50 years ago Panama made an acute turn

by Eric Jackson

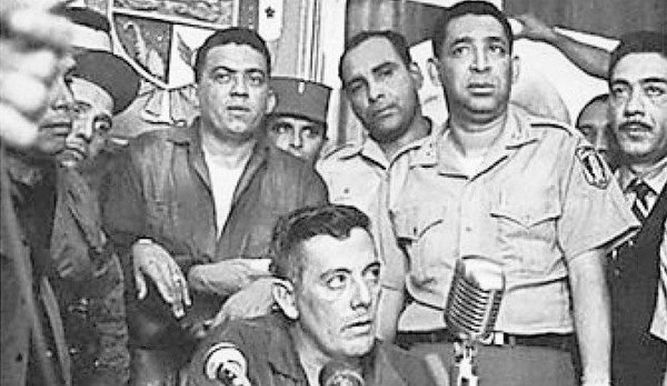

On October 11, 1968, with a recently inaugurated President Arnulfo Arias taking in a movie, Guardia Nacional officers led by Colonel Boris Martínez and Colonel Omar Torrijos politely and unofficially 0shoved aside their superior, General Bólivar Vallarino, and announced the overthrow – once again – of Dr. Arias.

This was not any particularly ideological coup, but it was an event set in a period of world history and a peculiarly Panamanian context. The precipitating reason was the announcement by Arias, who had been sworn in that October 1, that he would reshuffle the promotion schedule for the Guardia Nacional, at the time Panama’s combined military and police forces.

Vallarino was the last of a breed, the product of a former policy that reserved the Guardia’s upper ranks for members of Panama’s aristocratic white families. But he was also successor to and bearer of the torch of José A. Remón, the Guardia commander behind many a coup – particularly several against Arias – and progenitor of a strange social reforming militarism that was previously politically aligned with fragmented remnants of Panama’s Liberal tradition.

Remón’s nemesis, however, was the faction led by the two Arias brothers who became presidents, Harmdio and Arnulfo, was also one of the Liberal fragments. The ancestor of what is today’s Panameñista Party was born in the late 20s as the Accion Comunal movement, a racist formation of young middle class white men who sometimes dressed in Ku Klux Klan robes and advocated the expulsion of West Indian blacks, Sephardic Jews, and in general anyone tracing roots to Asia or the Middle East from Panama. When they put on their suits and played moderate politician – or in Harmodio Arias’s case, attorney member of the Canal Zone Bar – they said that they didn’t have anything against anyone of another race or religion but had to defend Panama’s Spanish language and culture.

The first big run-in between the Guardia and Arnulfo Arias happened in 1941, the year in which a new constitution that stripped West Indian blacks except those from Spanish-speaking lands, the Chinese, the Hindus, the Arabs and the Sephardic Jews of their Panamanian citizenship, even if they, their parents and their grandparents had all been born here. Arias was also playing balance of power games between the USA of Franklin D. Roosevelt and Arias’s personal friend from his years as a diplomat in Europe, Adolf Hitler. The US Embassy and Remón connived to remove Arias from office when the latter took a trip to Havana for various appointments in October of that year. Thus the United States got what it saw as a dangerous annoyance out of the way as it slid ever closer to war with the Axis powers.

If Arnulfo Arias had a friend in Der Führer, Remón had one in Ike. After World War I Dwight D. Eisenhower was stationed in Panama, where it is said that he began his education in earnest as an administrator. He also got to know all segments of isthmian society, including the Guardia officers. Ultimately Remón emerged from the barracks to put on a suit and ran for president. He was elected, by most accounts fair and square. Assassins cut short his presidency but before that happened he made the Remón-Eisenhower Treaty that began a long process of transformation that ended the old Canal Zone.

The traditions and factions survived the crime – still officially unsolved, as to its intellectual author – and by early the Panameñnistas gained the upper hand in the National Assembly to impeach Liberal Marcos Robles, only to have the Guardia step in and overrule the legislature. Arias won that year’s election but lasted only about a week and a half in office.

So, October 11, 1968 – just another Panamanian coup? What would be so special about that?

It led to a generation of dictatorship that only ended with the December 1989 US invasion, a period that brought great changes to Panama’s relationship with the United States and positions in world politics, a time when the solid grip of a few families over Panama’s economy and politics was shattered if not destroyed.

