Country dogs

by Eric Jackson, some photos by José F. Ponce

No evidence from Panama suggests intensive raising of dogs for meat. These dogs were probably used for hunting and guarding settlements. As in most tropical dog populations, mortality was high and dogs’ lives were short, usually 3-5 years.

Katherine M. Moore

Department of Anthropology, University of Pennsylvania

about the Sitio Conte tombs that date between 450 and 900 AD

Can we for once ditch the Eurocentric version of our history? The story of Panama’s dogs certainly didn’t begin when local people discovered strange visitors from across the ocean on the Caribbean beaches of the isthmus. But just as our geologic history is complicated and obscure enough to get some of the world’s most learned scientists arguing among themselves — and the very best of them admitting to important unknowns — information about the very earliest people and dogs in Panama is shrouded in the mists of time.

More properly, the cover is not mist but the Pacific Ocean and the Caribbean Sea. What we know about the timeline of human settlement of South America and the genes and cultures of the oldest humans who have left traces to be discovered on that land mass leads us to infer that some of the people who had crossed an Arctic land bridge from Eurasia when an ice age had lowered sea levels relatively quickly made their way from North America to South America. If we presume that the early migration routes mostly went the way of least resistance along the beaches, those routes were long ago inundated by rising sea levels. There are claims of much older human habitation sites in Brazil and Uruguay, but the Monte Verde site in the mountains Chile dates back 14,600 years. There, some nearly 9,000-year-old bones that were recovered and tested yielded some mitochondrial DNA that establishes a relationship along the maternal line with people who crossed the Bering Strait about 17,000 years ago. There are claims — not universally accepted — that an archaeological site in the Azuero Peninsula may date back more than 11,000 years. It is well documented by fossilized pollen and starch grain analysis by Dr. Dolores Piperno of Princeton University and the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute that corn (maize) was being cultivated here some 7,800 years ago. So far, however, there have been no human or dog remains encountered in Panama from the times in which the trek from the Arctic to the Chilean Andes must have taken place. The general belief among the experts is that much or all of the migration route through Panama is now underwater.

(Do we want to throw theoretical curveballs into the mix and talk about ancient maritime migrations, including perhaps from Indonesia, Polynesia and Australia, that brought people and dogs to South America? There are also tales, with even less evidence, of pre-Columbian visits from Asia and even Africa. Would DNA analysis of dogs confirm or rule out such things? Perhaps, but these days grant money for such research would be hard to come by. This writer’s hunch is that humanity has explored, traded and diffused its cultures and DNA far and wide in antiquity, and time and again broken off its long-distance ties for all sorts of reasons. In historical times we know of the failure of Norse colonization in North America, the serial destructions of the Library of Alexandria and a change of dynasties resulting in the suppression of a Chinese age of exploration and the knowledge that it has developed. Shouldn’t more recent experiences of the suppression of certain lines of human inquiry, cultures and knowledge — ranging from the Nazis to the Khmer Rouge and including today’s Christian and Muslim fanatics — warn us of knowledge suppressed over the long sweep of ancient times? Technologies may have changed, but ancient scriptures suggest that human nature has not changed nearly as much.)

In any case, our knowledge of Panama’s pre-Columbian dogs is of old but far more recent vintage, and perhaps by inferences of things that we can observe today. There are a few noteworthy archaeological sites, the written observations of some of the earliest Europeans here and inferences that can be drawn about cultural diffusion routes from discoveries in paleobotany.

Botany? We know, for example, that a number of important food plants were derived from the nightshade family in the Andes — peppers, eggplants, tomatoes and potatoes, to name a few — and had spread from there through much of the Americas long before the European conquest. Starch grain analysis has shown how in a period of about 1,000 years a variety of hot pepper arose in Bolivia, spread to much of South and Central America, and made its way into the Caribbean islands as far north as the Bahamas. From similar research we now know that corn was first domesticated in a valley in Mexico and was a spectacular success of agricultural diffusion throughout most of the Americas.

