Colon was once known as the “Tacita de Oro,” the little golden cup. A lot of money has been made in that city, and a lot is still being made. But the place tends to get sucked dry. It was like this before the latest extraordinary suction, the Odebrecht contract to “renovate” the city. Archive photo by Eric Jackson.

Colon Day: a very Panamanian revolution

by Eric Jackson – cédula 3-721-1318

So, what were the details of Panama’s smashing military victory over the 500 Colombian Army troops stationed in Colon to maintain Bogota’s authority on isthmus?

First of all, understand that most of these soldiers were bored and war-weary, people who had been mobilized for the Thousand Day War that has ended about a year earlier. Second, consider that throughout the war the Conservatives held control of Colon, Panama City and the Panama Railroad route between the two cities.

Politically, this was traditional Liberal turf. It was under Conservative control due to a great Liberal blunder at the war’s outset, an insane charge into machine gun fire on Panama City’s Calidonia Bridge over the Curundu River. There were some 500 Liberals killed in that battle, but many of their weapons were rescued and sent to the Interior, for Liberals to fight another day. That they did, in a civil war that essentially depopulated and scorched Cocle province with Liberal guerrilla general Victoriano Lorenzo grabbing the weapons from the Conservative mayor of San Carlos who died trying to intercept them, leading a retreat to a mountain stronghold northwest of El Valle, then sweeping down to take Penonome and Aguadulce. But Lorenzo had been betrayed, then executed at the Casco Viejo’s Plaza Francia some six months earlier.

The execution of Liberal guerrilla general Victoriano Lorenzo in Plaza Francia on May 15, 1903. Carried out under Conservative auspices after US “intermediaries” had excluded Lorenzo, whose army held Cocle, from peace talks, this execution assured white rule in Panama.

In Colombia the Conservatives had everything rigged but could not muster a quorum for the senate to approve any treaties nor muster the votes in the rump senate to pretend to do so. In Panama City, the Conservatives were politically in a bad way, not because they didn’t rule with an iron fist but because the city’s food supply from Cocle and points west was cut off both by loss of production and by a Liberal blockade. The blockade lifted with the war’s end but those who had fled their farms for the city mostly did not go back and Panama City was starving. In early 1904, when the first US Army medical mission arrived in the city, they found that the leading cause of death was beriberi, a starvation disease.

After the rump of the Colombian senate had declined to ratify a canal treaty with the United States the previous August, things were getting desperate for the shareholders in the moribund but still existing French canal company. Its concession would expire at the end of the year. Thus its shareholders, the biggest of which was the Panama Railroad, would have little or nothing to sell. The railroad company and the local Conservatives needed a new paradigm, quickly.

So a coup plot was hatched, essentially a Panama Railroad and Conservative Party conspiracy, with the connivance of the US government. The new president, Manuel Amador Guerrero, was the railroad company doctor.

The top Colombian military officers were bribed. Orders went out for the next levels of military commanders to take the train from Colon to Panama City for urgent consultations.

They got on the train, and out in the jungle near the Continental Divide the engine decoupled from the officers’ car and sped away. The troops at the Colon garrison were thus left leaderless.

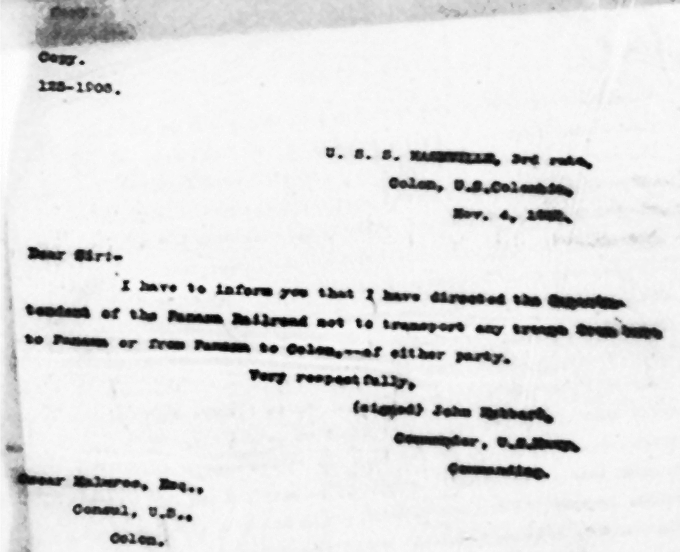

A carbon copy of a note from the skipper of the USS Nashville to the US consul in Colon, telling him that he had directed the Panama Railroad not to transport Colombian troops.

And besides, November 3 was a Colombian holiday. Even though Ecuador had gone its separate way, on November 3, 1820 Cuenca had declared independence from Spain and the Colombians still celebrated it. A boring day for bored soldiers, and the bars, stores and banks were mostly closed. However, the Colon office of the Star & Herald had money in its safe, the publisher, the mayor and those with liquor sales licenses were in on the plot and courtesy of the press all available liquor in town was purchased and delivered to the garrison. The troops got drunk en masse.

By the time that anyone sobered up enough to notice, the USS Nashville had landed and disembarked its Marine contingent. US forces were patrolling the streets.

