With a ruling due on time limits for investigating those with legislative immunity expected on August 13, even if the limit is upheld the prosecution has received an extra 42 days of information on Martinelli’s spy schemes

Hardball over time limits

by Eric Jackson

It would be interesting to know what top police commanders and US diplomats told Ricardo Martinelli in the final weeks before the May 2014 elections. The former president had stolen hundreds of millions of dollars from the public treasury — some directly, some by overpriced contracts with kickbacks to the Cambio Democratico campaign — to shower gifts on voters. The police had stockpiled huge arsenals of anti-riot munitions. Virtually all online media that Martinelli did not control had been hacked. Every appearance was that whatever the voters said, the former president intended to hold onto power through his proxy slate. It would seem that somebody with superior power to bring to bear warned him to desist.

But maybe not. There was also a Plan B in motion. The Martinelli administration and the legislature it controlled had passed laws to make it difficult to prosecute themselves for crimes that they had committed. One of these was the addition to the Code of Criminal Procedure that limits the time for prosecutors to carry out an investigation against someone with legislative immunity to two months from the time the investigation starts. If formal charges are not brought within that brief window of time, then the case must be closed and the matters it addresses may not be brought up by the criminal justice system again. As a former president, Martinelli became a member of the Central American Parliament and would be covered by this privilege.

However, Panama’s often ignored constitution says a few high-minded things about equality before the law. Article 19, for example, prohibits privileges, immunities or discrimination on the basis of social class. So is Ricardo Martinelli’s self-protection amendment to the rules of criminal procedure the creation of a social class with special privileges and immunities?

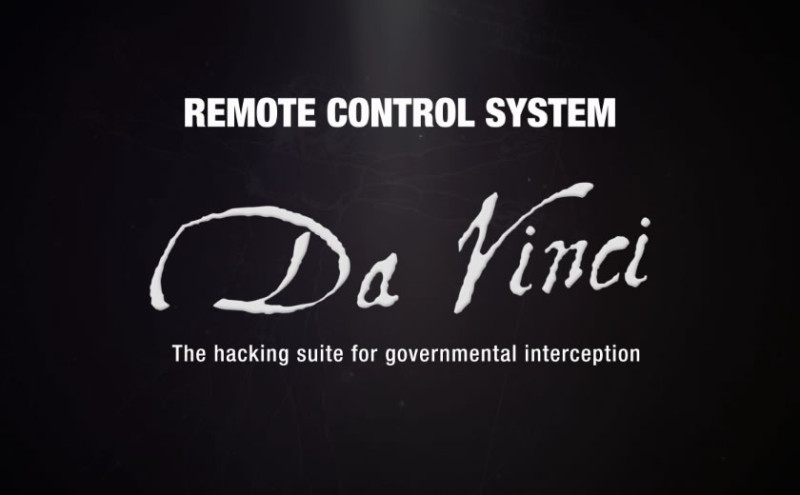

The second of several criminal cases against Martinelli to get to the Supreme Court is about illegal electronic eavesdropping. It’s a difficult case because key figures have gone into hiding, the equipment used has gone missing, foreign contractors have clammed up and the basic facts of what happened were hidden under veils of “national security” at the time. But two former national security directors are under arrest and talking, charges have been requested against a third, audits have uncovered money trails and international hackers have hacked into the data of one the key foreign contractors, Italy’s private company Hacking Team, and published those data. The Public Ministry has been investigating people without legislative immunity all along, and much of what they find either implicates Martinelli or gives leads to other sources that are likely to do so.

So on July 2 there was a hearing in Martinelli’s eavesdropping case, with defense counsel seeking to prolong matters so as to run out the time for an investigation. But the high court’s prosecutor in the matter, magistrate Oydén Ortega, filed a constitutional motion challenging the special time limit. That stopped the countdown and most of the proceedings against Martinelli, save the previous motion in the Electoral Tribunal to lift the former president’s immunity.

While that freeze was in place, more facts about the surveillance program became known. It turns out that there were at least four major contracts involved, three for electronic equipment and one for software. It turns out that some of the hardware was bought through a company owned by the ex-president’s brother-in-law, Aaron Mizrachi. When that connection became public knowledge through reports in La Prensa, Mizrachi went to Albrook airport and took off in Martinelli’s private jet for Miami, where like the ex-president he is now in self-imposed and us-tolerated exile.

On August 10 the Electoral Tribnal rejected a motion for reconsideration of its order lifting Martinelli’s immunity. So when the full Supreme Court rules on the challenge to the shorter time for investigations legislators — in another case, not on Ortega’s motion — will Ortega have just 60 days to investigate if the rule is upheld? In effect, he’s already had a month and a half more than that.