You never considered that people who come into your gated neighborhood to clean houses or cut grass grew up in, or presently live in, housing like this? Or maybe you did, but you figure that the way to help out is not to pay better wages but to teach their kids English? Actually, over the past 25 years many a child and quite a few adults have used The Panama News to learn English. But if you are a newcomer who doesn’t speak Spanish, you really do need to learn some if you want to live here. It’s the polite and economical thing to do, and it may end up saving your life. Archive photo of how some of the editor’s neighbors are housed.

‘To serve the expat community you must be in English only’ and so on

an explanatory note on the 25th birthday of The Panama News

Once upon a time — for 75 years, de jura, and de facto for a generation after that — the Republic of Panama was bisected by an English-speaking jurisdiction. If the cops arrested you for walking in the neighborhood while Panamanian, you had a right to an interpreter when you went before a Canal Zone judge, but by the language of the proceedings and your very presence you would have been reminded that this was not your place. People sued, and lobbied, and protested, and fought, and died, over several generations to change this. True, Panama has a relatively young population, most of which has no personal living memory of what came before the 1977 Panama Canal Treaties. But what was has shaped what is. This is a single sovereign country whose national language is Spanish. You don’t move here and change that. If you move here you adjust to that.

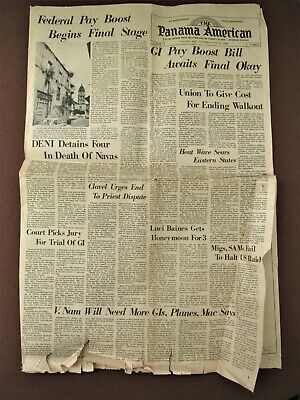

But let’s not start history with the Hay – Bunau-Varilla Treaty. There has been an English-speaking community here — mostly West Indian, largely American, partly British — since the middle of the 19th century. There are an awful lot of dual citizens here, on some interesting places on a spectrum of assimilation. And there has been an English-language press all along. In fact, two of our Spanish-language corporate mainstream newspapers, La Estrella and El Panamá América, started out as English-language publications.

La Estrella is one of Latin America’s oldest newspapers, but it didn’t start out in Spanish.

The first issue of The Star promised “relief from the monotony of our situation.” To be a stranger in a strange land who does not speak the language CAN be awfully boring, and it’s quite often expensive to have guides, interpreters or surrogates to do daily errands and to explain this place to you.

Learn the language. Learn the culture. Learn the history.

Unless you start on this as a little kid, you are likely to learn imperfectly. Better than nothing, and come to think about it, did you get a perfect education in you own native tongue?

But don’t forget who or what you are, either. It’s unlikely that you can convincingly hide it, anyway. Celebrate it and show people who are unfamiliar with it the best of it. But learn the ways and the expressions of the locals. You may need that knowledge to save your life. An uncomprehended warning can have you going into a maelstrom of some sort. The inability to call emergency services and immediately say what the problem is and where can be a life threatening handicap to you or someone you love.

So if our primarily English publication gets used by some to learn English, let some of you use the Spanish things we publish to learn Spanish.

There have been and are publications that publish each article in each language. For a micro-enterprise that’s a huge extra workload. Look at the papers that do that and their burden is usually eased by either lots of money to hire people to do the intellectual grunt work of translation, the simplicity of having to translate much less information, or usually both. The bilingual media who publish some stuff in one language and some stuff in the other without translating everything are usually the ones that explain and debate things in more depth.

The Panama American, precursor to El Panamá América.

There came a time a few years back when English education became all the rage here. The supposition was that if all of the richest and most powerful people in Panama were sent away to the United States to get university educations, then ordinary Panamanians who could do that would have an opportunity to become rich and powerful too. It’s a false expectation sown by cynical people in a tightly stratified society, people with no intention of sharing their wealth or power.

Still, if you can speak more than one language, you have more opportunities for cultural enrichment and economic advancement.

Two proposals were brought forth, neither coming from the English-speaking community. One was to make English an official second language. The other was to require English in the schools. Some were shocked that the editor of an English-language publication would do so, but I opposed both of these.

English as the official language, so that slick hustlers can get people to sign things with fine print they don’t understand, and by law judges working in a legal system that has no maxims of equity would enforce those scams? And people who were so cheated would blame the gringos? The American community does not need that aggravation of historical grievances.

Passing an English test as a requirement to get a university education? What waste of human resources when otherwise worthy and talented young people have their formal educations cut off by this. And how grossly unfair that a young woman from the comarca, perfectly trilingual in Spanish, Ngabere and Buglere, can’t get into the University of Panama for lack of English.

Do we want to tell two truths of Panama’s national development that some people who consider themselves well set don’t care to hear?

- If we are to improve the lot of the poorest of Panama’s poor, then we need more kindergarten and early elementary school teachers who know the indigenous languages that are the only tongues that many kids coming into the schools know.

- If we are to continue to be The Crossroads of the World, we should take notice that the economic hegemony of the English-speaking world has been frittered away. We need to educate some of our kids to do business in Mandarin or Cantonese, in Brazilian Portuguese or Arabic, in Japanese or Korean or French or Russian. Or so on.

The rule should not be that everyone should study English, but that everyone should study at least two languages, one of which must be Spanish. English is going to win the contest for most popular second language in the immediate future, but for Panama’s future we should diversify.

Learn your second language to the point that some of the odd machine translations will make you laugh. Learn it so that you know that good translation is not just a transliteration of words, but an explanation of one culture, or legal or political system, in terms that one who only knows the other one can comprehend. (Is the “Procurador General” the procurator general, the prosecutor general or the attorney general? How does the political epithet “gatopardista” translate into English? When is racism being spoken in Panamanian Spanish?)

Learn all this because it may save you a lot of time and aggravation, or even your life. Learn it because it’s fun, and especially if you are getting on in years continued learning is the brain exercise you need to go along with a bit of physical exercise if you are to remain in good health.

¿Música típica? Google Translate hardly begins to explain the concept. Archive photo from a years-ago National Handicrafts Fair.

Contact us by email at fund4thepanamanews@gmail.com

These links are interactive — click on the boxes