or better fax machine and a little bit of knowledge of how to program it could have easily falsified that data about the origin of those faxes.

“Ah,” one might say, “but phone company records surely wouldn’t lie.” But those could also be falsified, and notice that Minister of the Presidency Ivonne Young and National Security Council member and Economy and Finance Minister Norberto Delgado are among the Arnulfista bigwigs who sit on the board of directors of Cable & Wireless.

Ordinarily, one would have expected the matter to end with Ivonne Young’s statement that the document is a ridiculous fake, and next question, please. But no, she was out of the country, despite modern telecommunications supposedly “unavailable,” with nothing to say for 10 days.

But other Moscoso administration figures, whose “knowledge” would be hearsay at best, were quick to deny and cry foul.

And meanwhile, the cast of 117 supposed wiretap targets raised some eyebrows, because this wasn’t a mere collection of partisan foes and nosy reporters. It included Moscoso appointees to the Supreme Court and other prominent Arnulfistas thought to be friends of the president. It included some men whom the gossip mills had at one time or another identified as significant in Mireya’s life. Key national business leaders, and owners of (rather than reporters for) the mainstream media appeared. But of course, the leading lights of the opposition PRD and Christian Democrats, and former Moscoso advisors turned critics also made the list. The commie radicals who like to block the streets and talk about revolution didn’t make the list, and neither did the leaders of local protests that have at various times during the Moscoso administration paralyzed Colon, Bocas del Toro and Baru. No bus riders here — this was the BMW set.

Were the list genuine, it would be evidence of a terrible paranoia gripping the presidency.

But it looked fishy on its face, and had Ivonne Young placed a few timely calls to the effect that “You interrupted my vacation for THIS?” and top Moscoso administration figures countered reporters’ questions with queries of their own, like about whether the journalists had heard disembodied voices or seen unidentified flying objects, the story probably would have died.

But no such luck. President Moscoso cancelled her plans to attend a summit of Ibero-American heads of state in Santo Domingo, citing the wiretap allegations as the reason. She said that suspects had been identified, and would feel the full weight of the law. But she didn’t say anything specific at first, which left a few days for the daily newspapers and the broadcast media to gossip and speculate.

The articles and conversations turned to the ease with which electronic communications can be intercepted these days. (No pity for the poor cops who would have to listen to all this and sort through it in search of sinister meaning was expressed — it is one indication of Panama’s underdevelopment that the news media fix their starry-eyed attention on powerful imported technologies and ignore the mundane but very real human limitations on the use of such widgets from the industrialized world.) El Panama America ran a series of articles on various wiretapping techniques, all of which are obsolete compared to the FBI’s Carnivore and the US Navy’s Echelon systems.

While the nation waited for Mireya to show her cards, public discourse turned to past wiretap allegations and drew new life. Did Guillermo Endara throw the Christian Democrats out of his administration in 1991 because former Vice-president and Government and Justice Minister Ricardo Arias Calderón had set up a wiretap operation within the former US military base at Quarry Heights? (Endara hinted yes, Arias Calderón vehemently denied.) Who made those cell phone tapes of the high and mighty that so titillated voyeurs earlier in the Moscoso administration? Did Mireya herself order eavesdropping aimed at a former boyfriend?

(Oddly missing from the discussion was the case of former Supreme Court magistrate José Manuel Faúndes, who was caught on two taped phone calls very clearly negotiating with lawyers about cases before the courts, without the opposing counsel participating in the conversations, with the apparent subject of those conversations the size of the bribes necessary to obtain the release of drug traffickers. We know that the second tape was made by police pursuant to a warrant signed by legislator Miguel Bush, who was at the time head of the assembly’s drugs committee. The provenance of the first tape has never been revealed, but most observers guess that it came from the United States government via the DEA, having been intercepted by the US Navy’s Echelon electronic surveillance system or some similar technology. A majority of legislators voted to impeach Faúndes, but not enough to convict him. Reopening this can of worms would be most inconvenient for the partisan-aligned Panamanian mainstream media — the Arnulfistas and their allies put their stamp of approval on hardcore corruption in the Supreme Court, and the PRD and their allies were parties to questionable and still not fully explained eavesdropping practices in their own right — so this matter was not discussed.)

Next, the Moscoso crowd let it leak, via Arnulfista legislator Francisco Alemán, that former Panama Defense Forces Major Aristides Valdonedo had something to do with the fabrication of the faxed purported memo. Alemán offered no evidence. Valdonedo vehemently denied it, and it was his denial rather than Alemán’s allegation that got the screaming headline in La Prensa.

Then, on November 18, the shoe figuratively dropped. It had been figuratively torn off, in the process of the Moscoso administration figuratively shooting itself in the foot.

At a solemn press conference, the assembled members of the National Security Council accused retiree and anti-corruption activist Enrique Montenegro Diviazo of fabricating the memo that bore Ivonne Young’s signature. Displaying a strange flow chart, they alleged a plot to destabilize Panama. The council members — Government and Justice Minister Arnulfo Escalona, National Police Chief Carlos Barés, National Security Council Secretary General Ramiro Jarvis and Economy and Finance Minister Norberto Delgado — said that their accusation was based on the data obtained from the faxes sent to television stations, the allegedly bogus wiretap memo had been sent from a telephone at either a Via Argentina car painting business or an adjacent body shop Grupo Style or Body Color, with which prime suspect Enrique Montenegro Diviazo’s son, Enrique Montenegro Paredes, they claimed is associated.

