Scalia’s replacement and the 2016 elections

American history — including the English and European history as understood by the founders of the American republic — was a subject that Antonin Scalia routinely and pointedly disregarded. With his demise begins a constitutional crisis of sorts, or more properly, an episode that will illustrate and aggravate divisions that have already rent US society. Because the Common Law legal system is mostly based on history as recorded in the precedents of case law, and because the US Senate that must confirm any presidential nomination is bound by its own arcane historical traditions, the demise of a justice who infamously rejected all inquiry into legislative history and intent has already touched off ferocious arguments about history.

Think of what Scalia’s rejection of history meant. The 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments were products of a terrible Civil War fought over the future of the institution of slavery into which most African-Americans had until that time been born — but since these parts of the Constitution did not mention race, Scalia denied that race had anything to do with them or was an issue cognizable by American law. Because he refused to look at the historical abuses of the Plantagenet kings and their henchmen that gave rise to the Magna Carta, which in turn informed the expectations of the American colonists, Scalia essentially held the terms “privileges and immunities” and “due process of law” to be meaningless and went on to opine that torture and the executions of innocent persons are perfectly legal. This stuff about Scalia being a “strict constructionist” is a partisan myth — he had a right-wing agenda and he wasn’t averse to erasing parts of the Constitution to get results in line with that program.

So what does the Constitution say about how people become members of the US Supreme Court? It gives the President the power to appoint, but the Senate the power to approve or reject such appointments. With the present political gridlock, there is a good chance that any Obama nominee would be rejected out of hand. It would not be the first time that a nomination fell victim to a power struggle between the executive and legislative branches, nor would a short-handed high court be unprecedented.

As constitutional crises go, this one is a potential yawner. But maybe it won’t be, as there are other troubling things going on in the USA and among Americans everywhere. Consider the lunacy of the “constitutionalist” occupation of a bird sanctuary in Oregon — a criminal act by those whose external spokeswoman is a Republican member of the Nevada legislature. Consider Donald Trump’s vow to cancel the part of the 14th Amendment that reads “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the state wherein they reside.” If the voters put Trump in a position to do it, he would deport the US-born children of Latin American immigrants whose papers were absent or deemed insufficient and roll back the statutory citizenship rights of those born abroad to American parents.

The next court may have to deal with attempts at radical surgery on the Constitution, but were that the only issue Obama would not have much trouble getting his nominee approved. Litmus tests are in play, but not particularly Donald Trump’s. Nor, we should expect, would be the political hot button issues of guns, gay rights or abortion. The two irreconcilable issues are likely to be institutionalized bribery — the principle of the Citizens United decision — and vote suppression, now on the rise since the Shelby County decision gutted key provisions of the 1965 Voting Rights Act. Given the demographic and political shifts shown by Barack Obama’s election and re-election and by the strength among young voters shown by Bernie Sanders early in the primary season, vote suppression is an existential need for Republicans. The institutionalized bribery of unlimited campaign spending is an existential need of many members of the political caste in both major parties, but above all of the Republicans. It is also critical to the profit margins of the television networks and to the continued political protection of many a wealthy and now powerful business interest. Obama is unlikely to nominate somebody who can be trusted to keep vote suppression and institutionalized bribery in place, and the Republicans who control the Senate are unlikely to confirm a nominee who would overturn these principles, which would have never become law without the fifth vote of Antonin Scalia on the high court.

Now we are left with a short-handed Supreme Court, which by 4-4 ties would uphold the lower court decisions without setting binding precedents. One heartbeat gone silent has stalled the rightward march of American jurisprudence. The stakes of a 2016 election that had already promised to be a big showdown have suddenly grown. The maneuvering and posturing over Scalia’s replacement is likely to become a central part of the election debate, one that may just by itself put control of Congress in play.

So now we get back to history, with various twists proffered. Is it illegal or improper for a president in the last year of his term to nominate someone to fill a Supreme Court vacancy? No. It has happened several times. Is it illegal or improper for the Senate to block a president’s late term appointment, leaving that spot to be filled by the next president? It’s certainly not illegal and has been done before, but propriety gets into a philosophical discussion about the motives.

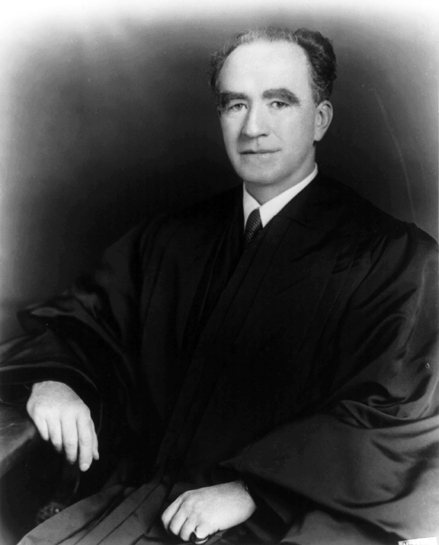

The precedent that will be dissected and cast in different lights is Lyndon Johnson’s nomination of Abe Fortas to be chief justice back in 1968. An alliance of Republicans and segregationist Southern Democrats killed that nomination in a Senate filibuster and the vacancy was left for Richard Nixon to fill. Nixon was elected president about a month after Fortas’s rejection, in an election that shifted US politics sharply to the right for more than a generation. Add to Nixon’s GOP vote total the votes that segregationist George Wallace got as an independent and that’s nearly 57 percent of the vote. Four years later with the power of incumbency behind him Nixon upped the then united right-wing share of the vote to nearly 61 percent, winning in an historic landslide.

The issues and balances in Congress have changed since the 1968 fight over Fortas, but far more strikingly the country and the natures of its main parties have changed. It’s not wartime prosperity for a growing middle class, but endless wartime despair for a shrinking middle class and especially those below. Democrats are split not between civil rights and segregationist wings, but between those who are obedient to corporate orders and those who aren’t. Republicans have an old guard establishment that’s widely repudiated by the party membership and a rumble among hustlers and weird cults to pick up the pieces.

Will a party boss rigging the nominating process to give the Democrats Hillary as a standard bearer be a repeat of the 1968 Hubert Humphrey debacle? Will an insurgent campaign that makes Bernie the nominee be the formula for a Democratic defeat on the order of the one suffered by George McGovern in 1972? Those are things to bear in mind, but the 2016 electorate, the national mood and the American economy are all very different from back then.

The Latin phrase about legal history that we are likely to hear bandied about in coming months is stare decisis — the Common Law predisposition to follow history and leave settled legal precedents alone. When Teddy Roosevelt curbed the abuses of the Gilded Age and broke up the Robber Barons’ trusts, Americans heard protests about the damage that did to the policy of stare decisis. When Franklin D. Roosevelt moved to end a Great Depression that resurgent corporate power had visited upon the land, he had to do battle with a Supreme Court that time and again cited stare decisis in favor of corporate privileges. When the Supreme Court under Earl Warren’s leadership moved to end Jim Crow segregation, the Koch brothers’ dad was one of the far right activists crying stare decisis and advocating Warren’s impeachment for a series of civil rights decisions that overturned previous case law. Of course it becomes rather difficult to do business if the law becomes arbitrary and uncertain, but in US law the power of precedent has been overcome time and again to meet basic national needs or to correct glaring injustices.

Let the games begin, let the litmus tests be applied, but do your own history homework.

Bear in mind…

~ ~ ~

The announcements below are interactive. Click on them for more information