President-elect Cortizo at the May 8 installation dinner of the new officers and board of directors of the Panama Chamber of Commerce, Industry and Agriculture (CCIAP). This is one of the main groups spearheading the demand for passage of a set of constitutional changes that they have not had the courtesy to publish. Photo from Mr. Cortizo’s Facebook page.

He says that he wants what the business groups want, whatever it is. Can he get it?

by Eric Jackson

How did we get here?

Panama lives under the dictatorship’s constitution. The old Guardia Nacional stepped in on October 11, 1968, to overthrow President Arnulfo Arias — again. This time the precipitating event was that the president who was sworn in that October 1 announced that he would be altering the order of promotions for the combined military and police forces. Arias was notorious racist and back in the 40s and 50s his nemesis José A. Remón broke down the racial and class entry barriers to the officer corps, such that by 1968 a darker cast of characters has risen to its penultimate heights. More than anything it was a job action, but the troops did away with a constitutional order that had upheld a “government of cousins” that few who were not related missed.

The coup came at a sensitive time, when talks about the future of the Canal Zone and the Panama Canal were underway. Something approaching a final deal was almost at hand, but when the old order was discarded that was put on hold as well. It was not until a few years later when the two coup leaders, Omar Torrijos and Boris Martínez, had a falling out that was decided in the formers’ favor via more than anything else the intervention of the intelligence (G2) chief, on Manuel Antonio Noriega. With Martínez exiled to the USA Torrijos had to figure out a strategy to deal with the Americans.

The old order’s election cycle became a time constraint. For the consumption of the US public and politicians, some democratic institutions needed to be built or rebuilt to show off abroad. Not that the general staff was about to give up real power, of course, but there was a need for some fig leaf of of legitimacy. So the representantes — more or less city council members with more executive and distributive functions than their counterparts in most other countries — were convened for a 1972 constitutional convention. What emerged was a military regime with elected local officials and an elected legislature, but with those politicians who played along given resources to distribute among their constituencies. There would be legal political parties, which were given the power to remove those elected on their tickets if they sold out and didn’t toe the party line. Men in uniform appointed the civilians of the executive branch.

It was good enough to get a 1977 agreement with the United States. Then, in 1981, General Torrijos died in a plane crash.

WHAT? Caudillos don’t live forever? Succession had not been contemplated. So in 1983 the first patch was applied, wherein there would be a direct popular election of the president. That was held in 1984, and stolen from Arnulfo Arias by General Noriega. The military still held the power and, after the death of Noriega’s mentor and older brother in 1985, was used and abused ever more erratically. That Uncle Sam was demanding over Panamanian support in the Contra War against Nicaragua complicated things.

There came the Noriega crisis, with crippling US economic sanctions, a 1989 election that the military could not win and thus tried to annul, then increasing hostilities leading up to the 1989 US invasion that ended the dictatorship. The 1972 constitution was kept, but patched four more times.

So what is it now? Multiple corruption scandals in the judicial, legislative and executive branches. High public debt and pervasive public institutional dysfunction. An economy that looks good by fudged figures but not to working people, in which the canal and the banking sector may be doing well enough but in which agriculture and industry are hardly producing anything. With almost all legislators stealing from the public treasury and the courts an international embarrassment, time for what? Another constitutional patch.

CoNEP contemplates constitutional changes. From a CoNEP photo.

This time around…

Two of the country’s main business groups, the National Private Enterprise Council (CoNEP, mostly big business with which the government will directly deal), and the CCIAP, began to formulate constitutional changes about a year ago. This they did in consultation with the United Nations Development Program (UNDP).

You might think of peacekeepers, the World Health Organization or UNICEF feeding hungry children when you think of the UN. However, the UNDP is the point organization for neoliberal policies in the less rich countries. In Panama their advice has included privatizing public pension programs, cutting instruction in civics, history and the arts in the public schools and cutbacks in public health care programs.

Last August and September, CoNEP and the CCIAP began to describe what they were thinking about in terms of constitutional changes. One matter was the way that the Supreme Court is selected and organized. They were for raising the minimum age to become a magistrate from 35 to 45, extending the terms from 10 to 20 years, and instead of presidential appointments creating a nine-member panel representing “civil society” to come up with a vetted pool of potential appointees, who would have to be approved by a two-thirds vote of the legislature. Were the president’s choice to be rejected the sitting magistrates would appoint a temporary jurist while the politicians couldn’t make up their minds?

Civil society? In Panamanian reality, that means rich white people not holding any public post at the moment. As it was described last year, representatives of business organizations, organized labor, non-governmental organizations, civic clubs, academia, the nation’s main bar association (the Colegio de Abogados) and people designated by the president.

