From the archives:

US military activity in Panama (2010):

Drones, bases and the Tropical Test Center

Antiwar activist John Lindsay-Poland tracks down US military activity in Panama via ads and budget reports

by Eric Jackson

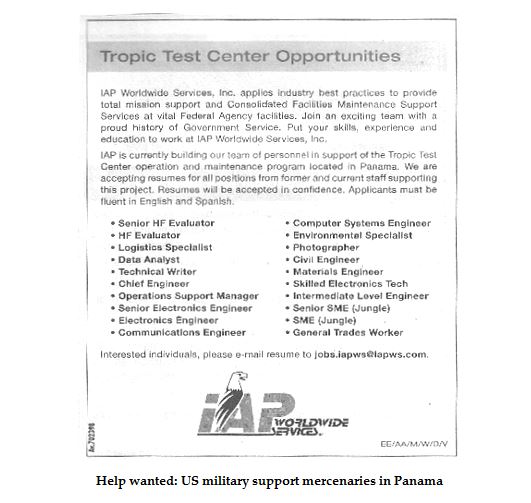

Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez

The Colombian Supreme Court struck down the agreement that would have allowed US military operations out of bases in Colombia, but the US military and US “civilian contractors” — the favored euphemism for mercenaries these days — have been busily setting up “aeronaval bases” here, according to the Martinelli administration only for the use of Panamanian forces, mainly to fight drug trafficking.But John Lindsay-Poland, program director for the US-based pacifist group Fellowship of Reconciliation and most probably the top non-governmental expert on US military activity in Panama, has been digging into US government budget reports and the advertisements of US mercenary corporations to get closer to the truth of the matter. Part of the problem with mercenaries, however, is that by the terms of their contracts with the US government and the “private company” status that is used as a shield against the Freedom of Information Act and scrutiny by the US Congress, the things that mercenaries do are well hidden from the American people and the citizens of the countries in which US mercenary corporations operate. Moreover, in these days of globalization jobs that used to be performed by US soldiers, including combat, are now often outsourced to companies that are not even based in the United States. What Lindsay-Poland is doing, then, is piercing the corporate veil of privatized warfare, at least to the extent that he can.

Hugo Chávez has a reputation for making erratic and exaggerated statements, but so does Ricardo Martinelli, who boasted in the Italian press that he’s the “anti-Chávez” and has done much to distinguish himself as something of a right-wing mirror image of the impulsive Venezuelan leader. So who’s telling the truth about those bases in Panama, and are Venezuelan tales of drones over their territory necessarily a case of paranoiac ideation in high places?

And what about the suggestions, coming mainly out of Colombia and making their rounds in the Latin American left, that the string of setbacks suffered by the FARC guerrillas are not and could not have been as the government in Bogota describes them? Among the suggestions are that US surveillance or attack drones have played major unacknowledged roles in some of the high-profile assaults on FARC.

The drone question becomes relevant because among the many US Department of Defense contracts that were peformed, are underway or are to be carried out in Panama that are listed on the Excel spreadsheet obtained by Lindsay-Poland, highlighted in red on lines 359 and 585, are US Navy contracts with Stark Aerospace Inc., including for “mission support” and “persistent support.”

Who is Stark Aerospace? They are a US subsidiary of Israel Aerospace Industries, and the makers of UAVs — Unmanned Aerial Vehicles, or drones — including the Hunter, a short-range (about 144 nautical miles) surveillance and attack vehicle that the United States has used in Iraq, Afghanistan and Pakistan. Among the parent company’s other military drones is the Eitan, which has a range of more than 4,600 miles. Whether or not the reports or rumors are accurate, then, it does seem that the United States has drones based in Panama that are capable of hitting FARC camps in Colombia, and may well have UAVs capable of patrolling the skies over Venezuela from here. The drones that the US Navy and Stark Aerospace have deployed or will deploy to Panama — the contracts about which we know were only recently signed, in September of 2010 — might also be used to patrol Panamanian territorial waters for law enforcement purposes.

We can be reasonably sure, from US Southern Command practices over the years, from the probable technological limitations of Panama’s police forces, from traditional US reticence about sharing advanced military technologies and from the Obama administration’s known suspicions that the Martinelli inner circle is infiltrated by the drug cartels, that no Panamanian hands will be at the controls of any drones that the United States deploys in Panama. The question is whether the Panamanian government will have any say whatsoever about, or even any knowledge of, the purposes to which the drones are used.

The Tropical Test Center, again

If the United States military is going to play the role of imperial cop, it needs to know how its boots, rifles, boxes of ammunition, herbicides and other products will stand up to the jungle elements. For decades in the old Canal Zone the US Army ran the old Tropical Test Center for this purpose. Mostly it was non-controversial, but they probably did test Agent Orange here during the Vietnam era and later they tested depleted uranium shells and had to fire a few rounds, inevitably leaving behind a bit of toxic metal dust.

The Tropic Test Center was supposed to go along with the rest of the US military presence at the end of 1999, pursuant to the 1977 Panama Canal Treaties. But it seems that this never happened, that the facility moved from its previous locations in Panama to other places on the isthmus and was devolved from the US Army to mercenary contractors. Lindsay-Poland has traced the continued operation of the Tropic Test Center back to at least 2006, via the Houston-based Kvaerner Process Services back then and currently under the aegis of Las Vegas-based Trax International. Trax has historically done defense work at the Yuma Proving Grounds in Arizona.

