This American Revolution of ours…

by Eric Jackson

On the Fourth of July, 2018, especially but not only for my English-reading friends who are not citizens of the United States and may not know. But then, with the decline of US education a lot of Americans also do not know.

To understand the American Revolution you have to know something of what went before. See, these were mainly British colonists, who were used to the English Common Law that’s largely based on historical precedent, as received by people of their time, which was after the Magna Carta and the Long Parliament limited the king’s powers and established that people have rights, and after the wars and persecutions of the Reformation had largely come and gone.

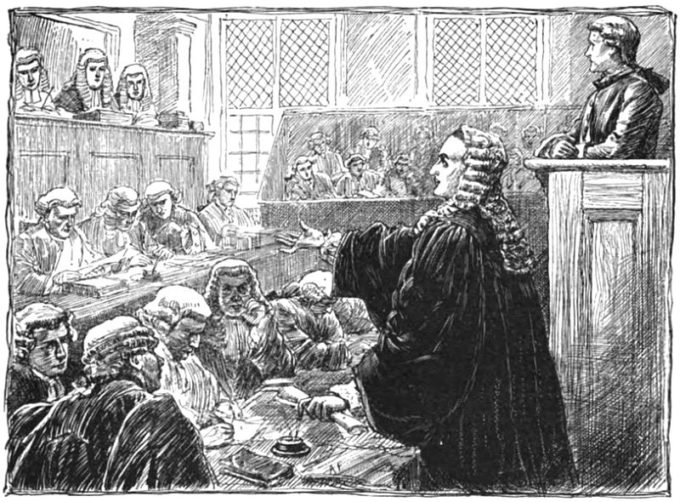

One precursor of the American Revolution was the case of John Peter Zenger, in which that publisher of the New York Weekly Journal was in 1734 charged with libel for an admittedly true story he published, but it was argued that as in England, truth is not a defense to a story that injures a prominent person’s reputation and might disrupt the established order. But in that case the jury decided that in the New World it would be different, that truth is a defense to libel. That rule stuck in America.

It came down very largely to economics. Britain wanted colonies that served its interests according to its directions, while the Americans took on a national life and economic aspirations of their own.

The Yankee traders want to do direct business with the Spanish and French and Dutch and Portuguese colonies? No way, said the Navigation Acts. Those empires trade with the British to the extent allowed at the time, and the colonies import their products from Great Britain with all the markups that entails, and too bad if things go stale in transit. No way, said the Yankee traders, who became in short order smugglers, enemies of the British Crown.

The people who were sent over from the British Isles as indentured servants finish their time of servitude and want to go west to carve out farms of their own? You expect us to send in soldiers for the wars with the native nations that were there first that will come of that? No way, said the Parliament in London. Or at least, if you want to do that you have to feed and house the soldier we send in your individual homes.

Americans wanted to establish industries with the abundant resources that the British Isles mostly didn’t have. The British wanted extractive and plantation economies in America, to feed manufacturing that would be reserved for Britain. Especially for shipping, the colonies were required to produce wood, rope and sails for British shipping. Britannia was supposed to rule the waves, not America.

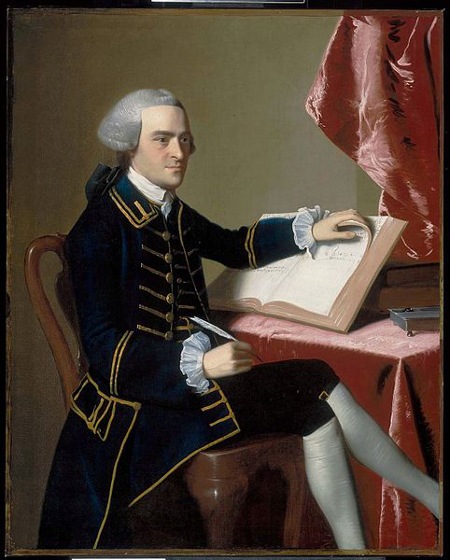

It got to imposed monopolies, unwarranted smuggling searches and seizures, taxes imposed from abroad from abroad with no consultation (let alone representation) and back-and-forth political battles over a period of decades. Push came to shove, and eventually people got killed. The first American to die was a black man, a former slave named Crispus Attucks.

A Continental Congress arose as the colonies’ unified political leadership and the situation degenerated into war. With war already underway, Congress declared independence on July 4, 1776.

