Panamanian prosecutors give files about their investigation of the tax privatization scheme to the Supreme Court and the Attorney General forwards files from the Italian courts to the magistrates

Four now, or is it five?

by Eric Jackson

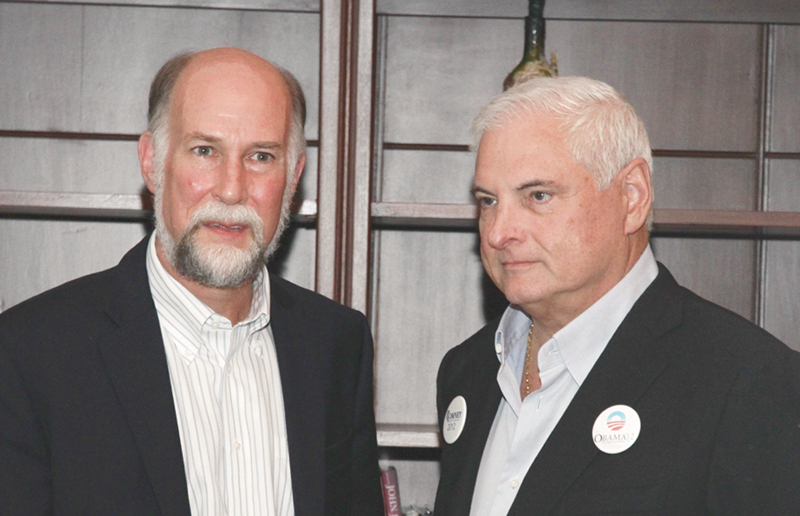

Ricardo Martinelli is sending out increasingly strident Twitter tweets from his Miami refuge, to a decreasing band of followers. Due to internal Cambio Democratico elections, he briefly had immunity from prosecution as party leader but the Electoral Tribunal has stripped that away. The cases already accepted by the high court for investigation are on hold for a moment as the magistrates consider a constitutional challenge to a law that Martinelli had passed to shorten the time to investigate criminal activity by politicians. If that law is upheld, look for some quick summary trials and Martinelli complaints about rushed justice. If it is overturned look for complex investigations of extensive criminal enterprises, leading to longer trials on charges with many counts.

The latest file sent by Panamanian investigators to the Supreme Court was sent to the magistrates by Fourth Anti-Corruption Prosecutor Ruth Morcillo. It’s about corruption in the Cobranzas del Istmo tax collection privatization scheme, for which former national revenue director Luis Cucalón is in jail and businessman Cristóbal Salerno is under house arrest. Salerno testified that he had delivered suitcases full of between $400,000 and $600,000 in cash to Ricardo Martinelli every two or three months, and that he had given Martinelli a check for $900,000 made out in the name of a company linked to the ex-president. Morcillo still has jurisdiction over Cucalón, Salerno and several other suspects but as a member of the Central American Parliament Martinelli can only be investigated and possibly tried and sentenced by the Supreme Court.

Arriving at the Supreme Court a few days earlier were case files from Italy in which former political operative Valter Lavitola was convicted for extortion and kickback schemes involving Martinelli. It will be some time before the magistrates even consider whether to open a formal investigation, as the files are in Italian and must be translated to Spanish. Revelations of documents in those files from years ago indicated schemes for Martinelli or his party’s campaign slush funds to receive money from Italian contractors, and of a partially successful shakedown of Italian construction company Impregilo. However, as Martinelli was not a defendant in those cases some material about his real or alleged conduct may not have made it into the trial courts’ files. So do we count that as a Martinelli investigation?

Cases already accepted and under formal investigation — but stalled by the constitutional motion — are about kickbacks in the purchase of food for school lunch programs and illegal electronic espionage. Particularly in the latter case, investigations are proceeding against other defendants and turning up information that will probably figure in the Supreme Court cases against Martinelli.

A third case that will be formally opened shortly has to do with hundreds of unconstitutional pardons issued by Martinelli. Under Panama’s constitution, sentences may be commuted for just about any crime for which there has been a conviction and sentence, but pardons are only allowed for “political crimes.” It might be interesting to hear Martinelli’s arguments that police killing innocent young fishermen and and then planting a firearm in their boat to plead self-defense is a political crime. Many of the pardons, however, were for public officials who stole public funds for use in the Cambio Democratico campaign. Between President Varela’s decrees and Supreme Court decisions, some 355 of Martinelli’s pardons have been revoked.