Trax, whose CEO Craig Wilson is a major Republican contributor, describes its work and capabilities in Panama as follows:

Our experienced test personnel conduct tests in the humid tropic environment of Panama. Available test areas are within lush vegetation in the central portion of the Isthmus, and along the northern coast of Panama. All test sites are within close range of Panama City.

Existing capabilities include:

* A standard 700-m range

* A 3-km rugged jungle course

* Areas for prolonged tropic exposure tests in the open and under jungle canopy

* Engineering, information technology and logistics support services on site

* Coastal sites for various levels of salt spray exposure

Humanitarian missions, plus…

The US Armed Forces from time to time send medical and construction missions down to Panama and several of the other countries in the region. They rapidly set up temporary bases of operation with all of the facilities needed to support members of the work teams, then head out to provide medical, dental and veterinary services to people in remote areas who usually don’t get these, and to build or improve schools, health care facilities, bridges and other civilian infrastructures. It’s a good way to make friends for the United States.

On the construction end of it, it’s an opportunity for military engineering units to get some practice that, due to business and labor pressures, is not allowed in the United States. On the health care end, it’s an opportunity for guard and reserve doctors and nurses to see tropical diseases that they won’t encounter in the USA.

And what else does a US Army Corps of Engineers publication that Lindsay-Poland uncovered say to describe its humanitarian missions? Something bound to annoy nationalists in the countries where it goes:

Every Soldier a Sensor

- USACE DA Civilians/Soldiers can collect information and/or provide intelligence

- Provide entry point into country

A return to the firing ranges controversy?

One of the sore points about how the Panama Canal Treaty was implemented was about the several firing ranges that the United States had used over the years here. Some were outside of the old Canal Zone and thus not covered by the treaty, but some were not only in the old Canal Zone, but adjacent to communities whose residents sometimes came onto the ranges to hunt, gather jungle fruits or look for metal object to sell to recyclers. Unexploded ordnance on those ranges was and is dangerous, and over the years more than two dozen people have been killed by old munitions encountered on those places. Yes, there are signs warning people to keep out, but to a boy who has little concept of death, or to a man who lacks a job but has a family to feed, the temptations to ignore the signs and run the risks can be great. The treaty provided that the United States would remove all hazards insofar as practicable, and Washington took the position that because it did not want to spend the money to clean the firing ranges it was not practicable to do so.

Panama ignored the issue the last few years before the final US military withdrawal, but then the Pérez Balladares and Moscoso administrations, which had no real interest in cleaning the ranges, attempted without success to shake down the US government for cash payments in lieu of range cleanings. Panama has cleaned part of the Empire and Balboa ranges as part of the Centennial Bridge construction and Panama Canal expansion projects, but for the most part the old ranges remain uncleaned.

Now it turns out that among the more than 700 US Department of Defense contracts carried out in Panama since the bases closed at the end of 1999, we find a September 29, 2010 contract with Austin, Texas-based J&J Maintenance, to “upgrade ranges.” Which ranges? We only have the spread sheet that refers to the contract, rather than the contract itself, so we really don’t know. Lindsay-Poland points out that “this could be linked to the bases and collaboration with SENAN [Panama’s National Aeronaval Service], or to the Tropical Test Center, or both. It’s a concern.”

Those aeronaval bases

Certainly the assurances that the Martinelli administration gave with respect to a foreign military presence in Panama were false. But are these bases strictly for interdicting drug traffic, or for something else as well? On the contracting spreadsheet that Lindsay-Poland obtained, the base projects bore the code “CNT,” for “Counter-Narco-Terrorism.” In standard US military usage, that means the fight against FARC but not against garden variety criminal gangs or Colombia’s drug-funded right-wing paramilitary groups. Sociologist and political analyst Marco Gandásegui pointed out that:

Late last year the Defense Department signed a contract for a total of $4 million to build military barracks and a dock with military capabilities in “Puerto” Piña [on Piñas Bay in the Darien]. The place where the investment in the military barracks will be made (or is already being made) coincides with the area in which the Panamanian government denounced the existence of a FARC camp.

The spread sheet on the contract also provides a few more details on a situation that contributes to the Martinelli administration’s poor standing with the country’s indigenous communities, as it refers to bases in El Porvenir and Puerto Obaldia, which are in Kuna Yala. Puerto Obaldia is a predominantly Afro-Panamanian (and Afro-Colombian) enclave in the quasi autonomous Kuna commonwealth, but El Porvenir is in the heart of Kuna country, where the local authorities have made it abundantly clear that police or military bases are not welcome.

For his part, Lindsay-Poland has found some interesting things, but wants to learn more:

CNT refers to Counter-NarcoTerrorism. There are other projects that are funded by CNTPO, which is the Counter Narcotics Technology Program Office of the Pentagon.

These could imply either US or Panamanian use. That’s why I think pushing for disclosure of access agreements with the United States is key, as these would shape the terms of US use.