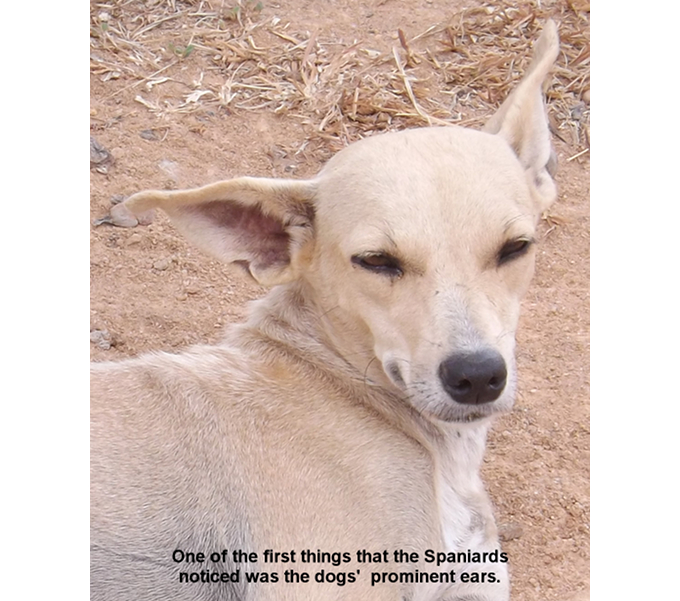

And dogs? If the generally held theory is that domesticated dogs derive from the wolves of North America and Northern Eurasia, several sorts of Latin American dogs have large upright ears that look a lot more like those of African jackals or Australian dingoes than those of wolves. Is that just a body morphology trait that tropical dogs of different lineages have developed because it’s a convenient way of dealing with the heat, or are a certain type of Panamanian dogs commonly found in our countryside related to Latin American breeds that also have big upright ears, dogs like the Peruvian Hairless or Mexican Chihuahua?

Spaniards who came to the isthmus noted that they encountered hairless dogs, one of the first things that the local people — Cuevas, speakers of a language of the Chibchan family that had its remote origins on the Colombian plateau around Bogota — did was to tell the Spaniards the general direction of golden Peru, then ruled by the Incas. Archaeology gives us art with depictions of the Peruvian Hairless breed that are pre-Incan.

For many historical reasons from colonial and post-colonial times, Panama may be the narrowest part of the Meso-American isthmus but it’s more of a South American country than a Central American one. All our our seven indigenous nations are of one or the other of two linguistic families — the Chibchan and the Chocoan — which migrated here out of South America. In Spanish colonial times we were part of the Viceroyalty of New Granada, along with modern-day Colombia, Venezuela and Ecuador. We are one of the Bolivarian republics, the countries of South America liberated from Spanish rule by a movement led by the Venezuelan Simón Bolívar. We only definitively separated from Colombia in 1903. We were never part of the Aztec or Mayan cultural worlds or their precursors, we were part of neither the colonial Captaincy General of Guatemala nor its ephemeral post-independence successor the United Provinces of Central America. The notion of Panama being Central American is recent, more than anything a product of the admiration that much of our tiny inbred aristocracy has for the powers and privileges of Central American banana republic autocrats and their social circles.

And yet, in the course of his digs around Panama’s Parita Bay that date between 2200 BC and 700 AD, Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute archaeologist Richard Cooke found the remains of a cardinal. In recorded times, and presumably back then, the cardinal’s range does not extend south of Mexico. By the time that the Spaniards arrived on the scene more than 800 years later, they found the local people fond of keeping birds in cages. So was the cardinal evidence of a trade relationship, direct or indirect, with one or more of the ancient civilizations of Mexico? And if such a trade route did exist, did dogs as well as birds move along it?

Cooke, like archaeologists from Harvard and the University of Pennsylvania, has worked on digs attributed to the Coclean culture that was divided into various warring regions when the Spaniards arrived and whose only intact cultural remnant is the Bugle, the Buglere-speaking people now in enclaves in the mountains of northwest Veraguas province and along the Caribbean littoral in Veraguas and Bocas del Toro provinces. In very recent times most of the Bugle have converted to an Evangelical strain of Christianity but the evangelization did not erase their culture nor obliterate memories of what it was before the missionaries arrived.

The Bugle do keep dogs. Do they care to talk to anthropologists or dog enthusiasts about it, or to allow a census and analysis of their dogs? Would that which could be learned from such inquiries inform us about Panama’s country dogs in general, or how long some of their common traits have been characteristic of the canine population on the isthmus? Perhaps.

