Anthropologist Fernando Santos-Granero has pieced together the story of a change agent whose life spanned an important period in South American history in his book, Slavery and Utopia, now available in English and Spanish.

Peruvian Amazonian shaman rose to power on promises of liberation and immortality

by STRI

In Peru they called him Tasorentsi: ‘divine messenger and world transformer.’ During the first half of the twentieth century José Carlos Amaringo Chico rose to power as a charismatic Ashaninka shaman-chief. His personal evolution mirrored the tumultuous times. His unwavering belief in the potential to transform the world and achieve immortality contributed to his success as a leader. Fernando Santos-Granero, anthropologist at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, tells Tasorentsi’s story in Slavery and Utopia: The Wars and Dreams of an Amazonian World Transformer, now available in both Spanish and English editions.

Tasorentsi lived for 83 years (1875-1958). To understand his life, it is useful to understand the evolution of the rubber industry. Made from latex extracted from Hevea brasiliensis and Castilla elastica trees, rubber was invented by Amerindians. But it was not in great demand until 1839 when Charles Goodyear invented vulcanization, a process that made rubber harder and more durable. When the bicycle became a popular form of transportation in the late 1800’s rubber was needed for tires, but it was expensive because it was still harvested from wild trees by indigenous and mestizo workers. The workers were often paid in advance by rubber companies to travel to areas where latex was being harvested and thus became permanently indebted.

By the late 1800’s people realized that it was easier to grow rubber trees in plantations and exploit inexpensive labor—especially in British and Dutch colonies in Southeast Asia. As new banks sprang up in China to finance the Asian plantations, the supply of cheap rubber soon far exceeded demand and the wild rubber economy collapsed in 1910.

As an adolescent, Amaringo worked as an indentured, quasi-slave laborer for a local rubber extractor and, thus, knew well the sufferings of indigenous people forced to extract rubber. After escaping from his master, he became a shaman and engaged, first as a middleman and later as a slaver, in the capture and trafficking of children and young women on behalf of white-mestizo rubber extractors. By the time the wild rubber economy collapsed, Amaringo was to experience a moral conversion, which changed the course of his life.

The Ashaninka believed they had once been as immortal as the gods but had been cast out because they did not uphold a moral code. As the rubber economy evolved and then collapsed, Amaringo took a strong anti-slavery stance and rose as the leader of several major social liberation movements, fueling his efforts with the idea that if a morally just culture could be reestablished, immortality would follow. When Seventh Day Adventist missionaries arrived, telling a similar messianic tale, he skillfully blended the two ideologies to achieve a peaceful transition.

According to the publisher of the 2018 English edition, the University of Texas Press, “Slavery and Utopia convincingly refutes those who claim that the Ashaninka proclivity to messianism is an anthropological invention.” The Spanish edition was featured virtually on the Instituto de Estudios Peruanos’ Facebook page on Sept. 3 as part of Lima’s annual Book Fair. In a YouTube interview in Spanish by Javier Torres on his channel, La Mula, Torres describes the book as a “collective collaboration.”

“Learning about the life of someone who lived in a remote area at the turn of the twentieth century and who left few tracks in the oral tradition and fewer in the written record, was a challenge,” said Fernando Santos-Granero. “I have to thank a large group of anthropologists, historians and linguists who shared their data in ways that are not necessarily customary in our profession.”

One of the central clues to the impact that Tasorentsi played as a multicultural mediator was a song from the early 20th Century, La Cancion del Rio Celeste, which Santos-Granero found in an interview of Carlos Perez Schuman recorded by anthropologist Jeremy Narby from the 1980’s. With words in Ashaninka, Yine and Shipibo, the lyrics describe a time when indigenous groups will regain their immortality and people of the Earth will once again become part of the celestial matrix.

“The song mirrors Tasorentsi’s moral conversion from a person who actively supported slavery to a person who rejected violence as the road to indigenous liberation and advocated a strategy to attain autonomy through economic independence, rejecting slavery and providing formal education to children,” Santos-Granero said.

