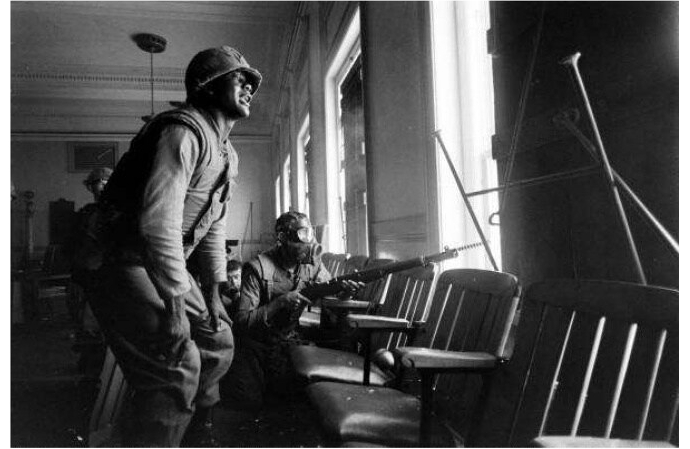

Back in january 0f 1964: A US Army sniper and spotter in the Sojourners Lodge Masonic Temple in Cristobal, back then in the Canal Zone on one side of Bolivar Avenue while the other side of the street was the city of Colon, under the jurisdiction of the Republic of Panama. These days there is no international border running down the middle of the street — that’s something for which Panama’s martyrs died. The fighting around the Masonic Temple and the YMCA next door to it was furious and controversial. There were people killed on both sides. The usual version omits events outside of Panama City and adjacent parts of the Canal Zone, but in fact there were several days of a national uprising against the existence of the US enclave, with disturbances, demonstrations and strikes across much of Panama.

A Panagringo history major from Colon remembers

by Eric Jackson

First of all, how to identify the characters?

Me? Just 11 years old then, living by the old Coco Solo Hospital out on the Trans-Isthmian Highway, a weird kid, kind of a social outcast. Born in a US hospital in a part of Colon occupied by the Canal Zone, which was later turned over to the Republic of Panama. Born to American parents.

Under current laws, that makes me a dual US and Panamanian citizen by birthright. (There are xenophobes in the legislature who propose to strip those of us born in Panama to non-Panamanian parents of our citizenship. Can you say “fascist guttersnipes?”)

I went to Canal Zone schools until age 13, then moved to Michigan. With the exception of some non-immersive Spanish classes, my entire formal education was in English.

So does that make me a Zonian? Or, as this gringo chulo on one of the Zonian Facebook groups insisted, am I out of the club on account of my religion and creed — perceiving no halo around Donald Trump, thinking that QAnon and his devotees don’t so much need to have their heads examined as they need to be put on trial for fraud and incitement of violence, being a democratic socialist all of my adult life and an active Democrat, being anti-racists, choosing to live in post-colonial Panama? I Yam What I Yam, and moreover part of my strange economy and lifestyle is that I’m a subsistence spinach farmer, so have prepared to go the distance with Bluto.

The Zonians? The white minority of the civilian population of the segregated Canal Zone. There were about half as many of them as the two-thirds of the Panama Canal Company work force who weren’t American — most of these black people who traced roots through the West Indies. Back then the white Zonians were in toto paid more than the black majority. It was remarkably like the Jim Crow south, except that in both places things were changing. All white Zonians were not belligerent rednecks, but those who were would shove everyone else aside and shout everyone else down and present themselves as the only Zonian voice.

The military kids would go to school with the Zonians, as did a few Panamanian kids whose rich parents paid tuition. But a great many of the white Zonians treated the troops with scorn — “RAPs,” for Regular Army Personnel. Once there was a RAP who was stationed in the Canal Zone back in the 1920s as he honed his skills as an officer and administrator on his way up the ranks. He used to drink at Bilgray’s Tropico Bar in Colon. They called him Ike. Prudent about what he said like a soldier avoiding controversy and demerits, but observant of his surroundings. He was not the only US military officer who saw Canal Zone and Panamanian society the way that he did. The guy doesn’t much fit into current Zonian Hall of Shame – in which Jimmy Carter is the key villain — but Dwight D. Eisenhower was the guy on the US side who set into motion the eventual decolonization of Panama.

