Dry times

by Eric Jackson

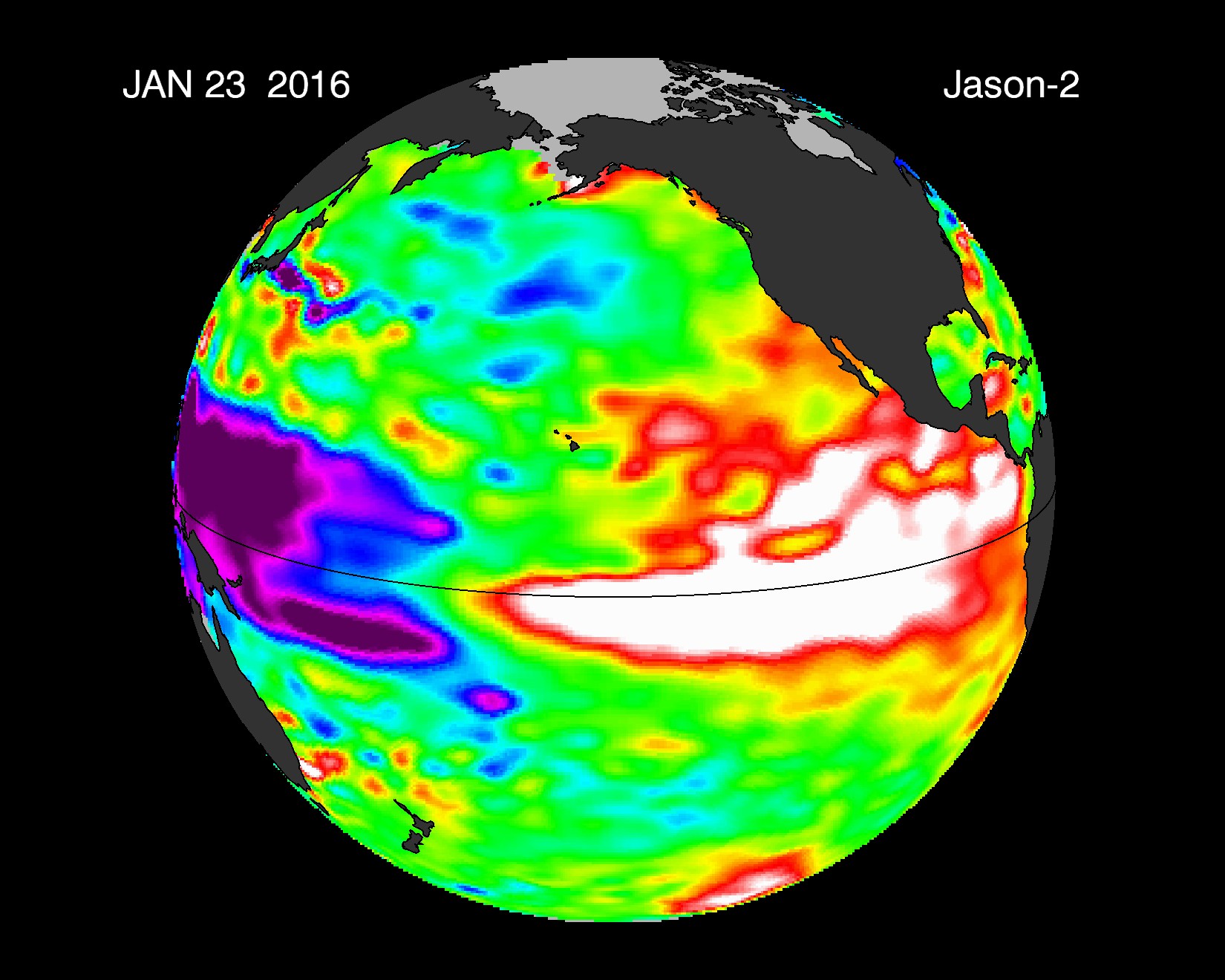

Carnival, traditionally a time of heavy water usage, approaches with much of Panama in the grip of a profound water crisis. There is an El Niño effect ongoing worldwide — they measure such things by the water temperature in the middle of the Pacific Ocean — and the hotter planetary temperatures can have widely varying effects in the local climates of different places. In most of Panama it’s a drought.