Santos-Granero’s work at the Smithsoninan ranges from the historical study of native Amazonian peoples in colonial times to the analysis of present-day indigenous cultural practices, through the examination of the historical processes leading to the configuration of modern Amazonian regional economies. He also authored: The Power of Love: The Moral Use of Knowledge among the Amuesha of Central Peru (1991) and Vital Enemies: Slavery, Predation, and the Amerindian Political Economy of Life (2009). He is co-author of: Selva Central: History, Economy and Land Use in Peruvian Amazonia (1998) and Tamed Frontiers: Economy, Society, and Civil Rights in Upper Amazonia (2000) (both with Federica Barclay). He edited the following volumes: Comparative Arawakan Histories: Rethinking Language Family and Culture Area in Amazonia (2001) (with Jonathan D. Hill); The Occult Life of Things: Native Amazonian Theories of Materiality and Personhood (2012); Images of Public Wealth or the Anatomy of Well Being in Indigenous America (2015); and the six volumes of the Guía etnográfica de la Alta Amazonía (1994-2007) (with Federica Barclay).

References:

Santos Granero, Fernando. 2018. Slavery and Utopia: The Wars and Dreams of an Amazonian World Transformer. Tucson: University of Texas Press.

Santos Granero, Fernando. 2020. Esclavitud y utopía: las guerras y sueños de un transformador del mundo asháninca. Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos/ Centro Amazónico de Antropología y Aplicación Práctica/Instituto Smithsonian de Investigaciones Tropicales.

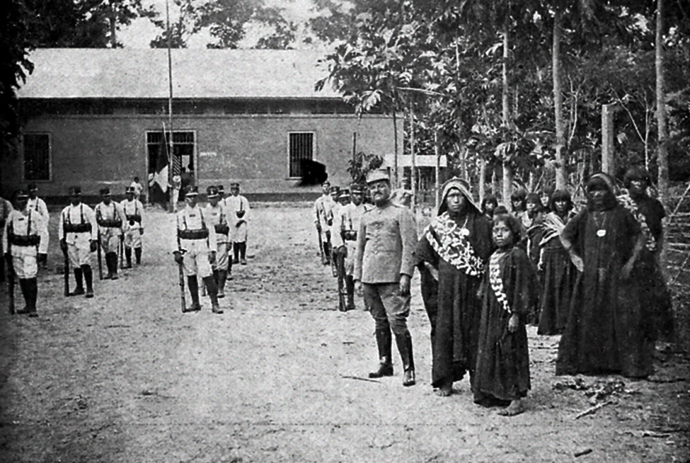

Captain Herrera and his troops, Perené Colony, June 1914. Captain Herrera (center), commander of the Mounted Infantry of the Andean town of La Oroya, was one of the first officers to be sent to the Selva Central to punish the Ashaninka rebels. Here he appears in the company of friendly Yanesha and Ashaninka chiefs while his soldiers raise the Peruvian flag. Source: Variedades No. 309, January 31, 1914. Courtesy of the Biblioteca Nacional del Perú.

Ashaninka delegation in Metraro, Upper Perené, Circa 1928. Stahl’s presence in the region created great expectations among the Ashaninka and other Selva Central indigenous peoples. The rumor was that a “white god” had appeared in the Perené Valley. As a result, people began to flock to Metraro, sometimes in small family groups or, as in this case, in larger groups led by their chiefs. Source: Ferdinand A. Stahl Photograph Collection (P08619). Courtesy of National Museum of the American Indian.

Ashkaninka people attending Sabbath School, circa 1928. This picture was probably taken in Cheni, on the Tambo River during missionaries Stahl and Peugh’s 1928 trip to Iquitos. The visitors stayed several days in Cheni teaching the “word of God” to the locals. They were surprised by the large number of people that attended the Sabbath School and their willingness to learn. Source: Center for Adventist Research (P 003995) Courtesy of Center for Adventist Research.

Stahl and 2nd Lt. Carlos Gensollen visitin the Tambo River, 1928. This picture of Stahl and 2nd Lt. Gensollen, commissioned to determine the veracity of the accusations raised by local patrones against Adventists missionaries, was probably taken in Colonia Pira. It also seems to feature chiefs Ompikiri (first man standing from left) and Tasorentsi (fifth man standing from left). Source: Stahl 1929: 19.

STRI staff anthropologist Fernando Santos-Granero.

Contact us by email at fund4thepanamanews@gmail.com

To fend off hackers, organized trolls and other online vandalism, our website comments feature is switched off. Instead, come to our Facebook page to join in the discussion.

These links are interactive — click on the boxes