The brass, by and large, thought of the West Indians as a good pool of recruits to turn into soldiers, sailors and airmen, and intermediate to that, to work as civilian employees on the complex military bases. Through service in the ranks, one could get US citizenship. For working as a civilian for Uncle Sam, one might eventually get a visa to move to the US and get a green card, later perhaps citizenship. People took advantage of these opportunities and sponsored family members to move to the States after them. They generally retain places in their hearts for Panama — the

feeling is a major part of Panama’s tourism business even if those who allegedly speak for that industry ignore them in favor of white people with a lot of money. (Or, in the case of the related but different “residential tourism” part of the real estate business, often thugs of whatever color or nationality looking to launder large sums of money.)

On the other hand the US military officer corps tended to look upon the white Zonians as these belligerent louts. It’s human nature for disdain to be met with reciprocity.

Adding to the tension was that under US law, the Canal Zone was a military dictatorship of sorts. Yes, there were courts, and with some fine and fair judges. But as it was under US jurisdiction but neither a US state nor an incorporated US territory, the constitutional doctrine set forth in the Insular Cases applied. That legal construct had it that the US Constitution didn’t necessarily apply. The Canal Zone governors were appointed by the US presidents and by custom were current or former US Army Corps of Engineers major generals. The governors enjoyed broad summary powers that kept a lot of possible controversies out of the courts. A Canal Zone resident thought troublesome could be sent back to the USA forthwith, with no more process of law than a letter from the governor ordering such deportation, and no option of just moving across the street to Panama if a US citizen.

Albeit before Pearl Harbor, part of World War II — recall that Ike had something to do with that war — was a US-engineered Panamanian coup d’etat by which Hitler’s friend Arnulfo Arias was removed as president in October of 1941. Panama’s Policia Nacional, later to become the Guardia Nacional, then the Panama Defense Forces, then after the 1989 invasion the various forces under the present Ministry of Public Security, was by and large set up by the Americans in the first place. Its commanders had subordinate liaison officers to handle relations with the Canal Zone Police and often had personal working and social ties with the US military brass on the isthmus.

One such friendship was between José A. Remón, the guardia officer most involved in the 1941 coup, which brought about a new civilian president rather than direct military rule, and several other behind-the-scenes guardia-engineered changes of government. Washington always approved. Then, shedding the background role, Remón went and got himself elected president of Panama, about the time that Ike got himself elected president of the United States. The men understood one another, the issues in the Canal Zone and the problems between the United States and Panama. The two men made the first step in a long process that would devolve the US enclave that bisected the Republic of Panama into Panamanian sovereignty. Remón was assassinated while the final touches were being put on the resulting treaty, which nevertheless bears his name along with Eisenhower’s.

Had John F. Kennedy heard about the white Zonians when he was in the US Navy during World War II? In any case Kennedy’s foreign policy was largely a continuation of Eisenhower’s, and in Panama that included an agreement with then Panamanian president Roberto F. Chiari to fly the Panamanian flag next to the US flag in all civilian sites in the Canal Zone where the American flag had flown alone. There were protests, lawsuits and resignations in the Canal Zone as soon as the policy was announced.

Then Kennedy was assassinated and Lyndon B. Johnson put a lot of foreign policy initiatives on hold for review.

One reason for the hiatus was that from the Kennedy White House the president and his brother Robert had been running covert operations that included assassinations, which has included several attempts on Fidel Castro’s life. Johnson didn’t know if Kennedy had been murdered by a Cuban cut-out in retaliation and given Cold War tensions could not mention even the suspicion, nor let the Warren Commission delve into that question in any serious way. The brief immediate aftermath of Kennedy’s death was the wrap-up of the White House’s little murder incorporated and review of a number of foreign policy decisions. It’s not to say that all CIA and military special ops hit men were stood down for the duration of the Johnson administration, but the man from Texas was, despite the later caricatures of antiwar activists, more cautious than his predecessor.

That December the Canal Zone was informed that the new flag policy would go into effect in January. White Zonians aimed protests at the governor, Robert J. Fleming. Judge Guthrie Crowe, in a decision that questioned the wisdom of the flags policy, declined to strike it down.

Solitary flagpoles were left unused in an interim measure so that new dual poles could be installed. Then in Gamboa a Canal Zone police officer, Gordon Bell, raised the American flag in front of the policy station there.

Demonstrations took place at the schools, where students and sometimes parents raised American flags.

