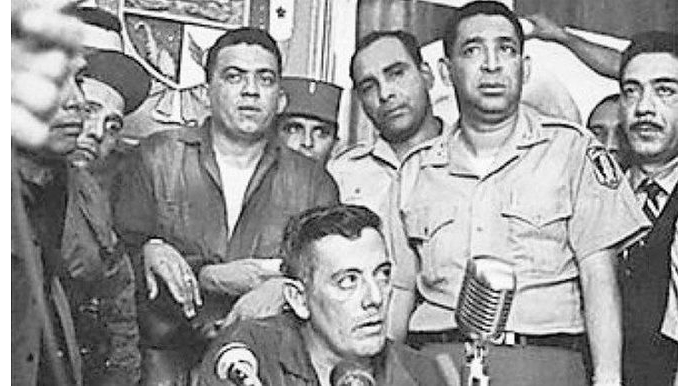

Omar Torrijos Herrera, the son of a Veraguas school administrator of Colombian origin, speaks into the microphone that evening to announce a change of government.

October 11

by Eric Jackson

If you look at the PRD flag, the circle with the number 11 is no mere geometric pattern – it’s the letter “O” to go with the numbers, signifying October 11, 1968. On that day up-and-coming officers of the Guardia Nacional, at the time what they called Panama’s combination of military and police forces, staged an uprising that first appeared at the barracks in La Chorrera but quickly caught on and sent Dr. Arnulfo Arias, inaugurated president for the third non-consecutive time 11 days before, fleeing across the largely unmarked boundary to the Canal Zone with his young secretary and mistress, Mireya Moscoso. Then off with them to Miami and Madrid, but never quite gone from the hearts and minds of many Panamanians – for better and for worse.

At the end of the day, general and Guardia commander Bolivar Vallarino, who was on his way out anyway, was history. It was not, however, as it Vallarino had been taken entirely by surprise. He had been involved in the coup plotting from the outset, or nearly so. As were some prominent civilians like the broadcasting mogul and former foreign minister Fernando Eleta and attorney and Johnson-era canal treaties negotiator Roberto Alemán. But Vallarino’s consultations, with his scheduled successors in the Guardia present, had taken place in August, between that May’s elections and Arias’s October 1 inauguration. Those talks to prevent another Arias presidency came to naught, except that even if word got not much farther than the little group that was involved, feelers had been put out and those present must have from that process gained a sense of who would tolerate what.

The morning of the 11th, Guardia commanders learned that Arnulfo Arias intended to alter the Guardia promotion schedule an install a civilian friend as head of the Presidential Guard. At the end of the day, atop of the new military junta two men presided, Omar Torrijos and Boris Martínez. It wasn’t a sudden decision to act, but Arias’s move made time of the essence in the eyes of the officer corps.

Vallarino, with Torrijos and Martínez by his side, may have conducted his earlier consultations with notables, but the two subordinates organized the “Combo,” a conspiracy involving most of the second, third and fourth-string officers in the various security agencies, not only in the Guardia but including the Presidential Guards. Why such near unanimity among the troops? It was because the soldiers had word that Arias intended to first break up the Guardia’s promotion schedule, and rumor had it eventually the Guardia itself. Careers were on the line, there was bad blood between Arias and the Guardia from previous bad experiences – like the two prior coups in which the physician turned racist demagogue had been overthrown, and the various fingers on election scales to otherwise keep him out – and because Vallarino was the last of a breed, the Guardia commander from “a good family” from the days before Arias’s nemesis, Guardia commander and martyred president José A. Remón, broke up that snobbish barrier and opened the officer corps to bright young men of more humble origins and whatever race or complexion.

Uncle Sam might have intervened – the Americans were rather fully informed and its forces were all there to step in had that been the preference – but the US ambassador at the time, Charles Adair, had advised his superiors at Foggy Bottom that Washington should stay neutral in the brewing confrontation between Arias and the Guardia.

The US Southern Command had a liaison officer assigned to Torrijos, then a lieutenant colonel, and as the leading lights of the Combo set out with weapons ready for their agreed tasks, the American soldier asked Torrijos what was going on, he was told “A coup d’etat, stupid.” The liaison officer asked to make a phone call but not only was that denied him, they put him under guard in a room at the Comandancia with a bottle of whiskey to keep him company.

These were Cold War times, and almost all of the officer corps had been trained by, given favors by, cultivated by and vetted by US military and intelligence agencies. The School of the Americas was at Fort Gulick, not far from the Gatun Locks, and it was an ordinary part of a Guardia officer’s education.

The man who helped to save Torrijos in later power struggles and whom Torrijos described as “my gangster,” on Manuel Antonio Noriega, head of the Guardia’s / Panama Defense Forces G-2 intelligence unit in the Torrijos years, was trained at the School of the Americas in psychological warfare. He proved to be very talented as messing with people’s heads, and so much of the chess game of the 1989 US invasion and the US signals and provocations leading up to it ought to be understood as an American exercise in messing with Noriega’s head. And indeed, messing with Panama’s head, so much so that to this day one of the things missing in most Panamanian indictments of who and what Noriega was is the item that he was a soldier who deserted his post under enemy fire.

On their ways up the command structure, both Noriega and Torrijos had been CIA assets. The full extent of it is a secret guarded now at Langley, but what leaked out – and likely very selectively and perhaps grossly distorted – were about low rent favors like cartons of cigarettes and bottles of booze for Torrijos.

