Adolf and Amin

by Uri Avnery — Gush Shalom

Binyamin Netanyahu is a perfect diplomat, a clever politician, a talented leader of the army.

Lately, another jewel has been added to his crown: he is also a gifted story-teller.

He has provided an answer to a question that has perplexed historians for a long time: When and how did Adolf Hitler decide to exterminate the Jews?

There was no agreed-upon answer. There were those who thought that it happened already in his youth in Vienna, others guessed that it happened after World War I in Munich, or when he wrote his book Mein Kampf in Landsberg prison in 1924.

Now Bibi has uncovered the circumstances, the exact place and time.

It happened in Berlin, when Adolf Hitler met the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Haj Muhammad Amin al-Husseini, on November 28, 1941.

Netanyahu has not condescended to tell us how he arrived at this revolutionary discovery. There is no indication in the official protocol of the Hitler-Husseini meeting which was prepared by the Germans, in their famous exactitude. Nor is it mentioned in the entry of the Mufti himself in his private diary, which was captured by Western intelligence. The two documents are almost identical.

So what did Netanyahu discover?

According to his story, until the meeting Hitler did not even think about exterminating the Jews, but only about their expulsion from Europe, preferably to Madagascar, then a French colony. But then came the Mufti and told him something like “if you expel them they will come to Palestine. Better kill them all in Europe.”

“What a wonderful idea!” Hitler must have answered, “Why did I not think of that myself?”

A thrilling story. The trouble is that it contains not one word of truth. In the jargon of these Trumpian days, it is “alternative truth.” Or, simply put, a complete lie.

Worse, it could not have happened.

Anyone who has a minimal knowledge of the period, of the “spirit of the time” and of the personalities involved, must know that this is an imagined event.

Let’s start with the main hero: Adolf Hitler.

Hitler had a solid “Weltanschauung” (world view). He acquired it in his youth — it is not clear exactly when and where. It was called “anti-Semitism.”

Note: “anti-Semitism,” not “anti-Judaism.”

The difference is significant. Anti-Semitism was part of the Race Theory, which claimed to be an exact science and was at the time at the height of its world-wide popularity.

This was not just an ideological fad, an invention of demagogues. It was a branch of science that was assumed to be as objective as, say, mathematics or geography. The basic assumption was that every race of human being, like every breed of horses or dogs, has specific characteristics, good and bad.

This “science” was taught at universities, respected professors conducted experiments, measured skulls and analyzed body-build, It was all very serious. Quite a number of Jews were devotees. Such as, for example, Arthur Ruppin, who later became a leading figure in the Zionist settlement organization in Palestine.

According to the German race theory, there is a master race, the Aryan, which originated in India and from which the Germans are descended, and there are inferior races, the “Semites” and “Slavs” for example. According to the race theorists, this is not a matter of opinion. It is solid scientific fact, a fact that cannot be changed.

Hitler believed in all this nonsense, as a pious Jew believes in the scriptures. The Mufti was a Semite. Not one of those upright princes of the desert described in the stories of the No. 1 German author of children’s books, Karl May (who mainly wrote about American Indian chieftains), but a wily, shifty politician, who was not very prepossessing.

Hitler did not like him at all. He did not want to receive him, but his propaganda people insisted. In the end, he received him, talked with him for an hour and a half, had a picture taken and never agreed to meet him again.

It was definitely not the beginning of a beautiful friendship.

At the meeting, two translators were present. The Mufti spoke French — a language he had learned as a boy, when for a time he was a pupil of the French-Jewish “Alliance” school. The Mufti had also been a student at Cairo’s al-Azhar, the famous religious university, but never finished his studies there.

The Husseini clan is the most distinguished in Jerusalem. Nowadays, it numbers about 5000 members. One of my best friends was Faisal al-Husseini, a wonderful person with whom I organized several demonstrations against the occupation and for peace.

For many generations, scions of the family held the position of Mufti — the highest religious authority in the city, the third holiest in Islam. Before him, both his father and half-brother had been Mufti. Amin himself made the pilgrimage to Mecca already as a boy. Hence the title Haj.

