A bad week for the Martinellis

by Eric Jackson

The Martinelli family has had a rough week. The ex His Excellency got back into some old trouble before the high court, without a word on his behalf from the ultimate beneficiary of his crime.

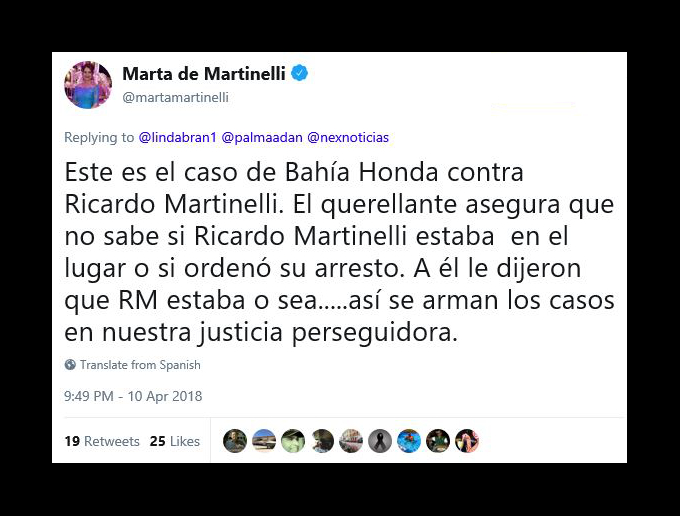

The former first lady did rise to her jailed husband’s defense, but foolishly. “This is the Bahia Honda case against Ricardo Martinelli,” she tweeted. “The complainant says that he doesn’t know if Ricardo Martinelli was in the place or if he ordered his arrest. They told him that RM was there, that is… this is how they make their cases under our persecuting justice.” As if dozens of families were not driven from the homes and lands they owned without legal process, in two waves in 2010 and 2012. As if the former governor of Veraguas blinked ever so slightly and wrote in his illegal 2010 eviction order that this was due to Martinelli’s presidential order — an annotation that got the guy fired. As if among the many residents who were driven off in the next wave of evictions there were not many who not only identified Ricardo Martinelli the scene but recounted his specific Holy Week threat that whoever did not forthwith sign his or her property over to French-Italian playboy Jean Pigozzi, heir to the Simca auto fortune, would be thrown in jail. As if the dozens of police officers and the crews that demolished people’s homes are going to take the fall for Ricardo Martinelli and testify that the ex-president had nothing to do with it, that this was an idea that just came into their heads.

Ah, but Pigozzi is a philanthropist, a good guy who hangs out with Martha Stewart and Google’s Sergey Brin and Mick Jagger and the Martinellis and Pipo Virzi and Gabriel Btesh and Riccardo Francolini (the latter three out on bail, Ricardo Martinelli in jail in Miami and his two sons fugitives from justice). For the sake of science? The Liquid Jungle Laboratory which Pigozzi established on nearby Isla Canales — which he and then-President Martinelli purported to rename Isla Simca — had been established a few years before. These dispossessions, of people who owned their properties by decades of adverse possession that gave them full ownership rights under Panamanian law, were not for the purpose of scientific research. They were so that Mr. Pigozzi would not have their houses in the view from his house. And one of those who objected, so was arrested, brought his private criminal prosecution, was blown off by prosecutors and summarily thrown out of court by judges, finally got a day in the Supreme Court, which decided on April 10 to continue the disrupted criminal proceedings against the former president. This criminal case is far from over.

(Were anyone to proceed against Pigozzi, she or he would first have to surmount a statute of limitations barrier. That case would be separate from Martinelli’s as Pigozzi is not a member of the Central American Parliament so as to give rise to the high court’s direct jurisdiction over him.)

So add that to the front-burner case of illegal eavesdropping against the former president, along with the more than a dozen other matters at various phases on the docket.

