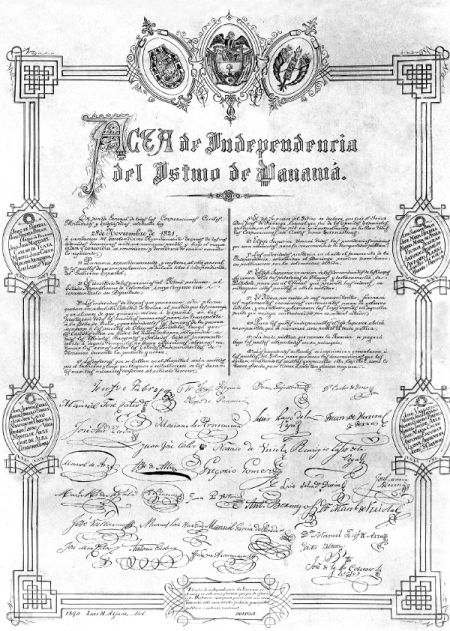

When Panama went its separate way from Spain

by Eric Jackson

The basic outlines we know, and in the mix of history and legend there are some undisputed facts. However, there is a lot still to know about the people who ended Spanish rule and threw Panama’s lot in with Bolívar’s Gran Colombia project on November 28, 1821. Perhaps in the archives of the Catholic Church, this or that Masonic lodge, some old private letters and Spanish military records we might get extra light.

The basic thing about Panamanians, though, is that with rare exceptions we are not very warlike and in 1821 there were strong antiwar sentiments behind the action that was taken.

The Spanish crown, which by treaty ruled most of the Americas as a collaborative project with the Catholic Church, had seen its arrangements broken by a Napoleonic interregnum in Spain. The French strongman’s alcoholic brother had been put in charge of Spain, Latin Americans had gone to Europe in those years and absorbed a heady mix of The Englightmente and some key activists from various parts of the vast region had cultivated Masonic connections. After some fits and starts, anti-monarchist free thinkers like Simón Bolivar were leading intredid armies against church and state. Except, in many situations they just left the Catholic Church alone. The hierarchy tended to maintain the doctrine that freemasonry was heresy, but down through the ranks of the clergy there was also the opinion that there were far worse sins than that. For example, all-out warfare between members of Catholic societies, over ties with a remote and discredited successor to the old order on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean.

The Spanish loyalists had kicked Bolívar’s ass in Venezuela — again — but instead of dying or fleeing the war zone he retreated into the wilderness, took Bogota by surprise and proceeded to conquer the old Spanish Viceroyalty of New Granada. The viceroy, Juan de la Cruz Mourgeón, fled to Panama. In a hasty and temporary reorganizaion he was demoted to governor of Panama and told to prepare for the Spanish counter-offensive.

Ecuador declared independence and joined forces with Bolívar, and the governor prepared to set out for Ecuador to rally the royalist forces. During those weeks of his preparations people in the Interior, including Spanish soldiers stationed there, rebelled at the cost and horror that such a war would entail for Panama. Were there some people more afraid that Bolívar might have to use military force to bring Panama into his political project? Were there some people who were more afraid of Panama being turned into a Spanish military bastion for a long war with dubious prospects of success? Surely there was a mix of things. Panamanians did not want war.

Governor de la Cruz Mourgeón took off, and left his lieutenant governor, José de Fábrega, in charge. How important was it for the governor to prove that he was not a wimp, after the humiliation in Bogota? Or was he just a loyal Spanish public servant who followed orders from above, no matter how daft?

In any case, Fábrega made the political rounds, in particular taking up the situation with the city council on November 20. Surely Catholic leaders were consulted as well. A town meeting — cabildo abierto — was called for November 28. Sometimes diplomat, sometimes teacher Manuel José Hurtado was put in charge of drafting a declaration. At that meeting business leaders joined with the highest ranking church and state authorities and proclaimed an Act of Independence with 12 points. The most important parts, other than saying goodbye to the Spanish Empire, were adhesion to Bolívar’s Gran Colombia and generous measures to keep the peace, allowing Spanish solders who did not want to stay on the isthmus a peaceful escape by sea to Cuba. Along with Fábrega the bishop of Panama, José Hijinio, was among the signers.

The marriage with Colombia was an unhappy one, with Panama breaking away in 1903. But we still celebrate this day.

~ ~ ~

These announcements are interactive. Click on them for more information.