To back their claims, the National Security Council produced surveillance photos, most of which showed nothing that could be readily discerned, but one of which showed the elder Montenegro in front of Body Color on November 8. As in, the Moscoso administration was vehemently denying that it taps its critics’ phones, and as “proof” of this, it admitted that it had undercover agents following its critics around.

To bolster its case before an incredulous press corps, the National Security Council gave El Panama America access to several documents, including an “Apprecition of the National Situation and Plan of Action” attributed to Montenegro Diviazo, and logs of surveillance of the activist by agents code-named “El Pintor” and “Oficial Renzo.” By the admission of the National Security Council, the surveillance of Montenegro Diviazo had been going on since this past April.

At the press conference, Escalona said that criminal charges of “ideological falsity” had been filed against Montenegro Diviazo and other unspecified individuals. The government and justice minister cited several sections of the criminal code that have to do with defamation, economic sabotage and the falsification of documents. “Ideological falsity” is Escalona’s maladroit political usage rather than a commonly accepted legal term.

The Moscoso administration’s press conference did not rally the nation into a common front against those accused of plotting to destabilize Panama. The TV stations carried Montenegro Diviazo’s immediate denial, coupled with charges that the government itself had falsified Cable & Wireless records to frame him. The media’s “person in the street” interviews found that while Montenegro was not being hailed as a national hero, almost nobody believed the government’s allegations and almost everybody believed that whether or not the document in question was genuine, the government does tap phones.

The government’s credibility eroded as its own allegations were published in greater detail. The purported “action plan” to destabilize Panama, for example, did not include the detonation of bombs, intervention by foreign governments, sabotage against the canal or the banking system, rioting in the streets or the dumping of LSD into the water supply. The gist of the plot uncovered by secret agents “El Pintor” and “Oficial Renco” and released by Arnulfo Escalona et al, according to the document given to El Panama America, was both tame and laughable.

“So far all of the actions we have taken have had the hoped-for result,” the purported analysis and action plan stated. “An environment of instability and incredulity with regard to institutions has been created, which has caused a low level of popular support for the government and in a certain way created an internal division within the Arnulfista Party.” Looking forward, the document said that “for the moment the same rhythm of blows in the mass communications media must be maintained as our principal method to conserve the level of popular discredit and political rejection” of the government.

The supposed plan’s end game? To break up the governing alliance and defeat Mireya Moscoso’s faction in the 2004 elections. That is, what every opposition is supposed to try to do.

The government’s criminal complaint was duly filed with the Public Ministry and prosecutors and the Judicial Technical Police (PTJ) swung into action. They raided the auto repair and painting businesses in question, carrying away a fax machine for the TV crews. They announced that arrests had been ordered.

And meanwhile, not far down the street, Montenegro Diviazo held court at the El Prado restaurant, waiting for the PTJ to come take him away. Around the table with him were former President Guillermo Endara, former Panama City Mayor Mayín Correa and several former government ministers. The cops didn’t come that day.

That night at a campaign event one of the two presidential frontrunners according to the latest polls, Alberto Vallarino, made his appearance with alleged co-conspirator Valdonedo, declaring the former army intelligence officer a friend and rejecting the government’s alleged destabilization plot as “unsubstantiated.” Vallarino ran for president against Moscoso as a third-party candidate in 1999 and wants to be the Arnulfista Party’s standard-bearer in 2004, but so far Mireya has not allowed him to rejoin the party.

Reporters tracked down alleged minor players in the purported conspiracy. The owners of Grupo Style and Body Color denied that the two businesses were the same, that the younger Montenegro works for or owns either one, that the phone line over which the offending faxes were allegedly sent ever actually had a fax machine attached to it, and that they had any knowledge of or participated in any destabilization plot.

With the exception of the more or less moribund La Estrella, which is owned by Moscoso advisor “Onassis” García, the cartoonists, columnists and editorial writers at the nation’s daily newspapers produced a steady stream of scorn for and ridicule of the National Security Council’s allegations. One El Panama America’s front-page editorial called the whole affair a distraction from serious national economic problems, and another concluded that neither the wiretap memo nor the National Security Council’s charges were credible. La Prensa cartoonist Víctor Ramos portrayed National Police Chief Barés and National Security Director Jarvis, sweaty and frightened with guns drawn, hiding behind a wall from a fax machine printing out an image of a pistol, with Jarvis shouting “Watch out, it’s armed!” Boxing show host Juan Carlos Tapia, whose political commentaries enjoy a significant public following, dismissed Montenegro Diviazo as totally unreliable but concluded that the whole affair has reduced the Moscoso administration’s public credibility to zero.

Finally, on November 21 Ivonne Young returned to Panama and told reporters that the memo attributed to her was false. By then, nobody would argue to the contrary with her.

The truth about the purported wiretap memo had come to rest beside the point of the whole affair by the time that Young returned. What really matters is that, prompted by what appears to be a silly bit of nonsense, the Moscoso administration has inflicted grave injuries upon itself and doesn’t seem to understand what has happened.

Contact us by email at fund4thepanamanews@gmail.com

To fend off hackers, organized trolls and other online vandalism, our website comments feature is switched off. Instead, come to our Facebook page to join in the discussion.

These links are interactive — click on the boxes