Probably some new investigations of old archaeological evidence would shed more light on the matter.

In the 1930s Harvard and 1940s Sitio Conte digs as well as later work in central Panama by Dr. Cooke, we found that over many centuries the Coclean culture used dog teeth for necklaces and other ornamentation. One apron made of dog tooth beads found as grave goods in the tomb of an apparently elite woman at Sitio Conte had the teeth of perhaps 70 dogs in it. So were the dogs ritually sacrificed or less ceremoniously killed, or did people of that culture just extract and save the teeth when one of their dogs died? And if the dogs were killed, were they eaten? Most of the few archaeologists who have published things about the Coclean culture’s dogs think not, largely on the strength of no butcher marks found on dog bones that were unearthed. But Panamanian archaeologist Carlos Fitzgerald, based on the places and strata where dog bones were found, thinks that they probably were eaten. At the time of the Spanish conquest, however, the conquistadores didn’t mention dog meat as part of the indigenous diet. In fact they noted that for common people the diet didn’t include meat of any sort.

So what did the dogs in this predominantly agricultural pre-Columbian society eat? From an analysis of their teeth, apparently a lot of soft food, apparently including a lot of corn. That would not be far from what campesinos of modest means feed their dogs today — scraps of whatever they eat, which is a mostly starchy diet.

Coclean art, which comes down to us mainly as painted ceramics and small gold pendants, was fairly abstract. While a few pieces undoubtedly depicted dogs, how accurately so can be questioned.

But why look to any of that when there was a rich find of some 228 dogs buried at Sitio Conte? The University of Pennsylvania’s Katherine M. Moore notes that from analyzing their teeth it can be determined that they were all of one breed. She would like to see further research on Coclean dog remains, which she thinks would give us a better idea of what they ate, from whence the breed came and “unique information on local husbandry and test models for the entry of dogs into South America.” Or might we find that the Coclean dogs came here from South America? And might it just turn out that the hardly little dogs with the big ears, described by Spay Panama founder as “these little reindeer,” are actually representatives of a very old Panamanian breed?

They might be “de raza” (pure bred) instead of “criollos” (mutts)? That could be interesting, but because of certain aspects of Panama’s culture and history even solid proof of an ancient canine lineage that still exists in a relatively undiluted form and is worthy of international recognition as a distinct breed would probably not mean very much to most Panamanians.

Modern-day Cocle province is part of the cultural heartland of the Cholos, popularly defined as of mixed race, part of which is indigenous. Since the days of the pre-Columbian Coclean culture, this province has been subject to at least two great catastrophes that have left their marks on the land and its people. It was also a primary locus for the rise of a peculiar cultural nationalism that swept across the nation but has always been strongest in the rural areas and towns of the Panamanian Interior. There are opposing ripples and cross currents but one attitude that holds strong in the countryside of modern-day Cocle is that the racial pedigrees of dogs — and also of people — don’t much matter.

Who are the Cholos? There are all sorts of legends and political formulations that have served to answer the question, and now scientists are bringing DNA analysis to bear on the question. For starters DNA suggests things untold in the standard accounts of the Conquest.

The Coclean culture may have been divided into many often squabbling territories when the Spaniards arose on the isthmus and Christopher Columbus may have run into that on the coast of Veraguas. But when the Spaniards came prepared to conquer, they first dealt with a culture to the east of Cocle, with the people of a cultural and linguistic group known as the Cuevas. Today’s Guna nation — formerly more commonly styled as Kuna and known to some as San Blas, after the archipelago where much of the population of the modern comarca (semi-autonomous commonwealth) of Guna Yala lives — surely descends from the Cueva culture. Anthropologists argue about what the specific relationship was and is. The Gunas did not exist at the time when Europeans conquered Panama and the Cuevas don’t exist today.