Then came the Panamanian kids from the Instituto Nacional, to raise their flag at Balboa High. The president of the Balboa student body would have given the Panamanians a cordial greeting, but he was shunted aside and a scuffle broke out in front of the flagpole, in which the Panamanian flag was torn. It was the spark that set Panama aflame.

The action in Panama City and across the street largely came to center in front of the old Tivoli Hotel, where now stands the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute’s Tupper Center.

On the Panamanian side a gun store was looted and the arms passed out to the untrained.

On the American side the first responders were the Canal Zone police, and some armed men in civilian clothing who have never been definitively identified as either plainclothes or off-duty cops or Zonian civilians.

In any case the bloodshed had already begun before US Army General Andrew P. O’Meara sent in infantry units from Fort Clayton and ordered the Canal Zone police to leave.

US Army Brigadier General George Mabry, who had been awarded the Medal of Honor during World War II, took command at the Tivoli and after the police stopped shooting and left went out in full battle dress with about 15 soldiers who had bayonets affixed to their rifles and moved slowly forward to remove the protesters from the Canal Zone. Without Mabry or those alongside him firing a shot, the protesters moved back. However, plenty of shooting, much of it completely wild, continued.

The Americans fired at whom they thought had shot at them, including an 11-year-old girl on a nearby balcony, whom they had mistaken for a sniper.

The tales of American soldiers — or in some cases marines — opening fire on crowds with machine guns were not and are not true.

Where was the Guardia Nacional in all this? There are different accounts of why and it’s well nigh impossible to read a dead man’s mind, but in any case President Chiari ordered them off the streets and into their barracks.

The usual presumption is a reluctance for Panamanians to kill one another over a problem that the Americans started. Instead, Chiari broke diplomatic relations with the United States, leading to an impasse and then to a couple of rounds of long negotiations about the status of the Canal Zone.)

Over on the Atlantic Side, where this reporter lived, there was a delay before the protests began. January 9, 1964 was a Thursday, but the heavy violence didn’t break out in Colon until the weekend.

The first call in Colon was from the dock workers, who marched in protest.

A warehouse in Cristobal was set ablaze. The Cristobal train station was vandalized. Protesters broke into and damaged the Masonic Temple and the YMCA in Cristobal.

Infantry units from Fort Davis deployed, at first with weapons unloaded to avoid further bloodshed and provocation.

They cleared the people out of the YMCA building and Masonic Temple, and set up positions there. But the snipers, young men with no military training and pathetically small arms, came out on the Panamanian side. Three US soldiers were killed and nine wounded. This reporter’s father was working at the emergency room at the Coco Solo Hospital when the American casualties came in.

On the Panamanian side some snipers were shot, one of them, 18-year-old student Renato Lara, fatally.

Guardia Nacional Sergeant Celestino Villareta, attempting to restore some peace and order along the boundary was shot by some unknown person, and when an ambulance came to rescue him it was fired upon by US troops in the Masonic Temple.

In an attempt to flush out a suspected sniper, a US soldier fired a tear gas grenade that ended up in a Guna family’s tiny apartment. Six-month-old Maritza Alabarca was overcome by the gas and died but to this day the US government claims that since tear gas is defined as non-lethal American forces had nothing to do with the little girl’s death.

The use of the Masonic Temple and YMCA as American military redoubts, which drew damaging sniper fire and also became the targets for molotov cocktails, ended up before the US Supreme Court. The justices in Washington held that where US forces go into combat, Uncle Sam pays for no property damage.

To bring order to Colon, the Americans returned one Omar Torrijos, who had been head of the Guardia Nacional garrison there, from David where he had been transferred so has to lead the restoration of order from the Panamanian side.

Across the Interior there were instances in which US-owned or US-identified farms and businesses were attacked. Workers at the US-run banana plantations walked out on strike. The media railed against the Americans, with only a few exceptions. Masses were said. Panama’s lags were lowered to half-staff. There was huge attendance at some of the funerals.

As much as Panama’s 1821 independence from Spain and its 1903 separation from Colombia, The Day of The Martyrs marked another huge stride along the still incomplete path to Panama’s independence as a sovereign nation.

People still argue. There are historical points still to be clarified. But these are the reasons why so much of the country is closed today. We look where we have been as a nation, and Panamanians mourn on this day.

Contact us by email at fund4thepanamanews@gmail.com

To fend off hackers, organized trolls and other online vandalism, our website comments feature is switched off. Instead, come to our Facebook page to join in the discussion.

These links are interactive — click on the boxes