Martinelli loses on a key motion

by Eric Jackson

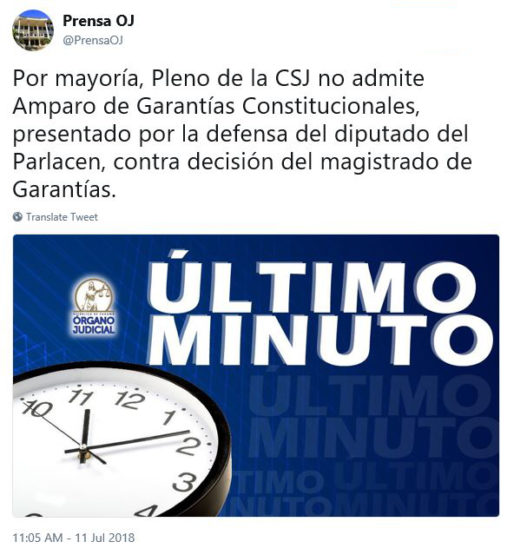

Whether he was malingering again or actually had symptoms that needed to be looked at in a hospital, Ricardo Martinelli was in Santo Tomas Hospital rather than at the courthouse to put on his show. The nine magistrates and suplentes who made up the panel didn’t go before television cameras to make their announcements, nor did they immediately publish their various supporting or dissenting opinions. It was just a tweet on the courts’ seldom-used Twitter feed. They didn’t refer to the defendant / appellant by name — just as “the PARLACEN deputy,” the denial of which status was the crux of former president Martinelli’s claim. They didn’t say who voted which way and why — just “by majority,” which means not unanimously. They didn’t specify WHICH petition to vindicate constitutional guarantees — everybody who has been watching and knows the basics of Panamanian law knows which one.

Ricardo Martinelli resigned his seat in the Central American Parliament (PARLACEN), the possession of which put his case before the Supreme Court instead of the ordinary courts in the first place, after his trial was underway. It was a letter crudely and unacceptably written (as far as PARLACEN was concerned) in his jail cell in Miami when he was fighting extradition, then submitted like an ace pulled out of a sleeve once he was back in Panama and proceedings were underway.

Magistrate Jerónimo Mejía, acting as judge in that case, rejected the ploy. “You can’t let the will of one person distort the system,” Mejía said. “From this point there are substantial limits on this attempt, such as due process, reasonably timely justice and the rights of the victim, which deter the court from losing jurisdiction.” Martinelli’s phalanx of lawyers appealed and on Wednesday, July 11 a nine-judge panel denied his motion to vindicate claimed constitutional guarantees.

This case, the one about illegal eavesdropping and theft of the use of the equipment with which that was done and of the equipment itself, is not over. There are a number of other criminal cases pending against Martinelli, some of which have progressed in pretrial stages in the Supreme Court, some of which are not that far. Very likely those are to be devolved to the ordinary courts and prosecutors. In the current case at hand, the nine-judge panel looks today (Thursday, July 12) at two more Martinelli motions. One is an appeal of Judge Mejía’s refusal to recuse himself from the case and the other is a claim that since the National Assemby received complaints about Martinelli’s eavesdropping back in 2011 but dismissed them without any investigation or hearing it’s double jeopardy for him to be tried on these charges now.

It’s never quite possible to accurately predict what the Panamanian Supreme Court will do next, but today’s motions are frivolous and unlikely to prosper.

Is the argument that Mejía won’t do what Ricky Martinelli tells him to do and since the world revolves around Ricky that’s an aberration that must be removed to set the world back in proper motion? Pardon the diminutive, but here we have the spectacle of a former president acting like a toddler.

Is it a more mathematical calculation, that Mejia is one of two magistrates who were appointed by Martín Torrijos, whose terms should have ended this past New Year’s Eve but didn’t because President Varela’s nominees could not get confirmed? Eliminate two Torrijos appointees, don’t add two Varela replacements, that theoretically gives Martinelli appointees a bigger edge among the entire court membership and the former president might think enhances his possibilities of acquittal. Shall we talk about the quality of purchased loyalties? Shall we talk of judges taking account of political winds? Shall we talk about ordinary and well nigh universal standards of judicial ethics? Without getting into any of that disrespectful talk, the constitutions says that magistrates remain in office until their replacements are confirmed.

The plenum might let Martinelli walk on today’s motions, or the panel of magistrates serving as the jury might acquit Martinelli on the charges at hand. If they don’t, the magistrate acting as prosecutor, Martinelli appointee Harry Díaz, is asking for a 21-year prison sentence. Presuming conviction, that might seem a bit extreme — or maybe not, considering that some of the people whose privacy Martinelli invaded were judges — and they might hand down a lesser sentence.

It does appear, however, that the rejection of Martinelli’s motion on jurisdiction cooks his legal goose. The fact that this setback did not bring a crowd of Martinelistas onto the streets to protest probably also means that the ex-president’s political relevance has passed.