Vasco Núñez de Balboa tried to form alliances with Cueva elements. It was Cueva guides who showed him the Pacific Ocean, and told him of the wealthy civilizations of the Andes to the south. Balboa’s successor as Spanish governor, his brother-in-law Pedro Aria D’Avila, had a different policy. He had Balboa executed and embarked on a policy of all-out war against the Cuevas. Some retreated to the wilderness, many were massacred and a lot fell prey to European diseases to which they had no immunity. The devastation of the Cueva culture was well-nigh complete and if the Catholic Church or the government of Spain have chronicles with a lot of the details, those have generally not been published. Pedro Arias D’Avila went on to found Panama City on the site of an old indigenous settlement — graves have been found there going back 1,000 years — before being transferred off to Nicaragua. The man comes down to us through history as Pedrarias the Cruel.

There is a PEPA – Kuna gene found universally among the Guna but absent among the modern-day Bugle and with only a small trace among the members of the indigenous Ngabe nation, which descends from the Coclean culture’s neighbors to the west. The Ngabe, for their part, commonly carry two distinctive genes, the LDHB – Gua and the TFD – Gna that are generally not found among the Guna or the Bugle.

DNA studies conducted by the University of Panama’s genome institute and the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute find that by racial ancestry of a sampling of the Cholo population of Cocle province showed that it was about 44 percent Native American, 38 percent European and 18 percent African. Especially in the mountains, there are traces of the PEPA – Kuna gene. The LDHB – Gua and the TFD – Gna genes are very common among Cocle’s Cholos. Other studies of mitochondrial DNA suggest that almost all of the Cholos are descended from unions between indigenous women and white men.

It’s not the beautiful story of heathens coming to Christ as may be suggested. The Spaniards massacred the men and raped the women, with remnants of the Cueva and Coclean peoples fleeing for their lives to the hinterlands to eventually become the modern-day Guna and Bugle nations. Some of the Cuevas, it seems, made their way to the mountains around Capira and El Valle to find refuge and eventually merged into what became the Cholo population.

Perhaps the accounting of the full enormity of the massacre that accompanied the Conquest is best given by ecologists, agronomists and geologists who study the soil, although the archaeologists and anthropologist will tell you the same thing. Forget the romantic notion of Panama’s original nations living close to nature as hunters, gatherers and fishers in a beautiful rainforest paradise. The Spaniards found a deforested Cocle, with lands that had been cleared thousands of years before and established communities farming on those lands. The forests grew back after the Conquest because there were few people left to work the land.

The settlers and their families still had to eat, so slaves were brought in to plant, weed and harvest the crops, tend the chickens, pigs, cattle and horses, catch the fish and gather the oysters. In the Cueva area indigenous slaves from Nicaragua, Venezuela and Peru were introduced and became part of the racial mix, while thanks to a generation of resistance led by a man named Urracá the Coclean culture hung on long enough for the Spanish slavery policy to have changed to the importation of Africans to do the work. But mostly there wasn’t a lot of work done. For centuries Cocle was a shattered remnant of the populous agricultural province that it was. High-ranking Spaniards — the hidalgos or “sons of somebody” — ran vast cattle ranches and cash crop plantations on the fertile lowlands. Only very slowly, starting first in the hills and in the more remote or less arable places, did the Cholo culture grow and start working the lands of Cocle province again.

So, a mixed-race culture? The Cholos weren’t and by and large still aren’t overly concerned about their own families’ pedigrees, let alone those of their dogs.

The hidalgos? Originally these were the younger or outside of wedlock sons of the Spanish nobility, some of them army officers who were given land grants in exchange for their services. In the early times only high-ranking officers or individuals from families with influence in the royal court were allowed to bring Spanish wives to Panama with them.

There is a white elite, the wealthy or at least pretend wealthy minority of Panama’s less than 10 percent white minority, that would claim to be descended from the hidalgos. This dominant aristocracy, popularly known as the rabiblancos, would promote their genealogy into the most important of all Panamanian subjects. But the reality of Panama since colonial times is a boom and bust economy that often had those who made a lot of money here taking their winnings and emigrating and on the other hand had once high and mighty families ruined and left with little more than illustrious surnames. Set aside the pervasive fraud in the rabiblanco family histories, and the admixture of foreigners as the product of the sons of rich white Panamanians studying abroad and coming home with foreign wives, the criminal fortunes misrepresented as old money inheritances and all the rest of the flim flam. There is a caste of Panamanians that for the most part inaccurately styles itself in terms of purity in of race or class, and those are the folks most interested in pure bred animals, including dogs. Members of this caste notoriously get swindled by North Americans and Europeans — or by each other — who sell them purported show dogs with bogus papers or with undisclosed genetic defects.

