A truth about ‘post-truth’

by David D. Judson — Stratfor

Nearly a month has passed since American voters gave the presidency, seemingly against all odds, to Donald Trump. And for nearly a month a global chorus of pundits, pollsters and media prophets have asked: How did just about everyone get it wrong? Amid the hand-wringing, the list of culprits is long: Skewed models of voter bases. The demise of landline telephones. Underestimates of “lapsed voters.” The evolution of game-changing social media. Wishful thinking.

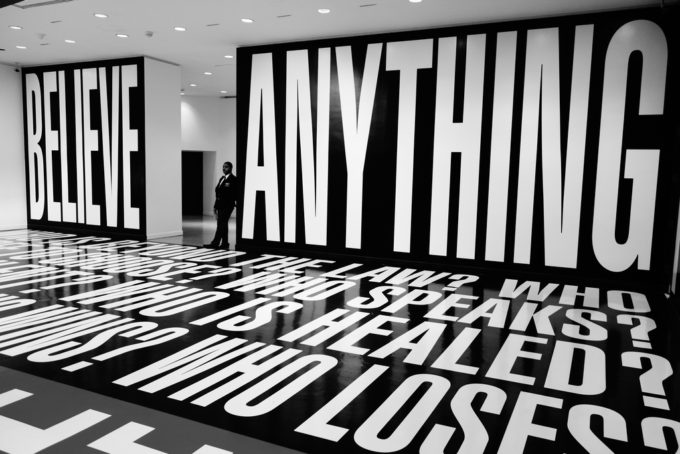

In the stream of post-election postmortems on journalism’s performance, “post-truth” is the handiest of explanations in a campaign season that took fibs and fabrication to a new level. The Oxford English Dictionary has declared “post-truth” its International Word of the Year. A Google search on the term yields some 240 million results. Layer what the candidates said against the “fake news” manufactured on Facebook and elsewhere and, for some, this is all but a civilizational threat.

But the term is actually older than we think. It was coined back in 2004 by the author Ralph Keyes. It took a while, but now it has transformed into a new meme alive in the media ecosystem. It is an illustrative case study of how memes emerge and dominate discourse, refracting perceptions of political reality.

But first, a bit of background. The term “meme,” devised in 1976 by sociologist Richard Dawkins from the Greek “mimema,” or “something imitated,” was originally used to describe patterns of belief that spread vertically through cultural inheritance (from parents, for example) or horizontally through cultural acquisition (as in film or media). Dawkins’ point was that memes act much like genes, carrying attributes of beliefs and values between individuals and across generations. It is even a field of academic study known as “memetics.”

The best of intentions

Today the term meme is more popularly applied to videos, a bit of text, a viral tweet, becoming a fixture, a short-lived canon if you will, in social media-driven consciousness. “Post truth” is just one in a long line of them.

Which is not to be dismissive of the underlying issue of partisans planting fabrications into the echo chamber of partisan news media. I share the alarm at the speed with which misleading charges or downright falsehoods can spread through the Twittersphere. And it’s not just an evil embedded in presidential campaigns. The new media age has many dark sides. I worry about “covert influence” that state intelligence agencies — and not just Russia’s — can and do spread. Social media as a tool of terrorist recruitment is a real threat. While writing this column, I chanced across the news that Facebook (inadvertently I’m sure) enabled a far-right group in Germany to publish the names and addresses of prominent Jews, Jewish-owned businesses and Jewish institutions on a map of Berlin to mark the 78th anniversary of Kristallnacht.

Still, you’d think from the post-truth discussion that darkness was descending to devour an age of veracity, candor and honesty in our public discourse. The assault on authenticity, however, isn’t anything new. The cry “Remember the Maine” animated the Spanish-American War of 1898 with false claims. The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, a complete sham, was first published in Moscow in 1903 and its lies are still disseminated, and believed, throughout the world. The “missile gap” of the 1950s is closer in history but no less untrue. Many readers are old enough to remember the misleading Vietnam body counts of the 1960s. Or think of Saddam Hussein’s purported weapons of mass destruction and a war that rages on some 13 years later.

Malicious intent, of course, is at work in the willful propagation of falsehood. But the narrative rivers of the media world all too often ignore the good or evil of their tributaries. Said differently, forest fires spread faster by creating their own wind; more often than not, the oxygen of the mainstream media is a meme or something like it. And it is often carried forward by journalists with the best of intentions.

Tying reality to the soil

I’ve written before that this propagation lies at the heart of the difference between journalism and intelligence, so I won’t belabor the point again. But a few examples are worth examining. The Arab Spring: It never really existed, and we said as much. The intractable clash between the United States and Iran: Our forecast of rapprochement was widely met with skepticism, but then it came true. The inexorable rise of China: It’s not inexorable, and we write about this frequently. The new Cold War: It’s not a good analogy to the current standoff between Russia and the West. The “ever-closer” European Union? Well, no one’s making that argument now. But when we first challenged it years ago, we were considered heathens.

And we’re still heathens. As to the specifics of this election cycle, we’re not going to run a victory lap; we didn’t forecast the outcome because we don’t forecast elections. But we do analyze the global dynamics at play in elections, including rising nationalism, nativism and trade protectionism in the West — themes that echoed throughout the presidential campaign. For us, the overarching issue is not how Trump vanquished Hillary Clinton. It’s how the United States will behave under these new circumstances, which are unreadable to international leaders, elites and publics — but not to us.

Can we expand our methodology to North America? Yes, we can and we will. But we won’t start doing it with existing narrative or memes. The work of geopolitics, one sage of the craft has said, “rids politics of arid theory and senseless phrases” by tying “permanent reality to the soil.” So we will start by looking at the map.

We are not in an era of post-truth. We are in an era of post-meme, at least at Stratfor. And challenging memes, I’ve come to be believe, is at the heart of what Stratfor does.

Questions? Concerns? Drop me a line.

David Judson

Editor-in-Chief

djudson@stratfor.com

A truth about ‘post-truth’ is republished with permission of Stratfor.

~ ~ ~

These announcements are interactive. Click on them for more information.