In the Panama metro area, San Miguelilto’s mayor, Gerald Cumberbatch — an Evangelical reverend who can be reasonably suspected of not much liking drunken Carnival revelry for starters — has proposed a ban on culecos. It’s a mere suggestion but it’s causing a firestorm of debate.

In Colon province’s Nueva Providencia — close enough to Gatun Lake to draw water from there, except that the Panama Canal Authority jealously guards the liquid that’s essential for the canal’s operation — neighbors without water have taken their protest to the Transisitmica. They have elicited a call for patience from the Varela administration, which says that it’s in the process of tripling the capacity of the Sabanitas plant from which the community gets its potable water.

On the Azuero Peninsula, the dryest part of Panama in ordinary times, cattle are dying and people are moving out. Some 70 percent of the wells have gone dry, and a Ministry of Agricultural Development program to drill new, deeper wells is finding no water in nearly one-third of the holes it drills. The town of Las Tablas in the heart of the Azuereo is the traditional center of Carnival festivities, which use a lot of water for the cistern cars in the culecos that spray water on daytime revelers. Talk of canceling Carnival, or at least banning culecos, is a political nonstarter because of the party’s economic importance to Panamanian tourism, both national and international. (If you care to take a conspiratorial view of things, you might start by noting that Carnival is also of great importance to President Varela’s family business, which distills the Ron Abuelo and Seco Herrerano that are consumed in mass quantities over the five-day celebration.) Panamanians are neither so carefree nor party spirited that culecos in the middle of an area that’s dying of thirst goes without critical comment, and the government has responded by stepping up its rural well drilling in the region and by restricting water usage for the culecos and barring the cistern cars from drawing water for several of the very low rivers from which towns drink.

In Chiriqui existing water problems created by human activity — hydroelectric dams that in the scheme of Panama’s energy needs make little sense but as businesses get international carbon bond revenue and seek to cash in on real estate development around artificial lakes — are aggravated by the drought. In that province authorities have called for restraint in water usage but have left the Chiriqui, Escarrea y San Felix rivers open to the cistern cars for the culecos without specific restrictions.

Panama Oeste’s population centers of Arraijan and La Chorrera have water problems that are more often created by crumbling infrastructures that are inadequate to handle the ongoing urban sprawl than they are by supply shortages. Crossing over the ridge under Cerro Campana one gets to the eastern end of Panama’s Dry Arc that runs along the western littoral of the Gulf of Panama. The water shortages are more often of natural origin there. Panama Oeste’s main Carnival locale, Capira, has reduced culecos from last year’s 10 to six this time, forbidden the cistern cars’ refills over the course of a day and restricted culeco hours to between 11 a.m. and 5 p.m.

The next province over, Cocle, is severely hit. The water parade that’s the center of Carnival revelry in Penonome is still on, but the Zarati River on which it is held is very low and had to be dammed upstream from the Carnival site to make it deep enough for the city’s drinking water intake to function. Water can only be drawn for culecos in three of the province’s rivers — 14 cistern cars per day from the Zarati River in Penonome, 14 from the Chico River in Nata and 13 per day from the Rio Grande to supply festivities in El Valle, Rio Hato and Anton. Most of the province’s creeks have been dry since December and now many of the larger rivers are dry or down to a trickle. Several of the province’s rural aqueducts, both those that take surface water and those fed by wells, are in serious crisis. It’s likely to affect Carnival tourism as people in the city may decide not to escape to their cottages in the Interior at which there is no water. The problem with a number of the rural aqueducts is that these are jury-rigged contraptions that have not been expanded to deal with growing populations that depend on them, such that they may keep water coming to areas along their principal mains but no longer have pressure to get water out to neighborhoods at the ends of their lines. One can get into some interesting social, historical and political analyses about that, but meanwhile some people are leaving waterless areas to stay with family or friends who do have running water, while others are adjusting their lifestyles to include the hauling of water from community spigots as part of their daily routines.

~ ~ ~

The announcements below are interactive. Click on them for more information