There were intra-military power struggles at first, wherein Boris Martínez was put on a plane to the United States, the G2 intelligence chief whom Omar Torrijos called “my gangster” – Manuel Antonio Noriega – fended off an uprising and Torrijos became supreme leader of Panama from 1969 until his death in a 1981 plane crash. In those years Panama got the constitution that we have today, albeit with a few amendments. We got the 1977 Torrijos-Carter Treaties that ended the Canal Zone and, after a long phaseout, the complex of American military bases there. We were left with one of our major political parties, the one that Torrijos founded the Democratic Revolutionary Party (PRD).

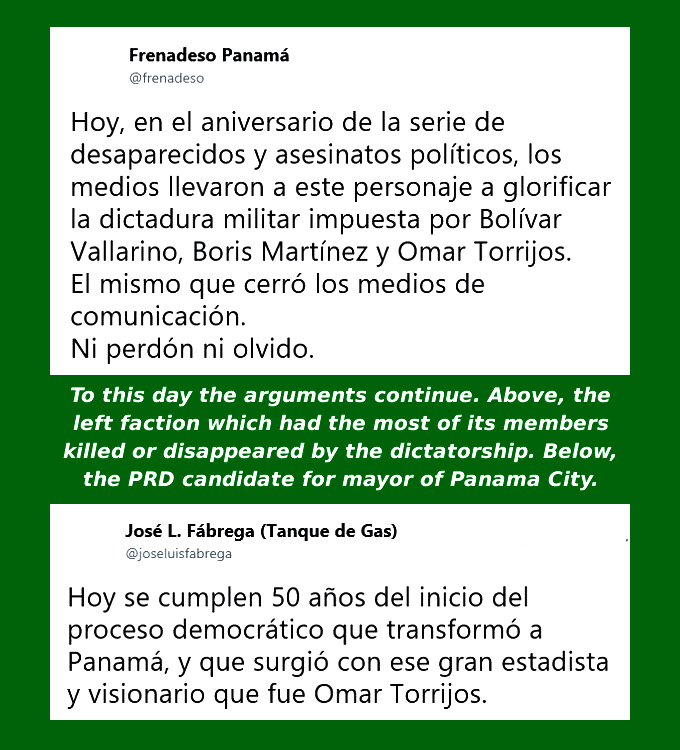

The arguments over the nature of the regime created by the October 11, 1968 coup continue. There were the slain and disappeared, a body count of more than 100 dissidents. There were the busted up monopolies. There was and is a political patronage systezm as a matter of constitutional law. The Colon Free Zone grew and thrived, and great fortunes both licit and illicit were made.

The arguments have been left less informed than they ought to be for two main reasons.

The first, the internal one, is that the Guardia closed and censored the media, purged academia and replaced it with a tawdry political patronage system and fostered a culture of fear. What ought to be the public record was censored and falsified by the military regime.

The second, the external reason, was that in the 1989 invasion the US forces took all the Panamanian government records and with exceptions like the vital statistics and voter registration data at the Electoral Tribunal and the Social Security Fund’s medical and pension records carted the public archives off to United States where they have been kept locked away to this day. Those records would have told us, for example, about post-invasion public figures who had quietly collaborated with the Noriega regime.

Especially guarded by the United States are the full stories of US dealings with Omar Torrijos and Manuel Antonio Noriega, two complementary partners but very different sorts of men. In common they were both CIA informants on their way up. In common they both had their moments of saying no to Uncle Sam. Torrijos was the hard-drinking, gregarious man who very much wanted to be in control but wanted to be loved and cared about how he would be seen in the historical record. Noriega was the much darker character, the spymaster and psychological warfare expert – something he learned from US Army instructors – a man without much of an internal capacity for self-control but who until close to the end had an older brother, the first out gay diplomat in Latin America, whose advice would perform that function for him. The created a generation with certain civic values that just didn’t function, which is why Panamanians in the end let American troops end the dictatorship and never since then got around to some of the necessary corrections that a functional democracy would need.

So the arguments continue, often with more heat than light, as the very real if seldom advertised consequences of the October 11, 1968 coup still surround us.

~ ~ ~

These announcements are interactive. Click on them for more information.