(Rabiblancos? It’s the Panamanian Spanish word for the White-tailed hawk. There are all sorts of folk tales about how a caste of Panamanians came to have that term attached to it. A common one is that way back in some remote but not too remote times, only the rich could afford toilet paper, while everyone else had to be content with leaves.)

In colonial times the isthmian economy boomed when Peru — then silver-rich Upper Peru that’s modern-day Bolivian and the golden Incan empire of Lower Peru — was being looted. The precious metals came to Panama City, were carried on the backs of mules to Nombre de Dios and later Portobelo on the Atlantic Side, and were loaded on galleons that went in convoys to Spain, often with stops in Cuba, Santo Domingo or Puerto Rico. (The similar sorts of Spanish spoken by Panamanians, Cubans, Puerto Ricands and Dominicans are sometimes referred to as the variants of Trade Routes Spanish.) The trade routes went two ways, with the galleons bringing cargoes of all sorts of merchandise from Europe, which was sold at great trade fairs at Nombre de Dios and later Portobelo. A combination of the predations of British raiders, the diminishing yields of precious metals and stones from the Andes and French merchants’ access to the markets of Spanish America made the trade fairs obsolete. The last one was held in 1731, but they had been economic failures for years before that.

Who loaded and unloaded the galleons during the boom days of the trade fairs? Who drove the mule trains across the isthmus? African slaves, who also did most of the actual construction work on the fortifications and main buildings of the trade fair epoch. (The design of a lot those structures, however, was by Italian architects.) There had always been an element of the slave population that ran off to the jungle and set up a small-scale way of life based on West African traditions — the Cimarrones. That culture got some relief and reinforcement as the end of the boom left a lot of slaves to their own devices, generally small-scale fishing or farming. Today in congo dancing and the diablo masks of Colon province, which bear a striking resemblance to African masks, one sees the remnants of the Cimarron culture.

Slavery wouldn’t formally end until the 19th century, but the trade fairs’ demise killed it off. The institution’s staying power was considerably less than in parts of the United States and the Caribbean for two main reasons. The first was that apart from sugar cane and rice for mainly local consumption, Panama didn’t have much of a rural plantation economy in which slavery could be profitable. Second was the ideology of the Catholic Church, which while it condoned slavery and had certain racist attitudes, considered slaves to be human beings rather than livestock and never forbade interracial marriage.

With the end of the trade fairs there was an exodus of the wealthy from Panama — a lot of them moved on to what is now Ecuador — and for about 120 years Panama became a sleepy provincial backwater. Were you young, rich, white and socially ambitious in those times? You might have left, seeking to join higher society than what the isthmus had in such places as Quito, Cartagena or Bogota. Political power may have derived from an ever more decrepit Spain, but it ran through a viceroy in Bogota and only later to the hinterlands among which Panama numbered.

Did the rich who left the isthmus for better pickings take their dogs with them? That would be an interesting question for historical research, for which it is hard to see grant money available for scholars who would look this up. Surely traces would remain in private letters and on ship manifests and customs documents.

The end of the trade fairs not only sent a generation or two of elitists elsewhere. It started a repopulation of the Interior and largely sounded the death knell of colonial era slavery (even if it didn’t immediately end). When the Welsh privateer Henry Morgan — call him Morgan the pirate or Sir Henry, the Lieutenant Governor of Jamaica according to your point of view — sacked the old Panama City in 1671 part of the plan was to kidnap those whose families might have the resources to pay ransoms and to add some urgency to the matter with a bit of torture. He arrived to find a largely abandoned city that had largely been destroyed by its inhabitants on orders of the Spanish governor. Whoever could fled, many of them by sea toward the west, landing on the Azuero Peninsula in what is now the province of Los Santos. The people cut up the timbers of the ships in which they fled and founded the town of Las Tablas (The Boards).

There are legends of how a community of crypto-Jewish craftsmen and merchants were among the founders of Las Tablas — it had been illegal to be Jewish in the Spanish Empire since the fall of Granada in 1492 and there was an element in Spain’s Jewish community that feigned conversion to Catholicism — but those tales have never been documented and would not have been. When the Puritan fanatic Henry Morgan came to wage holy war on Catholic Panama and do a bit of looting on the side, how many Jews would have wanted to stick around for that event? We will probably never know. Panama’s present Jewish community comes from a later time.