Haj Amin was a natural leader. From an early age he was famous as an Arab nationalist and political activist. During World War I he was an officer in the Ottoman army, but saw no combat and deserted. Then he was active in the Arab rebellion of the Sherif of Mecca (with “Lawrence of Arabia”), and agitated for a united state of Syria, Palestine and Iraq.

Very early on he saw the danger of the Zionist settlement in Palestine and called for resistance. After Palestine became British, the Mufti organized the armed clashes of 1921, which can well be considered as the mother of the war that is still going on.

On the Jewish side of that event, the outstanding personality was Vladimir (Zeev) Jabotinsky, the spiritual father of today’s Likud, who prophesied that Arab resistance to the Zionist project would never end: no indigenous people has ever peacefully accepted a colonialist enterprise. (His answer was to build a Zionist “Iron Wall”).

Yielding to local pressure, the first British High Commissioner of Palestine, the Jew Herbert Samuel, appointed the rebellious young leader as the Mufti of Jerusalem, hoping to quieten him down. He was to be disappointed. After organizing several rounds of “disturbances,” the Mufti called for the “Great Rebellion” of 1936 against the British and the Zionists, which developed into a major campaign with many casualties.

The Mufti had to flee, first to Lebanon, then to Iraq. When the British were preparing to enter Baghdad, he fled to Italy, met Benito Mussolini and broadcast to the Arab world. He was asked to come to Germany and help a propaganda campaign to win over the Arab world. It was then that he met Hitler.

The Mufti had prepared in advance a statement that he hoped Hitler would sign. It was an ambitious plan for a United Republic of Palestine[,] Syria and Iraq under German protection, and the appointment of the Mufti as leader of the Arab world.

Hitler glanced at the paper and put it aside. He refused to consider it. First of all, Vichy France was a German ally, and Hitler would not hint that the French colonies would be taken from France. He also did not like the mufti.

All he promised was that after the German army reached the South Caucasus, he would make such an announcement. At the time, the Wehrmacht was at the northern gates of the Caucasus, a long way from the south. It never got there.

In the conversation, the Jews did not come up at all, except for a mention by the Mufti of “the British, Jews and Bolsheviks” as the enemy, and a vague remark from Hitler that the “Jewish question” must be solved “step by step.”

The meeting was photographed, as was a later meeting of the Mufti with Muslim volunteers of the Waffen-SS. All in all, the Mufti played a minor role in the German propaganda effort aimed at the Arab world.

All the rest is the fruit of the vivid imagination of Binyamin Netanyahu — who was born eight years after the event.

~ ~ ~

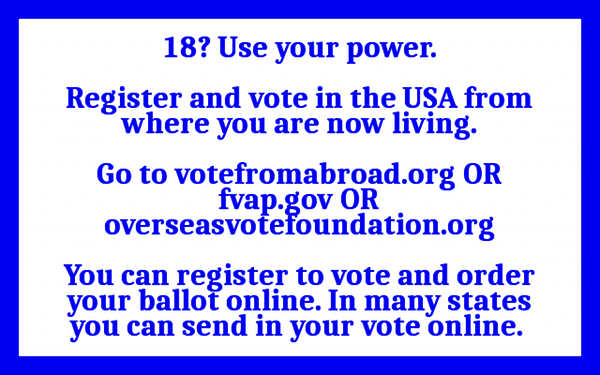

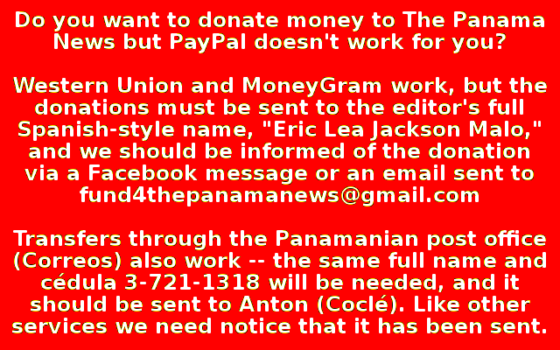

These announcements are interactive. Click on them for more information.