What? Some burnout forgot to buy booze YESTERDAY?

Photo from a Colombian voter’s Twitter feed.

Argentines, Uruguayans and Colombians go to the polls today

by Eric Jackson

There is this backdrop of political, social and economic unrest across much of Latin America. Leave it to some wag from afar to write about a “Latin American Spring” and miss all of the nuances of different countries with different histories and economic lives. A real common factor is a weak global economy that affects different places in different ways. In many instance the unrest has in common external forces — the World Bank and International Monetary Fund demanding austerity and Washington trying to overthrow leftist governments are the biggies there. And then there are the common maladies of the region’s political castes — personalism expressed in leaders’ “sure knowledge” that a country can’t get along without its caudillo, family political dynasties, jaded political parties that stand for nothing much more than jobs and government contracts for their members. Ah, well — the time has come to vote and South Americans are doing that.

Argentina: a likely end to an interregnum that went badly

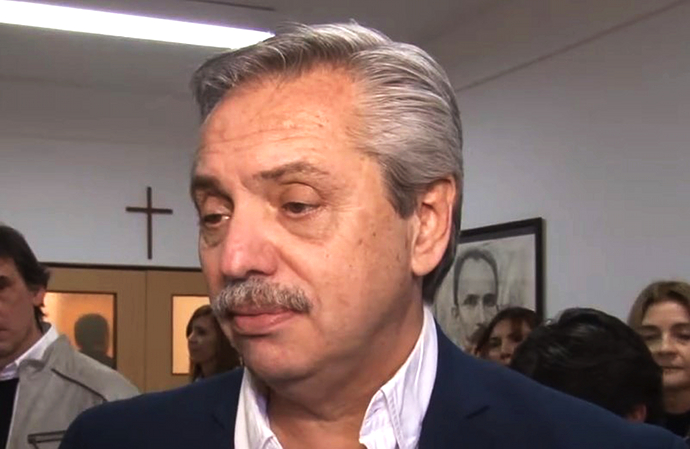

Argentine front runner Alberto Fernández barnstorming for the student vote. Photo by UniRio TV / Universidad Nacional de Río Cuarto.

Acclaimed as capitalism’s model answer to Latin America’s turn-of-the-century “Pink Tide,” Mauricio Macri came to power in an Argentina tired of the scandals and banality that are the usual ruts of Peronist governments that have been in power too long. Since the middle of the 20th century the political tradition of General Juan Perón — populist, corrupt, nationalistic, all over the map with respect to economic and social policies — has been Argentina’s default choice.

After a period of failed rightist economic policies under the Justicialist Party (Peronist) president Eduardo Duhalde, the more democratic socialist oriented governor of Santa Cruz province, Néstor Carlos Kirchner hijo, came into office in 2003 along with his then senator spouse, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner. The Kirchners’ administration paid off the debt to the International Monetary Fund, with which it made a debt swap deal, and defaulted on a bunch of other debts. The austerity policies and currency peg to the US dollar — IMF ideas, by and large — were abandoned and a collapsing economy was more or less revived. They had to officially lie about the inflation rate to get away with some of this. Néstor Kirchner didn’t seek a second term, but instead first lady Cristina Kirchner — known to Argentines as CFK — ran and was elected president in her own right in 2007. She was re-elected in 2011, but Argentine exports stagnated and real scandals about graft and money laundering by administration figures and allegations that are probably exaggerated about covering up Iranian involvement in a 1994 terrorist bombing of the main Jewish community center in Buenos Aires dogged CFK’s government.

She didn’t run again in 2015, and her preferred candidate was defeated by the rightist mayor of Buenos Aires, Mauricio Macri.

Macri embarked on a series of prosecutions of CFK and people in her administrations, and embraced the IMF economic policies that the Kirchners had left behind. There were a bunch of convictions, including of a Ministry of Public Works official in her administration hiding bags with millions in cash in a monastery. But CFK had immunity as a senator and investigations of improper dealings with Iran and money laundering through Kirchner family hotels were and are stalled.

Also stalled has been the Argentine economy under Mauricio Macri. That’s the big problem for him and the likely lesson that will be taken across the region. Austerity politics that enhance social inequality are toxic to political careers.

All the polls have it that he is set to be crushed in his bid for re-election by the Peronist ticket of Alberto Fernández, the former presidential chief of staff, with CFK as the vice presidential running mate.