In any case, the refugees from the destruction of Panama Viejo became the nucleus of of a cultural heartland, developing a local dialect of Spanish and a rural and small town way of life that in many ways mixed well with that of the Cholos in neighboring Cocle province. Today when one thinks of the Central Provinces — Cocle, Los Santos, Herrera and Veraguas provinces — one thinks of Cholos, such musical traditions as Panama’s version the cumbia, fashion traditions like the pollera dresses, a cuisine that goes heavy on the culantro and the garlic and a number of other regional hallmarks.

But are rural Azuero dogs the same as rural Cocle dogs? This writer has not taken anything approaching a census and it appears that nobody else has either. It would seem that if the “little reindeer” with the very short hair and big upright ears are in the mix in the rural Azuero you will find more dogs with floppy ears and a bit longer hair as a percentage of the population.

After the flight from the old Panama City to Las Tablas, politics and warfare continued to at times bring Cocle together with the rest of the central provinces and at times differentiate them. In the declining days of Spanish rule, when Bolívar had taken Bogota and the viceroy went into exile in Panama, on November 10, 1821, the town of La Villa de Los Santos declared independence from Spain. Las Tablas and other communities in Los Santos joined in, as did Nata and Penonome in Cocle province. took until the 28th for Panama City’s leading citizens and the local Catholic hierarchy to decide that the communities of the Interior had a good idea but to make the fateful decision that independence from Spain should not be as Panama but as a part of Bolívar’s Gran Colombia. There is no record of the dogs in Panama’s rural areas taking notice, although one might presume that to the extent that there were fireworks it hurt their sensitive ears.

The marriage to Colombia turned out to be unfortunate, but some 30 years into the Colombian period new boom times came to Panama. The California Gold Rush and the construction of the Panama Railroad brought all these American fortune-seekers across Panama — with or without the trains, it was much quicker and cheaper to go by sea to Panama, cross the narrow isthmus overland and continue by sea to the US West Coast. The railroad project permanently established three new ethnic groups in Panamanian society: the Americans, the West Indians and the Chinese. These new racial facts later gave rise to a political movement whose epicenter was in Cocle and the new economic reality made Panama a more vibrant commercial center than it had been in a long time.

Panama’s unhappy experience with Colombia was 82 years of off-and-on warfare between Liberals and Conservatives. The Conservatives wanted Catholicism as the nation’s official faith while Liberals were for freedom of religion. The Liberals’ wealthy elite by and large came from the commercial, industrial and professional sectors, while the money behind the Conservatives mostly came from the large landowners. Many compromises were tried and they all broke down, often because the notables and warlords of the periphery felt no compulsion to go along with what was decided in Bogota.

Then in 1899 came The Thousand Days’ War, which the dogs of rural Cocle could not help but notice, while their counterparts in the other central provinces may not have been much affected. In Bogota the Conservatives maintained themselves in office by way of election fraud but their standard bearer, President Manuel Antonio Sanclemente, was too ill to rule. The Panamanian part of the war began in Panama City with a battle for the Calidonia Bridge. The would-be commanders of the Liberal side fell into squabbling in the face of the enemy and were slaughtered. About 500 Liberals were killed and the Conservatives held onto the city for the duration.

Much of the Liberals’ armament was rescued and sent to the Interior by sea, coming ashore at Playa Ensenada in San Carlos. The Conservative mayor intercepted the weapons but a force led by a Cholo and Liberal city council member, Victoriano Lorenzo, crushed the mayor’s force, retrieved the arms and carted them off to a guerrilla stronghold west of El Valle de Anton. From there Lorenzo and his Cholo army led a campaign down from the hills and across the countryside to eventually take Penonome and Aguadulce. It was the most vicious of civil wars among rural neighbors. Almost all rural buildings were burned down. Orchards, crops and farm animals were systematically destroyed, with one side moving to drive off their neighbors of the opposing party and the other side responding in kind. Surely some dogs did not survive the violence and others were left to wander a largely abandoned countryside from which most of the people had fled.