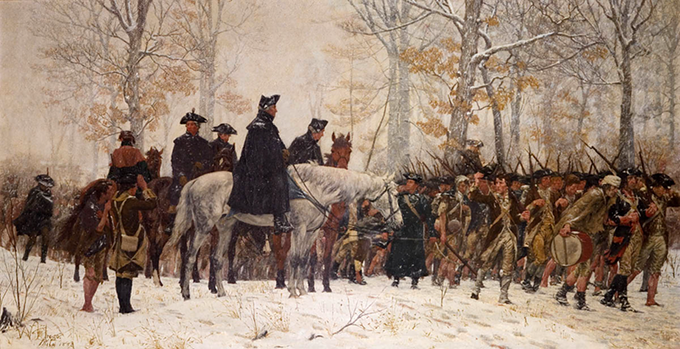

The war dragged on, with George Washington leading a guerrilla effort to keep up the fight but avoid a definitive defeat. Until nearly the end, there were a few battles won but mostly a long series of retreats. An Irishman later noted the nature of such things, that in the end victory goes not to those who can inflict the most suffering, but to those who can endure the most. And the Americans endured.

This war was not in isolation. The Brits were at war with many of their Continental European neighbors, in theaters spanning the globe. The French in particular thought that the Americans would be a good investment in their struggles with the British, and two polymath geniuses turned diplomats, Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson, did much to encourage such thinking in Paris.

The British were worn down, their generals made a mistake by moving their armies onto a peninsula, and between George Washington’s Continental Army and a French fleet, the British were forced to surrender at Yorktown.

After that Americans by and large didn’t know what to do. It was a small, poor country that had been bled and exhausted by a long war, and whose future existence was far from assured. Some of the demobilized troops got disorderly in the face of broken promises. The ruled of economic relations across state lines were uneven and often arbitrary. States were claiming overlapping dibs to lands to the west. So there was a Constitutional Convention that came up with a compromise between the two major power blocs, the Northern merchant and industrialist castes and the Southern slave-owing plantation masters.

The rest were left out, sort of. But to get the new governmental framework ratified, a Bill of Rights had to be passed. People could believe what they want and speak and publish these things. The new federal government would have to respect due process of law and restrict its intrusions into private lives. The authoritarian norms of governments on the other side of the Atlantic were more or less officially discarded, although within states, and especially with respect to black slaves and the original nations, the federal guarantees mostly did not apply.

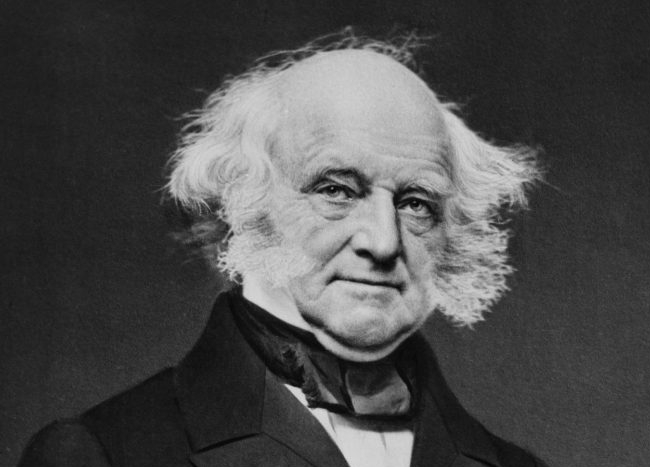

Quickly under the new constitution the ability to vote with feet and go west sapped the political power of landowners. Property restrictions on voting fell by the wayside. Northern states abolished slavery. The pretensions of established elites were disrespected. America even elected a president whose native tongue was not English.

By purchases, annexations and wars, the United States became a continental empire, embracing nations that had been there before any English-speakers ever arrived and which had little say in whether or not they wanted to be Americans. So how would this empire be arranged? According to the vision of the mostly northern industrialists, or according to the vision of southern slave owners?

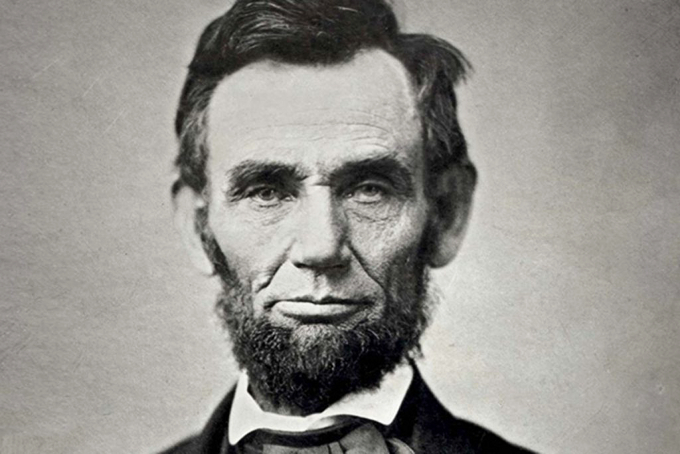

Political warfare, then guerrilla warfare, then a great Civil War ensued. It came to head with the election of a corporate lawyer for railroad interests, Abraham Lincoln, who did not initially aim to change slavery in the South but who represented a business model that could not thrive if slavery was extended into the West. More than 600,000 people lost their lives, a series of amendments legalized the end of the slave economy and federal power became ascendant over the power of the states.