WHICH businesspeople? Certainly not those of the 40% of Panama’s work force who are in the informal economy. Certainly not the Chinese-Panamanian merchants who vastly outnumber the members of CoNEP and the CCIAP combined. And you can reasonably estimate which sorts of clubs and non-governmental organizations the business groups have in mind.

There were also proposals floated about changing the way the legislature is selected and operated. Suggestions of a bicameral legislature with nationally elected senators were made, and others of at-large deputies taking seats in a National Assembly of reduced size. There was not any talk about getting rid of the anomalous multi-member circuits and the odd results that come from that, but lots of talk about fewer legislators in all, as if fewer politicians means less corrupt government.

In the middle of last December when nobody was paying much attention due to the holidays, we were told of a unified CCIAP – CoNEP constitutional proposal, to be passed by way of a vote by the present legislature and then by the new one in keeping with Article 313 of the Political Constitution of Panama. The proposal was submitted to the government. But neither the government nor the CCIAP nor CoNEP has ever published the thing for any citizen to see. Nor have any of the media who were told about this proposal published it.

Varela objects. President Varela ran for office in 2014 by promising a constitutional convention, but then said that he couldn’t control the outcome so reneged. In response to the business groups’ plan, he proposed to add another item to the May 5 ballot, a referendum on whether a constitutional convention should be called. CoNEP and the CCIAP said that it was too late in the game, that no distraction from their undisclosed document should be allowed.

And the National Assembly, which has been feuding with the president, killed his proposal. And did this and that and complained how horrible and illegal it was for the Comptroller General to say that they stole. And let the last regular session of this legislature end on April 30, without any action on the CoNEP – CCIAP proposal.

Can’t let THEM in on constitutional reform! Some don’t even know the banking district. Electoral Tribunal photo.

For Cortizo, the math is the easier part now

In the recent election campaign, the number one and number two finishers in the presidential race both said that they supported both the business groups’ proposal and the preferred method of passing it. That could still be an arithmetic problem if enough of the deputies who didn’t run for re-election or who ran and lost don’t attend and don’t send their suplentes in their stead. No matter what Rómulo Roux said, some of the CD caucus might still be indisposed to help Nito Cortizo get anything that he wants. But there have historically been ways to persuade disgruntled lame duck legislators.

The problem for Nito and the business lobbies is in the person of Juan Carlos Varela and in the provisions of Article 149 of the constitution.

The current legislature’s regular sessions are over. They can only act in a special session. And Article 149 says that only the president calls a special session, sets the time and place and specifies the subject matter. The National Assembly can’t take up any business that’s not on the president’s call.

Lawyers might argue. They might say that Article 313 provides that the legislature may start a constitutional process of their own volition, without the president’s or anybody else’s permission. Most probably, though, that would have had to have been in the regular sessions.

But what if Varela convenes them to ratify some contract and they do that, adding constitutional reform as an amendment? It’s probably not proper for a bunch of reasons, but nobody really knows what our politicized and dysfunctional Supreme Court might say.

Most probably Cortizo has an electorate of one to convince if he wants to advance the scheme — Juan Carlos Varela.

But anyway, WHAT IF constitutional reform comes as an amendment to some other business?

Then surely the text of what the next legislature passes wouldn’t be exactly the same. It’s OK for the new legislature to vary the wording of the previous set of deputies. But in that case Section 2 of Article 313 provides that any constitutional amendment passed in that way has to be ratified by the voters in a national referendum to be held within six months.

Would Cortizo want to risk the wrath of an electorate that thinks that a fast one was being pulled on them at such an early point in his term? The critics are already lined up.

Most probably a Cortizo presidency does not see any constitutional reform until much later, either in light of an acute crisis or as business to finish as the term is ending.

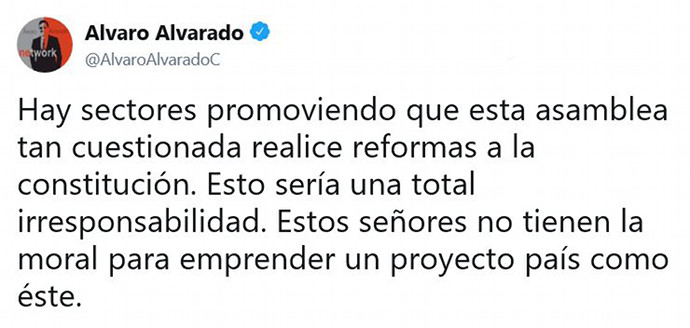

A roughly translated tweet by noteworthy television pundit Alvaro Alvarado: “There are sectors pushing this very dubious assembly to carry out reforms to the constitution. This would be totally irresponsible. These men have no right to undertake a national project such as this.”

These links are interactive — click on the boxes