At the war’s end Lorenzo was betrayed and executed and within six months Panama would be a US-backed and soon to be partially US-occupied independent republic. But even when in early 1904 the first US Army medical mission arrived in Panama City one could measure the ferocity of the Thousand Days’ War. The leading cause of death in what was now the capital of the Republic of Panama was beriberi, a starvation disease and surely in part the result of catastrophic devastation of an area that had produced much of Panama City’s food.

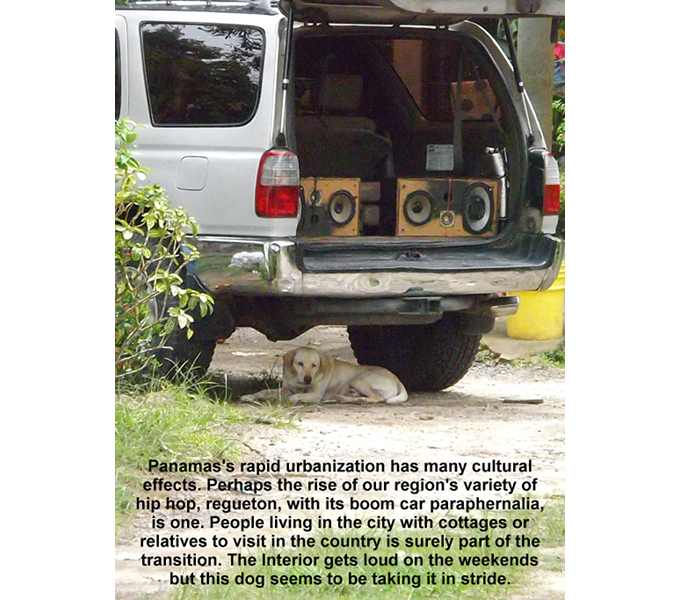

More than a century later, there is still much uncertainty about land tenure in those rural areas of Cocle where Victoriano Lorenzo’s Cholo guerrillas did battle with their Conservative foes. And the dogs? They seem to have taken it in stride.

So if Cholos and their dogs are of embracing polyglot cosmic races, is that an inspiring lesson in tolerance and universal assimilation for the world? The politics of it have often been anything but, thanks largely to two brothers from Cocle’s provincial seat, the town of Penonome.

The very name of that place is a monument to the brutality of the Conquest, or so legend has it. The name supposedly derives from “aquí penó Nomé” — here Nomé was punished — as in the execution of an indigenous leader during the course of Cocle’s subjugation by the Spaniards. And the two brothers, Harmodio and Arnulfo Arias — were they white guys or light-skinned Cholos?

Back in the 1920s the Arias brothers, Harmodio an attorney and Arnulfo a physician, were leaders of a movement called Accion Comunal. That group used to dress up in white hooded robes hardly distinguishable from those of the Ku Klux Klan and their demands were to expel everyone of Afro-Caribbean, Asian or Middle Eastern ancestry from the isthmus. Politically a splinter faction of Liberals, they were central to a January 1931 coup, then Harmodio served as president from 1932 until 1936. Arnulfo served in various government posts during his brother’s administration, then was elected president for the first time in 1940. Arnulfo was declared elected three times and denied the presidency by fraud at least once, but was never allowed to serve a complete term as president.

The Arias Madrid brothers have on their list of accomplishments the establishment of the University of Panama, creation of Panama’s Social Security Fund and women’s suffrage. In 1941 Arnulfo, who as ambassador to France and then the United Kingdom, was deeply impressed by Mussolini’s Italy and became a friend of Adolf Hitler, promulgated a new constitution that stripped all Panamanians of non-Hispanic West Indian, Asian or Middle Eastern ancestry of their citizenship. By that time ships loaded with war materiel on the US West Coast were passing through the Panama Canal, just off of the Caribbean entrance to which German U-boats were lurking. Franklin D. Roosevelt found it unacceptable to have one of Hitler’s friends as the president of Panama and thus engineered an October 1941 coup that deposed Arnulfo Arias.

Later Arnulfo Arias and his supporters denied any racial motives for the citizenship provisions of the 1941 constitution, claiming that they were a defense of the Spanish language and Panama’s national culture. The Arias brothers were light-skinned but of mixed race. In his later runs for the presidency Arnulfo would use photos and other graphic depictions that made him look a bit darker.

