A Peace Corps learning session at the Lazy Man’s Farm

story and photos by Eric Jackson

So, on an isthmus with an agricultural history of more than 10,000 years, what farming and land use practices can be sustained against changing climatic conditions? Archaeologists, paleobotanists, climatologists, ecologists and other specialists still have a lot of work to do but what the known record suggests to this writer is that many things do not get sustained, that communities and cultures have come crashing down for various reasons and have had to start again almost from scratch.

(Do we want to sound modern and unprecedented and alarmist about human causes? Animals were hunted to extinction in prehistoric times, and then in the historically known European Conquest the ravages of war but to a far greater extent the plagues uwittingly brought by the Conquistadores also left their marks on the land. Jungles grew back in areas that had long been cleared and farmed in Panama’s great human die-off starting in the 16th century.)

But for sustainability in the face of climatic changes we can look, if not so much here, to terraced hillside farms in Asia and South America. These look like they were a terrible amount of work to create, which sells books and movies for hustlers speculating about visitors from outer space. There WAS quite a bit of labor involved, but mostly by plants and elemental forces. How a lazy man can harness such forces and make the land produce and thrive was the gist of farmer John Douglas’s presentation to Peace Corps volunteers, members of an organization of which he was once a part.

La Finca Perezosa, a hillside along a half-mile stretch of the Zarati River, was fairly barren when Douglas took his retirement from the Peace Corps without ever giving up his vocation as a teacher and promoter of organic permaculture. That is, farming in which the things that are cut down are not burned but allowed to decompose more or less in place, ploughs never break the soil, chemicals ae not dispersed and this weird Panamanian sense of the word “limpiar” — to “clean” the land by killing every living thing on it and leaving only bare soil — is quite the dirty word. Douglas tries to balance and direct nature, letting elemental forces do most of the heavy lifting and keeping a diverse and mostly edible jungle growing throughout the seasons.

For example, by the use of swales, to which he attributes the famous terraces of the Andes and parts of China. Backbreaking labor? Well, maybe just a little. Mostly, stones laid athwart where the water washes down the hillside in heavy rains to slow and spread the flow, followed by a swale — a trench perpendicular to the slope — to make the water slow and spread some more, and then on the down side of the swale the planting of things that hold the soil, absorb the water and direct leaves and other solid stuff washed by rain or blown by wind into the trench. The muck that builds up in the swale is both the good black dirt in which to plant things but eventually this raised earthen terrace held in by the balo trees (the main plant used in Panama’s living fences), sunflowers or other apt plants. Those thousands of years old trenches here and there around the world? Neither armies of slaves nor sophisticated spacefarers with amazing machines are to be blamed, albeit there was a bit of human labor involved. Once the swales were dug and their edges planted, elemental forces did the rest of the work.

So, what to grow? Douglas has about 350 fruit trees on the property, some wood trees, plenty of vegetables and tubers — but more than anything he is growing SOIL. In some spots, particularly were water runs off of his house, Hugleculture. With swales you dig a trench but with this method you may or may not do any digging. The idea is that, with rotting wood — chips or otherwise — at the bottom you add more layers of organic compost until there is a raised planting bed. Soil fertility and water retention are enhanced, and a household can feed itself in a small space by planting the right things on or around such biomass mounds. A number of the volunteers took Douglas up on his offer that they could take cuttings from the mound just downhill from where we had breakfast a few hours earlier.

This, of course, is Panama. Reports of headhunter tribes are greatly exaggerated, although there have been human resources people spotted in places like Coronado and Panama City. But a densely planted permaculture farm of which you can’t see every corner from your balcony poses certain pilferage risks. These can be more or less intelligently managed.

Do you want to be a gringo gunslinger ready to pull the trigger on all predators? You may say that Indiana wants you, but if you are one of those actually Indiana thinks that you’re a jerk. And so will Panama. Guns are restricted here, as is hunting. You are not welcome to shoot predators, human or animal, in this country.

At the Lazy Man’s Farm there are wild animals — mostly arboreal things like sloths, monkeys and at least 72 species of birds. A bit of animal predation, and the occasional kid sneaking onto the property with a slingshot to get an iguana to put in the pot, is part of nature’s balance. So is the appropriate planting of a few fruit trees where animals or people may be expected to glean or graze. On the far edges are the spots where you also want to plant wood trees.

But the food crops on which your lifestyle depends? Keep THOSE gardens close to the house, where you can see them and where the usual fruit poacher will be afraid or embarrassed to be discovered stripping the farm. Yes, it’s organic permaculture and it looks pretty wild, but actually John Douglas’s farm is not a random scattering of plants.

Then there is one of Douglas’s favorite tricks, especially with the gray water from his house, but amenable to many situations: the magic circle.

Holes collect water and organic debris. Back in New Deal WPA time, when the Dust Bowl had added to burst stock speculation bubbles to make the United States miserable and Franklin D. Roosevelt assembled a brain trust trying to figure out what to do, one of the ideas was to make the western deserts bloom. As in, to roll over them with something that looked like a steamroller with spikes coming out of the cylinder, to punch all of these holes in the arid dire. Dust and spores and seeds collected when the wind blew over the holes, and come the infrequent rains, stuff sprouted out of the holes and bloomed. It looked pretty enough, it marginally reduced the dust storms, but all the people who decided that they wanted to live near the desert flowers and the Roosevelt era reservoir projects skewed the calculations of environmental benefits and damages. Did the folks who made lines in the Atacama Desert have a similar idea way back when? Holes collect water, promote growth and add structures to the land.

The seminar ended with the creation of a magic circle. A shallow hole was dug, the excavated dirt around the edges in a doughnut shape. A plantain went in the middle, various greens and tubers around the edges. As the plants are things and there are clippings of this or that, or plant waste from the kitchen is generated, that stuff goes down into the hole. You get this little ring of organic biomass that the plants love, especially if the kitchen sink drains out into it. And so it was done, and Douglas explained why.

~ ~ ~

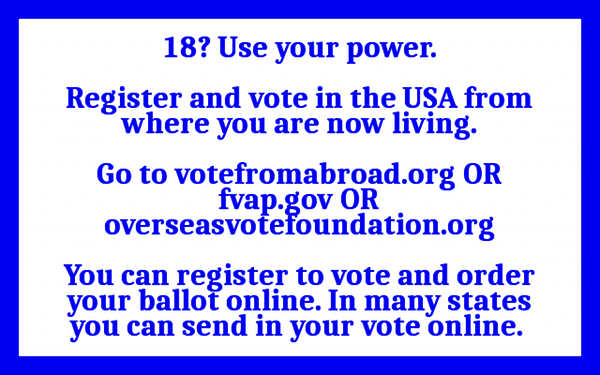

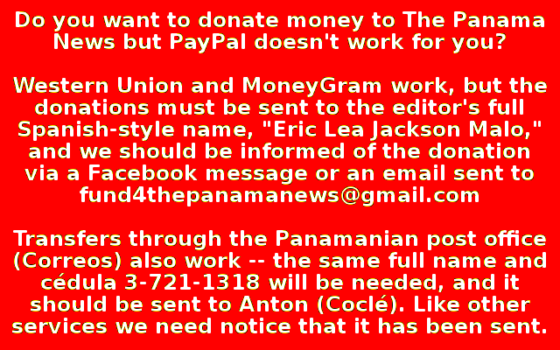

These announcements are interactive. Click on them for more information.