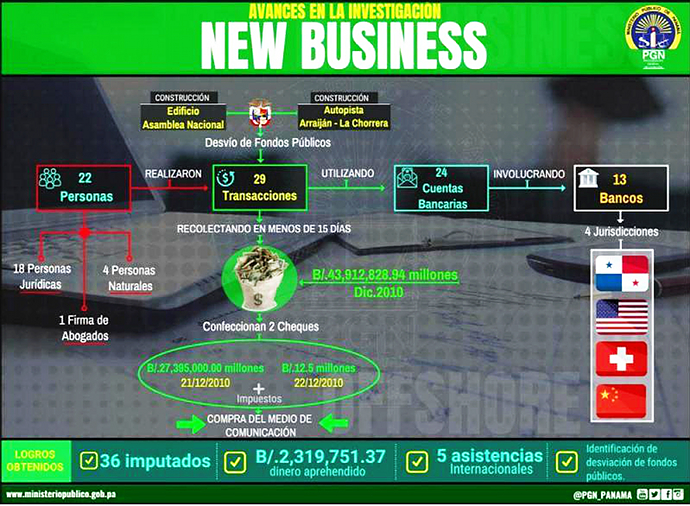

Prosecutors’ chart of the New Business case, for which a court just granted another one-year extension to investigate. Much of the time problem is that this was a crime spread around multiple jurisdictions, requiring proceedings to secure the cooperation of foreign governments. Perhaps a bigger risk to the former president that possible prison time is the possible loss of EPASA, the publishing company that puts out La Critica and El Panama America and a key part of the Cambio Democratico political operation. It is alleged that two major construction projects, the widening of the Arraijan – La Chorrera Autopista and the office tower on the legislative palace, were used for overpayment of public funds, which were then kicked back for Martinelli, hiding behind associates, to buy the newspapers.

Prosecutors outline Blue Apple

and New Business cases

by Eric Jackson

Jailed former president Ricardo Martinelli is running for mayor and legislator from his prison lodgings in El Renacer near Gamboa, looking forward to a February 4 bail hearing and a March 12 trial for illegal eavesdropping, illegal use of government equipment to do that and ultimately the theft of that equipment.

(Full disclosure: as this reporter’s attorney and someone whose work is occasionally featured in The Panama News was on Martinelli’s known 150-member enemies list, email and telephone communication between that person and this reporter were intercepted.)

Before the trial was removed from the Supreme Court the prosecuting magistrate asked for a 23-year prison sentence and the magistrate acting as judged reduce the potential incarceration time to 21 years. Ricardo Martinelli may spend the rest of his life behind bars, or his remaining years out on bail and stuck in eternal litigation. As he fled the country to evade arrest, in any normal legal system bail would be out of the question but this is Panama.

Meanwhile the ex-president’s two sons, Ricardo Martinelli Linares and Luis Enrique Martinelli Linares, wait under house arrest in a Miami mansion for a March 4 immigration hearing, at which they may be deported for being in the United States without proper visas. That sort of deportation would avoid all manner of extradition issues, but the two young men might try to get voluntary departure to somewhere other than Panama so as to complicate and prolong matters.

On January 31 prosecutors from the anti-corruption and organized crime offices laid out their theories of two complicated cases involving the Martinellis. One, the Blue Apple affair, is about generalized corruption in public works contracting during the 2009-2014 Martinelli administration.

Anti-corruption prosecutor Aurelio Vásquez told of a more than $78 million kickback and money laundering scheme, involving a suppose factoring business called Blue Apple, 61 individuals, at least seven construction firms, at least 20 shell companies, the two younger Martinellis, a former minister of public works and the contracting director under him, a former vice president of Global Bank and an attorney who allegedly set up at least six money laundering chains.

Organized crime prosecutor David Mendoza described a scheme to divert nearly $44 million from a major road project and a big addition to the legislative palace, to finance the purchase by a group controlled by Ricardo Martinelli of EPASA, the parent company of the daily newspapers El Panama America and La Critica. The New Business case is named after one of 18 business entities, along with a law firm and four individuals, who funneled the stolen funds through 24 bank accounts at 13 banks situated in four countries. There may be more players to be discovered yet as prosecutors take their discovery missions to Switzerland, the United States and China, plus some Caribbean lands where some of the companies were registered.

The stakes are possible years in prison for the three Martinellis and their accomplices — powerful incentives for partners in crime to turn state’s evidence — and also the Martinelli media empire and its political effects. So far a number of people have made plea bargains but most of those named in both cases are denying all.

What to do in Panamanian legal culture? Why, argue procedure. The former president’s defenders are arguing the doctrine of specialty, which has it that a person extradited for one thing can’t be tried for another crime committed before the extradition without being first afforded an opportunity to return to the jurisdiction from whence he or she was extradited. It is specifically provided for in the 1904 US – Panamanian extradition treaty:

ARTICLE VIII.

No person surrendered by either of the high contracting parties to the other shall, without his consent, freely granted and publicly declared by him, be triable or tried or be punished for any crime or offense committed prior to his extradition, other than that for which he was delivered up, until he shall have had an opportunity of returning to the country from which he was surrendered.

However, as noted in a 93-page opinion by Magistrate Edwin Torres, the extradition was not based only on that treaty, but also on the Budapest Convention on Cyber Crimes and the United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC). Neither of those agreements contain a specialty clause. Nor did the US State Department specify that the extradition was only for the purpose of trial on one of the many cases pending against the older Martinelli.