There is a Panamanian saying that enough money will make anyone white. In that sense the Arias brothers were white. It fits with a Latin American concept that differs markedly from the US concept, embodied in the Black Codes from the days of slavery and Jim Crow, that ancestry determines all. Thus the “one drop rule” that if a person has any African ancestry at all — even one drop of blood — she or he is black. But to Latin Americans race is much less of a matter of lineage and much more a matter of the culture that one lives. The Panamanian concept fits better into the traditional Catholic views about race, and into a legal framework that neither recognizes illegitimacy nor countenances discrimination in inheritance or otherwise based on whether or not one was born to parents who are married.

None of this is to say that the circumstances of one’s birth don’t matter in the Panamanian countryside, either for people or for dogs. There are exaggerated class divisions in Panamanian society and it very much does matter to a dog whether she or he is cared for on a rich family’s vast estate or on the hardscrabble farm of a family that doesn’t get enough to eat.

If being a dog person was not a part of Arnulfo Arias’s public persona, after his days in politics Harmodio Arias retreated to a vast cattle ranch in Cocle’s Anton district and his constant companions there were a pack of dogs. By then he was a private citizen. His relationships with and attitudes about dogs were not part of the images and messages that he put out as a public person.

In rural Cocle, where most of this chapter’s country dog photos were taken, people tend to let their dogs run. The farther one gets from the main roads, the less risk of a dog being killed in a traffic mishap. A campesino dog will be taught at a very young age not to mess with the chickens and somehow or another is likely to learn the futility of bothering cattle or horses. “Perro bravo” signs are much easier to find than an actual vicious dog — if the Spanish conquerors of long ago dismissed the dogs of the Panamanian countryside as yappy little things they still are. It’s their job.

Do these dogs run in packs? Well, in a little village like Juan Diaz de Anton, with fewer than 400 households, there are a lot of dogs and if those allowed to roam at large do wander and do congregate, they tend to socialize mainly with close neighbor dogs.

But for male dogs, a major exception to the usual daily rounds is when there is a bitch in heat. That will turn male dogs who are ordinarily friends into snarling, biting rivals. It will explode the dog population, and shorten the lives of females who bear litter after litter until they die.

What can be done to improve the lot of country dogs should seem straightforward enough. They need to be better fed. They need to be better protected against fleas, ticks and intestinal parasites. They need to be spayed or neutered. However, most of the people with whom they live scrape by close to the economic edge and get around by bus. As a practical matter that often makes the veterinary care that’s clearly called for unavailable.

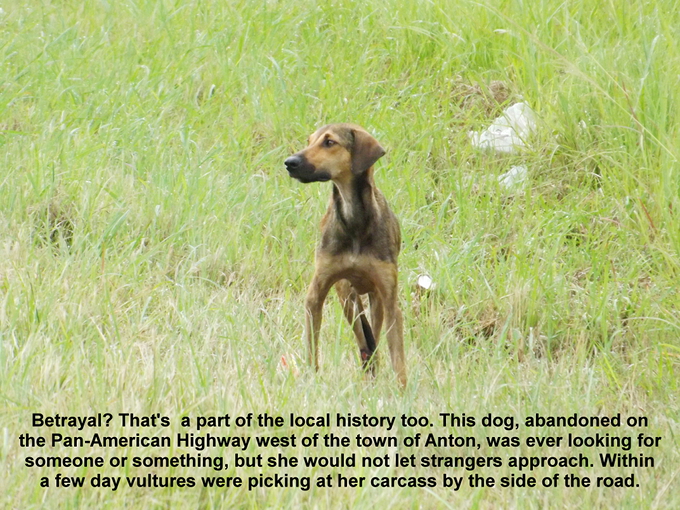

It’s a sad state of affairs, but not nearly so bad as to break the ancient alliance between people and dogs. And if you say that this chapter has hardly been about dogs, but rather is about people and slices of their history, consider what it all says. Out in the countryside people and dogs have shared a community for thousands of years, surviving wars, plagues, famines, dispossessions, persecutions, genocides, betrayals, abandonments and fights over who stands where in the pecking order. There is a lot of room for improvement, but it has been a long and successful run.