Uruguay: generational change and maybe the end of a leftist period

Luis Lacalle Pou and Beatriz Argimón are likely to finish in second place in today’s voting in Uruguay, but they are slight favorites to be the next president and vice president respectively after a November 24 runoff. This would end a 15-year leftist hold on the country’s presidency. Lacalle, the son of a president, is promising that there won’t be wrenching social changes. He is, however, promising economic shock therapy to deal with the national debt. Wikimedia photo by Fadesga.

What happens when an older generation starts to die off, and there is a demograhic bulge of adolescents and young adults?

One thing is a crime wave, of offenses that young men commit, generally against one another, until they tend to grow out of that phase or get removed to prisons or graveyards. Fluctuations in crime rates are a favorite subject of demagogues, but usually they have to do with one or both of two things: at the end of a war there veterans who can’t turn off the violence to which they had been conditioned, and a simple population change that has more adolescent boys and young men in the mix.

Uruguay did have a vicious 11-year dictatorship, with urban guerrilla warfare during and preceding that, but it hasn’t been the place of returning veterans in a long time. But there are demographic changes that have expressed themselves in record homicide and armed robbery rates. There is a package of “get tough on crime” measures in a referendum on today’s Uruguayan ballot and that’s expected to generate interest and turnout on the right wing of the spectrum. But the candidates of the incumbent Broad Front (Daniel Martínez) and the center-right National Party (Luis Lacalle) both say that they will vote against it.

Another thing that happens with generational change is that new electorates with new concerns emerges. The ghosts of the dictatorship and the people it disappeared, and the later fond memories of leftist elder statesmen who are still living and who ran credible democratic administrations are not all that impressive to voters who remember nothing else. Polls show that a lot of Uruguayans are ready for change after 15 years of the left.

The left is going to win the first presidential round today. The biggest questions are about what happens in local, regional races and with the composition of the national legislature.

Will predictions for the November 24 runoff hold through then? Maybe not. First of all, there will be no crime referendum then. Second, people may look at today’s down-ballot results and seek to balance them out. Uruguay, the historic buffer zone between Brazil and Argentina with its jaded skepticism about both and its highly educated population, has historically been big on political balances.

So, with several countries in the region having ongoing or recent turmoil sparked by austerity measures, will the runoff issue shift from crime to bread and butter? And how will that play across the fertile pampas of Uruguay? Stay tuned.

Colombia’s local transitions from civil war to the next thing

One of the concentrations of election violence has been along Colombia’s Atlantic Coast, where former paramilitary and guerrilla forces that are reincarnated as criminal gangs get hired as hit men by local power brokers – often “legitimate” wealthy families but with drug lords in the mix — who use violence to control local politics. It’s a problem in other regions of Colombia’s hinterland as well – this is the centrifugal aspect of the country’s political life, where defiant local forces resist norms coming down from Bogota. In past centuries such forces led to Venezuela, Ecuador and Panama breaking off from Simón Bolívar’s Gran Colombia. Photo by the International Crisis Group.

About two dozen candidates have been slain in the campaigning for today’s local and regional elections in Colombia. That’s an increase from other elections since the 2016 peace accord. It’s not, however, a systematic national campaign by any one side. It’s Colombia’s hinterland warlord tradition, in a period without any particularly strong warlords on the scene.

Colombia’s local elections are staggered so as not to happen when the country elects presidents. The norm is that traditional parties and politicians do well in these rounds of voting. Some fraud, and some violence, are also traditions. Some of the city council members, mayors and governors elected today are sure to be challenged in courts over allegations like these.

What’s new and perhaps interesting is what’s going on at the fringes. Will the Greens regroup and resume their stalled growth? Or will they lose supporters to new formations? Will the FARC guerrillas, now an electoral force that calls itself the Common Alternative Revolutionary Force and is running hundreds of candidates, elect any charismatic newcomers to the political scene? Will former Bogota mayor Gustavo Petro’s new party take off? Will identity politics, in the form of indigenous and Afro-Colombian parties, become important phenomena in rural areas?

President Iván Duque’s right-wing government may or may not consolidate itself in the municipalities or regions, but whatever happens it’s unlikely that today’s voting would diminish or much increase his power. Today is important to the shape of what comes after — new faces, new parties, different paradigms.

Contact us by email at fund4thepanamanews@gmail.com

These links are interactive — click on the boxes