Showdown in the National Assembly

by Eric Jackson

The sun comes up on Monday, March 12 with confrontation in the air. The day before, protesters from the Limpiemos Panama movement started by television comedy and satire producer Ubaldo Davis Sr. were out in front of the legislature. The body’s president, Cambio Democrático legislator Yanibel Ábrego, has attempted to obstruct visibility of the protest by posting Panamanan flags along the fence facing the legislative park, but as the protest continued that just served to concentrate the crowd on the side street, compacting it so as through cameras it appeared to be all the larger.

Ábrego is one of a majority of deputies named in a request for a criminal investigation by Comptroller General Federico Humbert, for abuses of circuit funds during the Martinelli years. The general scheme was to funnel these funds, which ordinarily are subject to audits, through the neighborhood governments — juntas comunales — of compliant representantes. The financial transactions of a junta comunal are not subject to audits, this being one of the central quirks of its time in the 1972 political patronage deal between representantes and the military dictatorship that is the constitution that still rules the way that Panama governs itself. There is a public demand to prosecute all of the legislators who so routed their circuit funds for money laundering, and some of them whose expenditures did become known by other means for embezzlement. But the prosecutors of the Public Ministry do not have nearly enough forensic accountants to handle such a volume of cases and it’s doubtful that the legislature would give them the funds to close that gap. Given that President Varela’s brother is one of the deputies named in connection with the abuse, it’s doubtfult that the president would ask for such funding.

Instead, the National Assembly has on its morning agenda the selection of a new Credentials Commmittee whose membership reflects the constitutional mandate that its partisan composition roughly reflects that of the legislature as a whole. Talks toward that end broke down and the president’s 16-member Panameñista caucus (of 72 legislators in all) asy that it will not participate in the voting or take any positions on a reconstituted Credentials Committee.

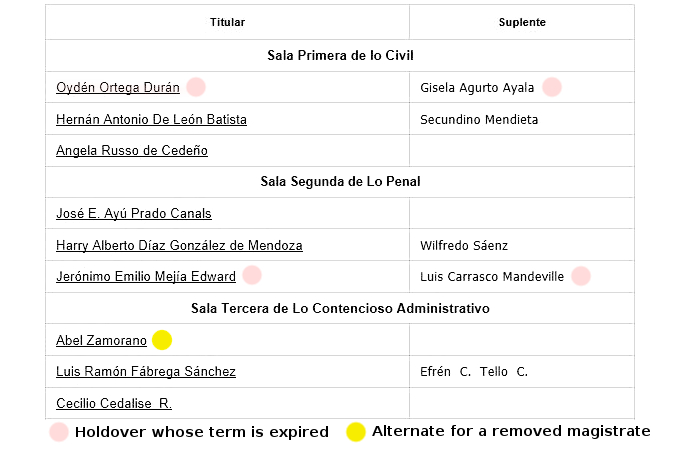

The Panameñistas are counting on a Supreme Court stay. At the end of February they had filed an “amparo de garantias” — a constitutional challenge — to a resolution to dissolve the old Credentials Committee, in which the Panameñistas had four of nine votes, and acting magistrate Abel Zamorano accepted the case. Under ordinary procedure, that means that there can be no more action on the challenged procedure and the high court as a nine-member body sets aside all other business for the moment to decide if the case shall proceed. But that has not happened and there appears to be no schedule for it to happen. The plan, so it seems, is to suspend the legislature’s action and let any judicial consideration of the matter slide until it becomes moot.

Whatever happens, President Varela’s last two nominees for the high court were rejected and he doesn’t have the votes for new ones unless some compromise is reached. If the Zamorano stall works, then on July 1 the legislature has its organizational meeting for its last year in office, part of which is the new committee assignments. The Panameñistas don’t have the votes to get more than their share on the Credentials Committee at that point.

So what’s the big deal about this committee? It’s the body that would handle the impeachment of any president, cabinet member or high court magistrate. In the end the plenum of the legislature would have to accept anything that the Credentials Committee approves, but if the PRD and Cambio Democratico caucuses unanimously agree, between the two of them they have more than the 48-vote super-majority for a conviction.

President Varela bellows that he will assert his authority. PRD leader Pedro Miguel González bellows that the legislature will not be blackmailed. Acting magistrate Zamorano may have issued his preliminary ruling, but he and his colleagues are holding their tongues since then — for one thing, their own credibility is down in the pits with the legislature’s, and for another they are very short-handed even if business continues more or less as usual. The usual arguments about separation of powers have been by legislators annoyed by a strong presidency increasing its powers, but he judicial branch is also supposed to be separate and autonomous and its authority to decide legislative committees is being challenged as an intrusion into the affairs of another branch of government.

Looming over all of this is the fact that three witnesses and a paper trail say that President Varela took millions from the Brazil-based criminal corporation Odebrecht, and that after initial flat denials Varela changed his story to say that it was a campaign contribution. It’s the making of an impeachment case if the votes are there. But where are the votes in the legislature? Where are the votes on the high court? If push comes to shove, whose orders will the police follow?

We are about to witness another showdown in a battle among three much-weakened branches of the Panamanian government.

The current composition of the Supreme Court