(VERY bad manners in many a Panamanian circle to say that Torrijos was an alcoholic, but that was the case. Once upon a time it was so with respect to wining Union General and the president who oversaw reconstruction and the consolidation of the Robber Barons, Ulysses S. Grant. It can also be truthfully said about the United Kingdom’s great wartime prime minister and Nobel-winning historian, Winston Churchill. With each man it’s a matter of some historical importance to look behind the social stigma and consider the patterns and occasions of the addiction. The guy who’s an absolutely brilliant administrator in the morning and then as the day’s refreshment takes hold has an aide to take note of drunken mental tangents and bring up the promising ones in a subsequent sober moment, that’s a classic. So is the one who stays sober when urgent duty calls but gets drunk on his ass when on private time he considers the issues of his personal life. On October 11, 1968, and later in the key moments of Panama’s decolonization process, Torrijos was very much in control of his faculties.)

Don’t fall into the dubious connection of associations’ dots and interpret the October 11th coup as a matter of American AGENTS taking over the Panamanian government. It was a matter of occasional US intelligence ASSETS doing what they thought they needed to do to protect their institution and their personal careers. It was a coup without a particular ideology or political or geopolitical alignment, let alone a program of action, in mind. Many details were left to be sorted out.

One of the details to finesse was who would lead, and what comes to us is generally from self-serving accounts and winners’ impressions, but in any case what happened was that there were various power struggles within the Guardia and in March of 1969 Martínez made his move with an economic program that alienated the junta’s civilian ministers running government departments but which several top commanders liked. But in the third and below strings of Guardia leadership Torriijos was far more popular and Martínez was put on a plane to Washington with several other officers and an appointment as Panama’s representative to the Inter-American Defense Board. Martínez got off the plane in Miami and abandoned his military career and involvement in Panamanian public affairs.

Were there really that many details to iron out with respect to the Canal Zone’s fate? Yes, Omar Torrijos and Jimmy Carter signed the treaties in 1977, but something similar had been before the Johnson and Robles administrations in 1967 before domestic issues in both the United States and Panama set that process aside for a moment. If the truth is to be told, both the Guardia and the Pentagon brass had pretty much agreed that, whatever the immediate demand for bases, that segregated enclave of Americana – about two-thirds of the civilian population mostly blacks of West Indian extraction and non-citizens of the United States and the other civilian third mostly white US citizens – was disposable. Dwight D. Eisenhower had been stationed in the Canal Zone in the 1920s, knew both Canal Zone and Panamanian society well, got along famously with general and the president of Panama Remón, and set a slow-motion process of US devolution of the Canal Zone on its course. But it was still a dicey matter on the American end – the treaties were only ratified by one vote in the US Senate, and then only after addition of the humiliating DeConcini Amendment.

Both to shore up the Panamanian consensus so that no dissident wedges might derail the treaty process and to impress the Americans with Panama’s unity, Torrijos oversaw a number of social truces. A labor code that legalized union was passed. Ordinarily business leaders would have sternly resisted, but the left wing of the labor movement that would have said it wasn’t enough was at the same time hunted down and some of its leading activists disappeared. Senior positions in the government’s civilian bureaucracy were no longer de facto reserved for white people of the “better” families. Private monopolies like the old metro area bus company were busted up or nationalized. The Colon Free Zone and the Panama City banking sector were allowed to flourish without the same old families claiming dibs on anything that makes money in Panama. The public sector expanded to the advantage of Panamanians on the lower end of the economic hierarchy. A lot of leftists were co-opted into the Democratic Revolutionary Party (PRD) that Torrijos founded. A constitution based on political patronage perks for those civilian politicians who cooperated with the regime was jammed through and with a few patches remains with us to this day. The general called it the “Revolutionary Process” even if there were revolutionaries who called it anything but.

In 1977 the treaties were signed and in 1979 they began to take effect. The old social truces began to break down. Torrijos’s drinking and behavior seemed to be affected by that. One change was said to be the risks that he’d have his pilots take when flying around the country. One day in 1981, in a driving rain, the pilot tried to land at the rural airstrip in Coclesito, had to abort and while pulling up to circle around and make another attempt, clipped a treetop with the DeHavilland Twin Otter’s wing. When the wreckage was found there were no survivors.

Four agencies from Panama, Canada and the United States investigated the crash and came to a common conclusion. Was it a convenient cover-up for all? Surely someone would have come forward by now if that had been the case.

Yet the conspiracy theories persist because by 1981 Panama, the United States and the world were in different paradigms than those prevailing on October 11, 1968. There have been big changes on all of those fronts in the decades since Omar Torrijos’s death. The crash in Coclesito was a convenient event with which historiographers could punctuate the timeline’s continuities and disjunctions.

Today’s PRD members and factions will lay claim to or dispute the meanings and history of “Torrijismo.” Reasonable enough. Omar Torrijos and the October 11 coup are no mere figments of imagination. Complicated as the man and the event really were, they have left indelible prints on what Panama has become since. Even if the national and international substrates on which those prints were left has been stretched and cropped on multiple occasions over the years. October 11 still matters here.

Contact us by email at fund4thepanamanews@gmail.com

These links are interactive — click on the boxes