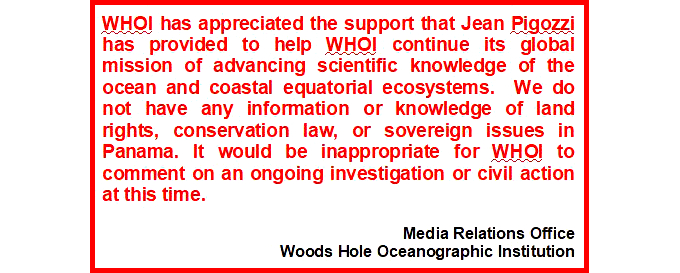

To the scientific institutions that have or had relationships with Pigozzi’s Liquid Jungle Lab, there are revealing denials or evasions. The US quasi-govermental Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute did not respond to this reporter’s question about their current relationship with the lab. In fact, they erased references to such relationship as they had from their website, but did not take into account the existence of cached copies and accounts from other sources. In 2011 and again in 2012, then STRI director Biff Bermingham and Eva Pell, the Smithsonian Institution’s undersecretary for science, toured the Liquid Jungle Lab and did a presentation about a STRI exhibit to be installed there. But less than a month after the 2012 visit the Easter Week expulsions took place, and less than a year and a half after that a crew from Washington DC came to STRI headquarters in Ancon and summarily expelled Bermingham from that organization. There has been a concerted effort since then to erase online references about him and he is the only living ex-director not to be listed as “emeritus”— or at all. Yet as fleeting and cautious as the Smithsonian’s relationship to Pigozzi’s lab might have been, at the time the STRI name was used to validate the operation.

The Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute is a private organization with a staff of about 1,000 that’s based in Massachusetts but roams the world’s oceans and seas. Its relationship with Pigozzi was and is older and closer. Colonial mentalities and the fruits thereof be damned when WHOI is dealing with celebrities. They did respond to this reporter’s query, in a way that ought to shock American educational institutions with operations abroad.

In any case acting magistrate Abel Zamorano is the acting prosecutor and magistrate Harry Díaz is the acting judge, with a nine-member panel of magistrates and alternate magistrates to sit in judgment as the jury if the matter ever gets to trial. Zamorano has three months to put his case together and either move to take it to trial or not.

Zamorano and Díaz are both Martinelli appointees, but with the ex-president’s sinking fortunes it seems that such ties are ever less of a factor. What sort of a factor existing vacancies on the court and a political stalemate over filling them may be is an even wilder card in the legal calculations.

Like father? The sons are absent and so far on the losing end

A lower court judge had ruled that the prosecutors’ time to bring a case in the Odebrech bribery and kickback scandal had run out, her ruling was upheld by the appeals court, but this week the Supreme Court overturned the appellate decision and remanded the case back down. This reopens the case against an unknown group of individuals, but two of whom are definitely known to be the former president’s sons, Ricardo Martinelli Linares and Luis Enrique Martinelli Linares. They received money from Odebrecht and laundered it through an international chain that went though Andorra and ended up in bank accounts in Switzerland, which the Swiss authorities froze.

Multiple money trails through many jurisdictions involving many people — that’s a complex investigation. However, in the middle of last year a judge of Panama City’s 12th Penal Court ruled that it was not a complex case, thus ineligible for the time extension to investigate those sorts of cases. The appeals after the judge timed the investigation out appear to have ended this past week the high court reversed and gave the prosecution an extra year to investigate their case.

The Martinelli brothers have been unavailable during all of this. While they were on their merry flight a family helicopter was seized by authorities in Mexico but the trail was probably lukewarm then and is much colder now. It would not be until sometime after the investigation is concluded, if formal charges are preferred, before an INTERPOL warrant might be requested in that matter.

It is, however, not the only penal matter for the younger Martinellis.

On April 11 the Supreme Court slapped down a series of impediments interposed by Ricardo Martinelli Linares against a criminal investigation of a gambling offense. It is alleged that during the time of his father’s presidency a scratch-off lottery game, Buko Millionario, was created and approved under someone else’s name, but that Ricardo the son was the actual beneficial owner. That hidden interest would violate Panama’s gambling laws and perhaps some of this country’s skimpy inhibitions against conflicts of interest. But after three years of constant dilatory tactics, the magistrates told the prosecutors that they may continue with their investigation of the case. The court did, however, limit prosecution demands for banking records. It was a 5-4 decision of a full court panel, with alternates and unreplaced magistrates holding over from expired terms participating.