What were the troops to do? The mayor made a gracious offer. They could get on a ship and sail back to Colombia, with guarantees of no violence or abuse from the Americans or the fine citizens of Colon.

That offer was accepted, and on November 5 the soldiers got on a ship and sailed away.

Thus went the resounding military victory in Panama’s war of independence from Colombia. Colon has celebrated it ever since.

US Marines in control of the railroad company headquarters in Colon on November 5, 1903.

Postscript

Colon had its booms and busts, never more so than in the busy days of World War II. It became one of the capitals of Caribbean English culture, something that promoted racist reactions in Panama that culminated in the 1941 constitution that stripped all Panamanians tracing descent to the non-Hispanic West Indies, the Middle East, Asia or directly from Africa of their citizenship.

But on the eve of World War II, Franklin D. Roosevelt was not about to accept one of Hitler’s friends as president of Panama. Not with ships laden with war materiel for Great Britain passing from the US West Coast through the canal to run into a gauntlet of German U-boats, some lurking right off of the Colon breakwall. A coup was arranged.

The West Indians who found work with the Americans after the canal construction was done in 1914 prospered, relatively speaking. The civilian majority of the Canal Zone population and the Panama Canal work force, they were paid much less than the white Americans. There were jobs to be had on the US military bases, too. The US Army brass – one Dwight D. Eisenhower was stationed in Panama in the 1920s, and Canal Zone governors were always US Army Corps of Engineers major generals – liked the Colonenses. The Pentagon opened up enlistment in the US Armed Forces to Panamanians, especially those who had worked for the canal or the base or the families of such people.

On the Atlantic Side the main West Indian townsite they originally called Silver City, after the pay system by which Americans were paid in gold and all others in silver, but later that became Rainbow City. A nearby shantytown across the boundary on the Republic of Panama side, Follks River, also had an Afro-Antillean flavor. (Folks River is long gone, swallowed up by Colon Free Zone expansion.)

With World War II came boom times, and the seeds of decay. Those folks who enlisted with the American forces mostly became US citizens and emigrated, many later sponsoring family members to move to the States. In 1943, as a US military project, the Trans-Isthmian Highway was built – and became a route for people to move to the capital, for Panama City residents to commute to Colon and back to work, and most ominously for Colon, for a lot of small manufacturing by which that Atlantic Side city was to an extent self-sufficient to be displaced by products coming from the other side.

Later, starting in the 1970s, roads were built along the coasts of Colon, up the Costa Arriba to Portobelo and beyond, down the Costa Abajo out past Rio Indio to Miguel de la Borda. On these roads came poorly educated people, displaced from fishing and farming pursuits. The coastal roads also became important facilities for drug smugglers and police presence was enhanced to do inconclusive battle with that.

Colon languished, and with the notable exception of during election campaigns was neglected at best or disrespected as usual in the halls of power. The big exception to that? The Colon Free Zone. Ordinarily, indolent rabiblancos will see any economic success that someone else who is unrelated has and grab at it. Bribing the government to harass the innovative business has been a favored tactic. But in the Free Zone huge fortunes were made outside of the peripheral vision of the pretentious Creole aristocracy. The Mottas in particular became very rich, too powerful for someone with the right surname to rob with a pen. During the more than 21 years of military dictatorship the illustrious families could also set up shop there but were not allowed to grab what others were building.

But in the Free Zone and in many other Colon businesses, white faces were thought essential for jobs dealing with customers, so a lot of those positions went to commuters from Panama City. There was a bit of money in government, which has seen a multipartisan succession of rapacious mayors, governors, representantes and diputados, who generally put as many family members as possible on public payrolls. Colonenses feel robbed, with justification even if they have elected these swarms of sticky fingers.

So, is Colon going to be saved? Perhaps. There is always the promise of some new project, some new gimmick, some new savior from without. The success stories have generally come from folks relying on their own resources, and have usually had to leave Colon to make their names and fortunes.

One gimmick that has been around for decades is the idea that expanding the Colon Free Zone to encompass the entire city center would bring prosperity there. Mostly, it has sent people from square mile of the low-lying island out to housing projects out on the highway. Land tenure law that prevents landlords from evicting people from condemned buildings and tenants of condemned buildings to obtain the property via squatters rights prompted an arson boom, whereby the buildings would be gone but a child or grandchild of the last person who collected rent would have a vacant lot to speculate with and hopes of the Colon Free Port making that parcel far more valuable.

Finally, progress on that gimmick – a more than $1 billion project, an overpriced no-bid contract with the Brazilian hoodlum corporation Odebrecht to renovate the city center. Without taking into account climate change that down the coast has already made some of Guna Yala’s islands uninhabitable and brings far more frequent flooding into Colon City. Without regard for all of the ongoing enterprises put out of business during construction. It’s yet another misery-bearing boondoggle with a prosperity label and a deceptive price tag.

So on this Colon Day, it’s a population that has a lot of people struggling for survival that celebrates.

Another broken promise, also another thuggish Odebrecht contract – for more than a billion dollars – on which SOMEBODY made a lot of money. Photo by the Varela Presidencia.

Contact us by email at fund4thepanamanews@gmail.com

These links are interactive — click on the boxes