People wait in line to receive a vaccine shot against COVID-19 in Belgrade, Serbia, Aug. 17, 2021. Serbia and other countries have started administering booster doses. Meanwhile, more than half the world’s population has not had a first dose. AP Photo/Darko Vojinovic

Are COVID-19 boosters ethical, with half the world

waiting for a first shot? A bioethicist weighs in

by Nancy S. Jecker, University of Washington

Should countries that can afford COVID-19 booster vaccines offer them to residents if scientists recommend them?

The director-general of the World Health Organization, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, has made his position clear, calling for countries to impose a moratorium on boosters until 10% of people in every country are vaccinated. His plea comes amid mounting concerns about the slow progress getting COVID-19 vaccines to people in low-income countries.

Like the WHO, some ethicists, including me, have argued that the world must stand together in solidarity to end the pandemic.

Yet as of Sept. 14, of the 5.76 billion doses of vaccine that have been administered globally, only 1.9% went to people in low-income countries.

Meanwhile, many wealthy countries have begun offering COVID-19 boosters to fully vaccinated, healthy adults.

Early evidence on the benefit of COVID-19 boosters to protect against severe disease and death cuts both ways. Some experts tout their benefits, while others argue against them for now.

As a philosopher who studies justice and global bioethics, I believe everyone needs to wrestle with another question: the ethics of whether to offer boosters while people in poor countries go without.

A dangerous gap

The WHO’s call for a moratorium on boosters is an appeal to fairness: the idea that it’s unfair for richer countries to use up more of the global vaccine supply while 58% of people in the world have not received their first shots.

In some countries, such as Tanzania, Chad and Haiti, fewer than 1% of people have received a vaccine. Meanwhile, in wealthy nations, most citizens are fully vaccinated – 79% of people in the United Arab Emirates, 76% in Spain, 65% in the U.K., and 53% in the U.S.

In the U.S., the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has recommended boosters for moderately to severely immunocompromised people. President Biden has publicly endorsed offering boosters to all Americans eight months after they complete their second shots, pending Food and Drug Administration approval. Yet on Sept. 17, the FDA’s advisory panel recommended against a third dose of the Pfizer vaccine for most Americans, though they did endorse boosters for people over age 65 or at higher risk.

On Aug. 11, before the CDC had authorized boosters for anyone – including immunocompromised people – it estimated that 1 million Americans had decided not to wait and got a third vaccine. It is unclear whether some of them were advised by doctors to seek a booster shot based on, for example, age or compromised immunity. Some healthy Americans have reportedly lied to gain access to unauthorized shots, telling pharmacists – falsely – that this is their first shot.

In addition to raising concerns about fairness, gross disparities between vaccine haves and have-nots violate an ethical principle of health equity. This principle holds that the world ought to help those who are most in need – people in low-income countries who cannot access a single dose.

There’s also a purely utilitarian case to be made for delaying boosters. Even if boosters save lives and prevent severe disease, they benefit people far less than first shots, a notion known as diminishing marginal utility.

For example, the original laboratory studies of the Pfizer vaccine showed more than 90% protection for most people against severe disease and death after the primary, two-dose series. Booster shots, even if they boost immunity, give much less protection: perhaps less than 10% protection, according to a preliminary study.

As a recent article in a leading medical journal, The Lancet, points out, “Even if boosting were eventually shown to decrease the medium-term risk of serious disease, current vaccine supplies could save more lives if used in previously unvaccinated populations than if used as boosters in vaccinated populations.”

Moreover, when scarce vaccines are used as boosters, rather than as first shots for the unvaccinated, that allows the virus to replicate and mutate, potentially creating variants of concern that undercut vaccine protection.

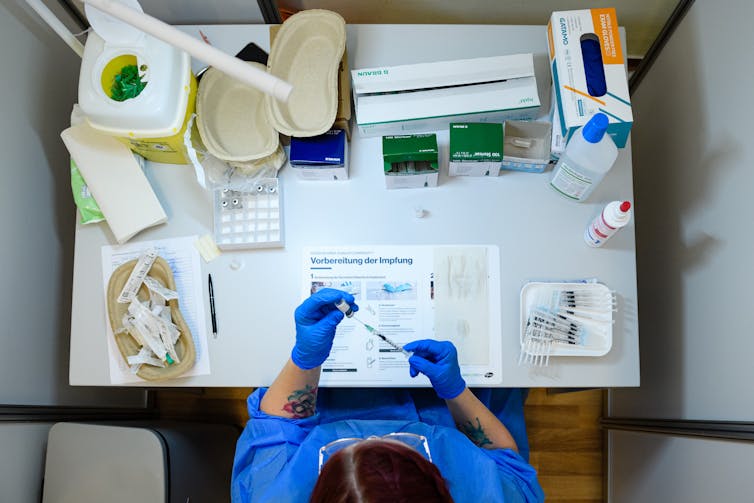

Booster vaccinations are underway across Germany for elderly patients, who were among the first to receive shots in the initial vaccine rollout. Many countries have started administering boosters, though half the world is still waiting for a first shot. Jens Schlueter/Getty Images News via Getty Images

Booster vaccinations are underway across Germany for elderly patients, who were among the first to receive shots in the initial vaccine rollout. Many countries have started administering boosters, though half the world is still waiting for a first shot. Jens Schlueter/Getty Images News via Getty Images

Buy it, use it?

While the ethical argument for delaying boosters is strong, critics think it is not strong enough to override every nation’s duty to protect its own people. According to one interpretation of this view, countries should adopt an “influenza standard.” In other words, governments are justified in prioritizing their own residents until the risks of COVID-19 are similar to the flu season’s. At that point, governments should send vaccine supplies to countries with greater needs.

One could argue that since rich countries have bought millions of doses, they are the rightful owners of those vaccines and are ethically free to do as they wish.

Yet critics argue that vaccines are not owned by anyone, even by the pharmaceutical companies that develop them. Instead, they represent the final part of product development that is years in the making and the result of many people’s labors. Moreover, most COVID-19 vaccines were publicly funded, principally by governments using taxpayer dollars.

Since 1995, the World Trade Organization has required its member states to enforce intellectual property rights, including patents for vaccines. Currently, however, the trade organization’s members are debating proposals to temporarily waive patents on COVID-19-related products during the pandemic.

Some commentators suggest that the whole debate over boosters is overblown and not really about ethics at all. They propose simply calling boosters something else: “final doses.”

But regardless of what we call boosters, the ethical question the WHO’s director-general raised remains: Is giving these shots a fair and equitable way to distribute a lifesaving vaccine?![]()

Nancy S. Jecker, Professor of Bioethics and Humanities, School of Medicine, University of Washington

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.