Little transparency about

a spike in newborn deaths

by Eric Jackson

On July 4 the chief physician of the Arnulfo Arias Hospital Complex’s neonatal ward sent a note to the medical director of that institution. In it she complained of the ward’s “collapse,” of necessary medicines and supplies unavailable, of overcrowding that had babies doubled up in single incubators, of not enough monitors, of short staff, of patients out in the hallways for lack of space. There was no response, but in the meantime the medical director of that time, Ahmed Vielgo, left that post.

Then, early in August sources from the hospital complex began to tell reporters that July had seen an usual spike in newborn deaths. That prompted a response.

On August 8 the Social Security Fund (CSS) came perhaps as clean as it will, responding to the reports with an admission of 21 newborn deaths in July. That’s more than double what the institution says has been the norm, but there were suggestions that because many of the babies who died were premature that might have something to do with it. Later, when pressed about the early July note a CSS spokesman declined to say what the problem was but assured the public that it had been corrected, whatever it was.

The overcrowding that doubles up kids in an incubator is a terrible infection risk, but here there is no claim made of any infectious disease spreading. The hospital complex has had its deadly contagions, but this apparently was not one of those.

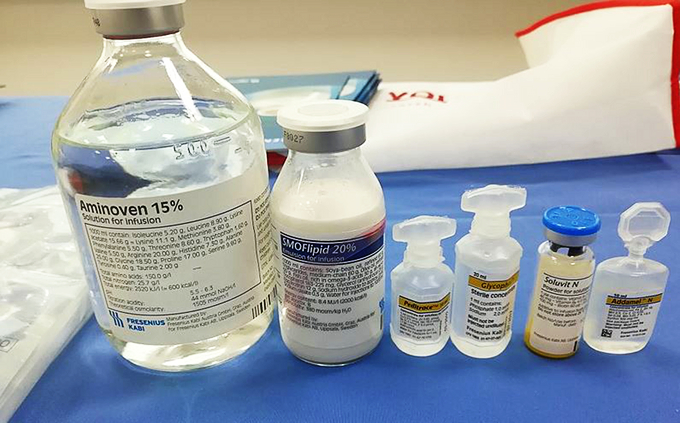

But what specific supply was said to be unavailable for the newborn ward? It was the lipids, fatty acids that are essential to the diet of somebody being fed through an IV or feeding tube. Newborns were being fed a solution without lipids. So far it has not been made public how long the young patients being fed this way went without.

Misdirections, true or false assignments of blame, are the ordinary traps for reporters in such cases. Impunity for people at fault based on their rank, family or race is pretty common too. Accountability in any of Panama’s licensed profession, or for administrators in any of Panama’s public institutions, is rare.

Fernando Castañeda, speaking for the COMENENAL, the joint bargaining committee of the public sector physicians’ unions, blamed it on the administration and, citing the warning not that was revealed only in mid-August, said that “there is a lie — there was a crisis and supplies had run out. From management, we get the response that everything is under control, and no word of any investigation as to what the problem was or is.

~ ~ ~

These announcements are interactive. Click on them for more information.