The victorious railroads and industrial combines got increasingly abusive, to the point that their leading lights became known as the Robber Barons. Jim Crow laws snatched back a lot of the freedom that the former slaves had been granted. The original nations of the West were shot down and starved into submission. Massive immigration brought in people fleeing from Old World aristocracies and not so eager to subject themselves to American ones. Farmer and labor movements arose.

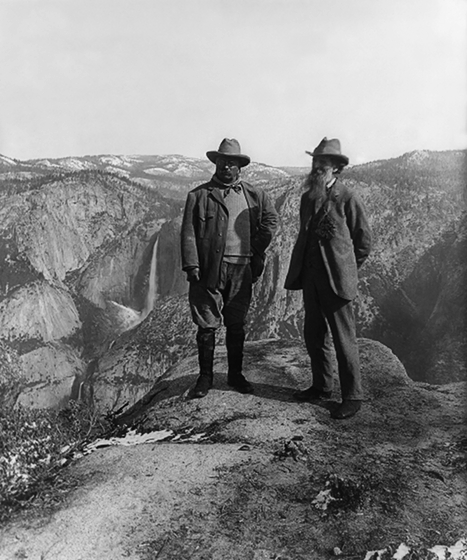

After decades of the Robber Barons’ unstoppable power, there came the Progressive Era, whose most outstanding characters were Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson. There were racism and imperial hubris – things not seen as at all “progressive” today – in that mix. However, direct election of senators, the graduated income tax, federal regulation of food and drug purity, national parks and protected natural areas, civil service systems, the decline of most of the urban political patronage machines and women’s suffrage also came in that mix.

World War I, political repression against leftists, a second rise of the Ku Klux Klan, xenophobia and the Roaring 20s when Wall Street speculators and their faction of the Republican Party reasserted control brought an end to the Progressive Era. The bubble burst late in 1929, but it wasn’t until after the 1932 election that the politics of the post-Progressive Republicans, or as Franklin D. Roosevelt came to call them, the “Economic Royalists,” came tumbling down.

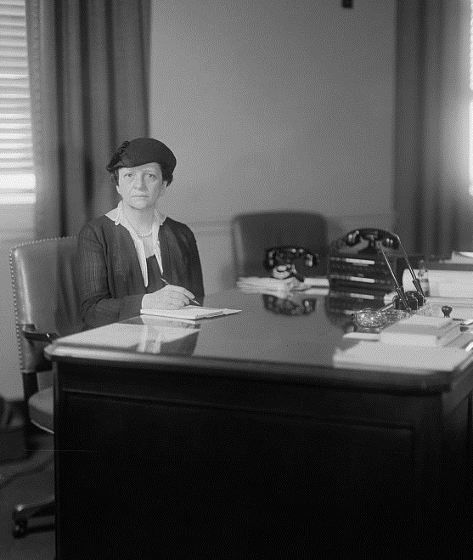

FDR was from an aristocratic clan and not particularly a radical. But the country was deep in hole and his New Deal tried many things to get it out, often under pressure from a resurgent labor movement. Two women in particular, the first lady Eleanor Roosevelt and the first woman to serve in a cabinet post, Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins, pushed the country in directions of economic democracy and respect for human rights. But it took wartime production to get the economy going full blast again.

In the war the epitome of racism, Nazi Germany, was utterly defeated and in its wake a great drive for civil rights for African-Americans gained strength. Throughout the 50s and 60s the pressure built and in response there arose the third iteration of the Ku Klux Klan.

The postwar rivalry with the Soviet Union and the domestic red scare that accompanied it had dumbed down permissible discourse in the USA, but the civil rights movement and opposition to a long and losing series of wars in Southeast Asia broke the imposed silence. Richard Nixon and Spiro Agnew, the principal voices of “The Silent Majority,” turned out to be tawdry crooks. That revelation provided a brief respite for the progressive forces.

But under Nixon the postwar Bretton Woods set of international economic arrangements began to break down, and replacing it was the rise over several decades of “globalization” on corporate terms. The USA became a meaner, less equal place despite many efforts to halt or reverse that process.

America finds itself in a terribly reactionary period, but the revolution’s spark has never gone out. We can trust that younger generation will keep this long running project, this centuries-long dream, on course for another national renovation.